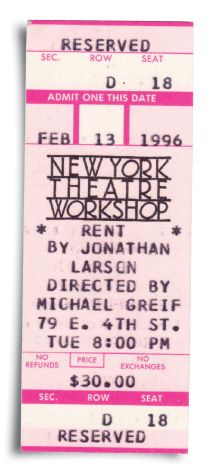

When Rent began rehearsals in December 1995, it hardly looked like a phenomenon in the making. Composer Jonathan Larson had only recently quit his job at a Soho diner, its stars for the most part had little theatrical experience, and Broadway was dominated by long-running British-import megamusicals like Les Misérables, The Phantom of the Opera, and Miss Saigon.

Yet between its Off Broadway opening and Broadway debut in late April 1996, Rent generated a buzz rarely seen in theater and not truly replicated until Hamilton.

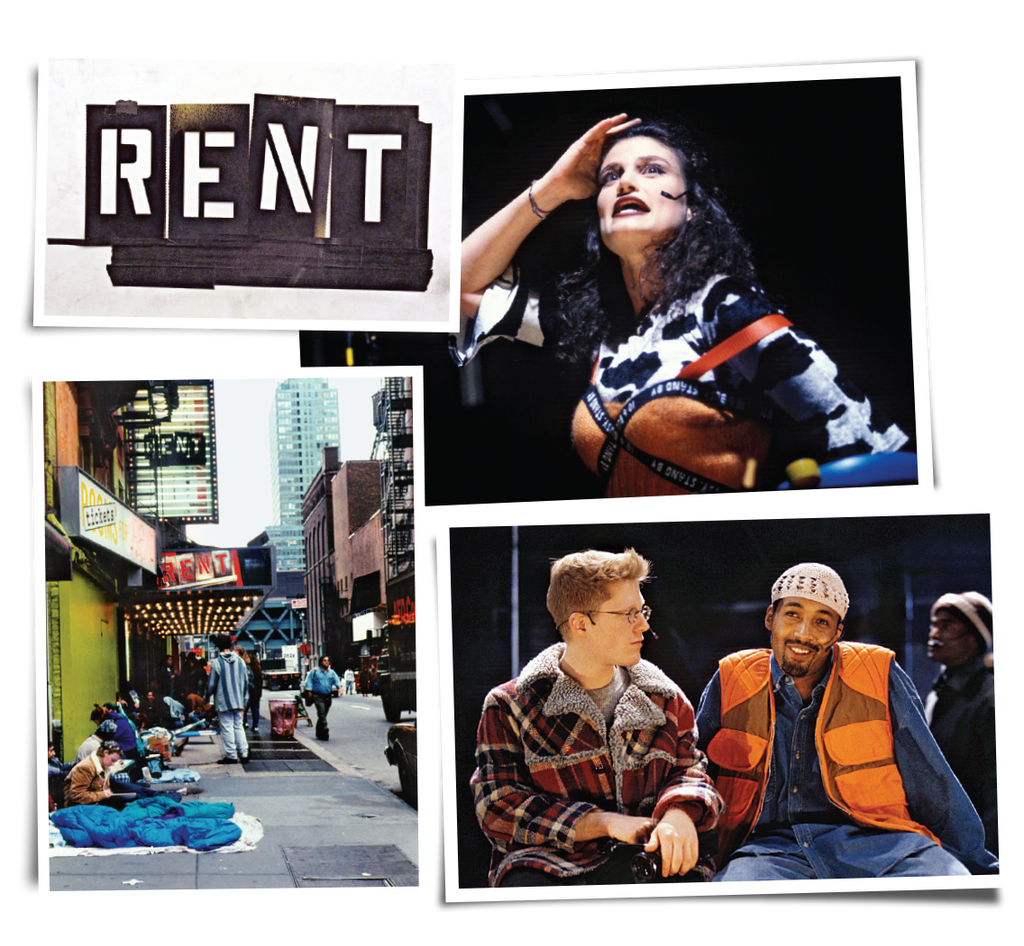

Unexpected tragedy accompanied Rent to the Nederlander Theatre; Larson died suddenly from an aortic aneurysm the night before Off Broadway previews were to begin. He was only 35-years-old. But though Larson wouldn’t see the rave reviews for his show, they confirmed his belief that Rent was going to revolutionize the musical theater of its era. The story of a group of East Village bohemians determined — against the forces of HIV, drug addiction, and gentrification — to maintain their “No day but today” philosophy was one that a generation of audiences had been waiting to hear.

Today, it’s impossible to imagine contemporary musical theater without Rent’s influence, but as with any new musical, its evolution was far from smooth. Here, the cast of characters who brought Rent to life recall the winding path that led to Broadway history.

I. A playwright and composer find inspiration.

Julie Larson (Jonathan Larson’s sister): Jonathan lived at 508 Greenwich Street in this fifth-floor walk-up; when you look at the Rent set, that’s what it was like.

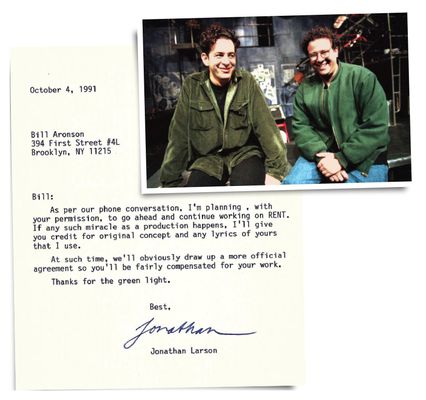

Billy Aronson (co-creator and playwright): I came to New York in the early ’80s, lived in Hell’s Kitchen, but I also used to go to the Met Opera and saw La Bohème. Walking home felt so different after seeing that opera. It’s about people who are going through similar things as me, burning their scripts for heat. I was begging people to do my plays. I thought it would be cool to do something with the Bohème story. I went to Playwrights Horizons, a theater that was doing readings of my shows, and they recommended working with Jonathan Larson. He loved the idea right away. He said, “This could be our generation’s Hair.”

Julie Larson: He’d had big disappointments. He spent years on his musical Superbia, which won the Richard Rodgers grant and was never fully produced.

Jonathan Larson [from Larson’s papers, quoted in the book The Playwright’s Muse, edited by Joan Herrington (Routledge)]: I think ultimately my work can make a lot of money and I’m not afraid of that. But I’m not interested in using my talents strictly to make a buck. My primary goal is, with integrity and class, to fulfill my artistic talents.

Aronson: I’d write lyrics and he’d write music. The trouble was, neither of us had collaborated before. Collaborating on a musical is harder than marriage. The first try he said was “too Thirtysomething.” The next draft I did was angrier. The song “Rent” had really angry lyrics. When Jonathan was ready, he called me over. He had this Casio keyboard, and as he started playing, I’m thinking, What am I going to say when this is over so I don’t hurt his feelings? But “Santa Fe” was cool, and so was “I Should Tell You.”

Jeffrey Seller (producer): A friend invited me to see a rock monologue on the Upper West Side called Boho Days. This lanky guy came out and sang about wondering if he’s ever going to realize his dreams, that no one’s interested in his music, and he’s contemplating whether he should sell out and get a job writing advertising copy on Madison Avenue. It was Jonathan. I wrote him a letter the next day saying, “I want to produce your next musical — any musical.” Shortly thereafter, he told me about this idea to make a La Bohème in the East Village where tuberculosis is replaced by AIDS.

Aronson: So we took an outline of the show to theaters. And they said, “These are great songs, but what will you do with them?” I didn’t know how to tell the story to his music, and we both didn’t want to spend a lot of time on a thing that seemed to be going nowhere. [Jonathan] had me sign something saying if the show ever made money, I’d get an “original content and additional lyrics” credit. I never thought I’d see it in a program.

II. A theater agrees to workshop the show.

Jim Nicola (artistic director of New York Theatre Workshop): It was the summer of 1992, and we were moving into a theater on East 4th Street. Jonathan rode by on his bike with a draft of Rent. He knew our production manager, and we decided to do a reading.

Seller: I attended the first-ever reading of Rent with two colleagues, one of whom was rich, and I thought maybe he’d invest. He left at intermission. The other guy waited till the end to say, “This will never work.”

Jonathan Larson [from a grant application in The Playwright’s Muse]: My goal as a lyricist-composer is to take the best aspects of traditional American musicals — well-made plot, three-dimensional characters, sense of humor, and integrated choreography — and combine them with current themes, aesthetics and music. I believe theatre should (and could) again be a source of pop music, which would attract a new audience.

Michael Greif (director): Jonathan was really getting at contemporary music, putting the right sounds in the right characters’ mouths.

Kevin McCollum (producer): The theater put on a two-week workshop, and Jeffrey brought me. I remember we each had a slice on the corner by the subway, and then we went over, and I just knew it was called Rent. For the first 20 minutes, I thought, I don’t know what’s going on, but there’s great energy. Then 25 minutes in, “Light My Candle” happens.

Nicola: When I heard “Light My Candle,” I clicked into Jonathan’s gifts. It was not only a great pop song, but a real theatrical scene: It had a beginning, middle, and end, and the characters were different at the end than at the beginning. That’s not so easy to find in aspiring composers, and Jonathan had it innately.

Greif: The show’s examination of how you live your life when you’re confronted with your own mortality was meaningful to me coming out of the AIDS plays of the late ’80s–early ’90s.

McCollum: I turned to Jeffrey and said, “That’s the best piece of musical-theater storytelling I’ve seen in a long time.” At the end of Act One, I went up to Jonathan and took out my checkbook. He was like, “Well, do you want to see the second act?”

Jonathan Larson [From a pitch letter in The Playwright’s Muse]: I write for the twenty-to-forty-year-old audience. People who don’t usually attend musicals yet spend money on Eric Bogosian or the Rolling Stones. I’ve studied the traditional form … but grew up listening to Springsteen, Paul Simon, and the Who, and my music reflects that.

Nicola: There’s a good chunk of time when [Jonathan and I] were at odds. I had said Jonathan should think about bringing someone in to work on the book. He didn’t want to hear that. At every performance, people could fill out response forms. There were some people who had a negative response, which was pretty consistent: Why should I care about these kids? Why don’t they get a job?

Tim Weil (musical supervisor): I began my experience with Rent as the audition pianist for the workshop. New York Theatre Workshop had an alphabetical list of audition pianists. It was 1992, so they were paying like $7 an hour. The person who called me said, “Well, no one else called us back, we got you on the phone, so come on down.”

Anthony Rapp (Mark Cohen): I’d auditioned for Michael earlier that year, and even though I didn’t get the part, it was a good experience. So I was happy when I got the audition for that ’94 workshop [to play optimistic filmmaker Cohen]. It was only three weeks of work; it didn’t seem like a life-changer.

Nicola: Anthony, I remember thinking it was such a convergence of character and actor. It didn’t feel like acting — it felt like, this is who Anthony is.

Daphne Rubin-Vega (Mimi Marquez): I had been in a girl group and we’d made a couple albums and toured, and I paid the rent with that, and then after two years I was working at Patricia Field selling makeup, copping the styles. My erstwhile evening job was working with this Latino comedy troupe called El Barrio USA. And my purple beeper went off one day. My agent said there’s this role — it’s a rock opera and the character is a junkie stripper with HIV.

Nicola: Jonathan initially felt she wasn’t as strong a singer as he’d imagined for the role. He was in favor of an actress who had an almost operetta kind of voice. Michael and I were like, “[Daphne’s] is not opera singing, but she makes these songs come alive.”

Rubin-Vega: I spoke to Jonathan and said, “What do I need to do to get this role?” He said, “Just relax. And make me cry.”

Greif: Daphne helped set the tone for how authentic we wanted these people to be. We wanted to continue to find Daphnes, and in many happy instances we did. If someone came in and showed us they were a vital, interesting, potentially authentic inhabitant of this world, that was way more important than their experience.

Nicola: The resources to produce something of that scale, it just wasn’t something we were capable of at the time. We made a presentation to the board to help us find $100,000 more, but I failed to persuade them. I realize now that when you’re making that kind of ask, you can’t be hedging your bets. You can’t say, “I think it’s going to be really good.” But I didn’t have it in me to say, “Get in on the ground floor! This is gonna be the best thing ever!”

McCollum: We asked Jim, what do you need for a full production? He and the board thought it would take $150,000 more than they had, but I figured I could scrape together $75,000. We called [producer] Allan Gordon and told him to come see the show. I figured, if he loves it, then I’ve gotten all the audience I need. And he loved it, so we met with Jim and I said, okay, we can give you $150,000. We wanted to acquire the commercial rights so we had an option if we wanted to move it. I figured maybe we’d license it, maybe it was Off Broadway.

Jonathan Larson [From an interview collected in The Playwright’s Muse]: The expenses just quadruple doing a musical … It’s gotten to a point where the American musical is sort of an endangered species because it’s such a gamble to produce. If you’re young and just starting out writing a musical, it’s almost impossible to break in.

Rapp: There was no reason to think it would become mainstream in any way.

Lynn Thomson (dramaturg): I was hired in the spring of ’95 to help develop the book. I suggested setting the current draft aside and starting with basic questions about the story. That was the issue: There was no story.

Nicola: We insisted Jonathan work with a dramaturg. We said [to Jonathan], “Show us something by July 1.” We got to July 1, and he didn’t have much. But by September, the first act was in good shape.

III. The show’s ensemble is filled out with a cast of relative unknowns.

Nicola: From the very first reading, we decided it couldn’t be an all-white group, because that wasn’t the East Village.

Bernie Telsey (casting director): I didn’t know it would be the hardest thing ever to cast. You go to meetings and hear, “We don’t want a traditional musical-theater voice, we want a rock voice,” but it wasn’t like today, where half the musicals are some sort of rock or pop musical. For an actor, there was no business reason to do it — it was a $300-a-week paycheck. Where was I going to find these people? It was like being a detective. Like, “Okay, I don’t know who Idina Menzel is; she sings at bar mitzvahs, but I’ll try her.”

Wilson Jermaine Heredia (Angel Schunard): Drag was not something I’d done before, but the lifestyle was very familiar to me; I’d been a club kid. I went into my audition in overalls, combat boots, and a goatee. I figured, I’m not changing for an audition. I’d done a couple Off Broadway shows, but at that point I was working the graveyard shift at the complaint center for a property management company, and my health insurance had just kicked in. Even after I got the part, I was debating taking it because it was a limited engagement, and what about my health insurance?

Don Summa (press agent): There weren’t really musicals written about people who are gay and in interracial relationships. But Michael Greif’s direction never underlined that there was a black woman and white woman singing a love duet [“Take Me or Leave Me”], or that there was a black guy, Collins, with Angel, his gay Latina drag-queen boyfriend — it just was.

Telsey: [Activist-professor] Tom Collins was written as a Bruce Springsteen type, which I’d call a white guy. But after not finding that, someone said, “What if we start seeing a Marvin Gaye–type Collins?”

Jesse L. Martin (Tom Collins): Bernie called and said, “There’s a musical being developed by New York Theatre Workshop — you should audition.” He sent me a cassette with Jonathan singing. I don’t mean this as a dis, but he sounded like Kermit the Frog. I was like, “I don’t know about this.” It wasn’t a great fit for me on paper.

Telsey: Jesse was like, “I don’t do musicals.” I kept saying, “This is nontraditional, it’s not about ‘Sing out, Louise!’ ”

Martin: I walked in and sang “Amazing Grace.”

Telsey: They cast him on the spot.

Idina Menzel (Maureen Johnson): I was singing at weddings, playing gigs at the Bitter End, begging friends to come. January and February are the slowest wedding months, so I auditioned hoping to … pay my rent.

Telsey: I remember Idina came in to the audition with this leather-patchwork miniskirt, all different colors. And she had the killer voice.

Greif: I had seen Idina in an audition a year earlier, and I’d written a note to myself: “Not exactly right for this, but she’ll be great as Maureen [a lesbian performance artist].” She had that sexuality and innocence and kookiness.

Adam Pascal (Roger Davis): I’d just broken up with the band I’d been playing in. Idina and I grew up together, and she dated a friend of mine. He told me she’d been cast in this rock musical and they were having trouble casting the role of an HIV-positive rock singer. So on a lark I auditioned.

Telsey: Fifty guys showed up; 49 of them looked like Alice Cooper, and there’s this one good-looking guy. It was like, Please, God, can a guy this handsome sing?

Pascal: Michael said, “We like you for this part, but you sing with your eyes closed. Sing ‘Your Eyes’ to Bernie with your eyes open.” So I sang it to him as if he was dying Mimi. They wanted to see if I could act.

Tim Weil (musical supervisor): So much of the role of Benny [an opportunistic landlord] depended on Taye being Taye. He’s charming, with attitude.

Taye Diggs (Benjamin “Benny” Coffin III): I skipped the first two audition requests. The first time I called in sick, the second time I said I didn’t want to do it, and then the third time I half-assed it to get my agent off my back. I was trying to do TV and film. At the audition, I sang something from Jesus Christ Superstar.

Greif: We were all looking for ways in which Benny was not the villain and in fact represented a credible point of view, even if he had to do some shitty things.

Diggs: I saw my character as the one with the least lines. It wasn’t until I had a conversation with Michael — he made me feel like I was just as important as the others.

Martin: Everyone had an interesting quality. Daphne sounded like this tragic little bird, and then she’d burst into an angsty growl. Idina, that girl opened her mouth to sing, I was like, Whoa, where did you come from?

Pascal: Daphne was this little firecracker of sexiness. I couldn’t wait to come to work to be around her.

Rubin-Vega: Adam was adorable. And when we had to kiss, he actually kissed me!

Diggs: I had my eye on all the girls. Idina and Daphne, they were the most shapely and dynamic.

Pascal: I didn’t have any gay friends. I didn’t know anyone who was HIV-positive. All my friends were white. And now I had this new multiethnic and multisexual group of friends.

Greif: Starting out rehearsals with “Seasons of Love” was Tim Weil’s wonderful idea. We began with those large numbers to be sure everyone felt they were an important part of this musical and there wasn’t a hierarchy of who mattered and who didn’t.

Martin: Somewhere during the first week of rehearsal, Jonathan came and he had these ratty Converse All-Stars, and I remembered seeing those shoes at the Moondance Diner where he worked. Before Rent, I’d waited tables there, and Jonathan trained me. I was like, “Dude, now I know where we met!”

Greif: In the ’94 workshop, there was another song at Angel’s memorial service — a very beautiful song a woman from the ensemble sang. And one of the first conversations Jonathan and I had with Tim’s participation was, what would the extraordinary pay-off be if Collins sang that song instead? It was very exciting to be there the moment the notion of the “I’ll Cover You: Reprise” was born.

Martin: I was always struggling with the “Reprise.” I’d go home and try my damnedest to open up my voice and just let the song come out, but it wasn’t coming. I remember Michael telling me, “You need to sing the shit out of this song.”

Greif: A lot of it was: “Take control.”

Martin: I remember grabbing myself by the balls and saying, “Just sing it, just let it out.” I had to go to a gospel place.

Rapp: Between ’94 and ’95 Jonathan wrote “Halloween” and “What You Own,” which hadn’t existed in the earlier workshop. He told me he wrote them with my voice in mind.

Heredia: My character Angel’s voice is something we developed out of “I’ll Cover You.” Tim initially said, why don’t you sing like Stevie Wonder? Eventually Angel’s voice became that.

Martin: Wilson and I decided that we didn’t want to be cartoonish or stereotypical. And it took a lot of work to get there. I’ll never forget the first time I saw him put on those heels. He seemed so comfortable just walkin’ around; I was like, “Have you done this before?” “No, but I’m gonna look like I’ve done it before.”

Heredia: During that time, portrayals of LGBT characters were more like comedy relief, and I didn’t want Angel or the relationship to be that. Jesse has such a warm personality — you look into his eyes and even if you’re straight, you’d fall in love. I trusted him wholeheartedly — that made it easy.

Pascal: A lot of directors could have been frustrated or condescending with a guy like me, but Michael never made me feel like the inexperienced one. That made a huge difference in my confidence.

Julie Larson: I love “Will I?” Jon’s closest childhood friend was HIV-positive and he started going to this AIDS support group, Friends in Deed, to support him. At one meeting this gentleman said, “I’m not afraid of dying, but will I lose my dignity?” That’s where that song came from.

Rapp: “La Vie Bohème” — there were things in that song I’d never heard a musical talk about. “To faggots, lezzies, dykes, cross-dressers too”; “to people living with not dying from disease.” That was shocking, a jolt of reality.

Thomson: “Rent” was initially a complaint. Jonathan always wanted the word rent to have a dual meaning — it was about being torn apart, as well as paying rent.

Nicola: Some of the best stuff in the piece came late. “What You Own” was very late. “Take Me Or Leave Me” arose in the first week of rehearsal.

Weil: There was this slot in Act Two for Maureen and Joanne to have that song, and [Jonathan] was trying to write something funny. He came in one day with this rock waltz, and Michael said to him very nicely, “I think you have to go back to the drawing board.”

Greif: Between the end of ’94 and winter ’95 Jonathan probably wrote three or four duets for them, and couldn’t quite land them.

Larson: Jonathan kept saying he felt like he had to better get to know Idina and Fredi [Walker, who played the role of lawyer and Maureen’s love interest Joanne Jefferson]. I remember in the middle of the day he called me and said, “Listen, I got it,” and then he had to run to play the song, and he called back and said, “They loved me,” and that song was “Take Me Or Leave Me.” I have strong memories of how excited he was to have finally found the voice for them.

Thomson: There were things that weren’t finished. The whole performance-art piece [that the character of Maureen does] was unwritten when rehearsals started because Jonathan wanted to improvise it with Idina. Which he did, and I was at that rehearsal. Idina was very inexperienced, and she should get more credit for her improvising.

Menzel: Michael told me that Maureen “is a woman who has studied performance artists like Laurie Anderson and Diamanda Galas but has yet to find her own voice, so she mimics them.” That was enlightening for [her approach to the character].

Weil: At one point, I invited a director friend, and I said, “It’s a mess, but Jonathan’s got an original voice.” He came and after the first act said, “Don’t you ever quit this gig. You’re doing A Chorus Line.”

IV. Hours after Rent’s dress rehearsal ends, Larson unexpectedly dies.

Nicola: There were all kinds of technical mess-ups in the dress rehearsal, but you could feel something there.

Rapp: My friends were jumping out of their skin to say how great it was. My agent was practically shaking. After the show, Jonathan was surrounded by strangers who wanted to meet him. Then someone told me he was in the box office doing an interview with the Times.

Anthony Tommasini (New York Times critic): I was told about this musical opening that was an updating of La Bohème, and it happened to be the 100th anniversary of the premiere of La Bohème in Turin. So I thought, I’ll go to the dress rehearsal. I sat there thinking, This is quite a piece. He was pulling all these sounds — rock and grunge and gospel — into this tradition. After the show, Jonathan and I talked — the only place we could find was the ticket booth.

Rapp: Jonathan was no dummy. He knew what it could mean to be talking to the Times.

Tommasini: He talked about his ambition, how it bothered him that pop and show music got divorced. But then he talked personally too — how he’d been a waiter for ten years, that he’d finally been able to quit his job, and that one of the messages of Rent was that it’s not how long you’re here, it’s what you do while you’re here.

Julie Larson: Jon had gone to two different emergency rooms within those last four days before dress rehearsal.

From the New York Times: “Twice doctors failed to diagnose the potentially treatable condition [an aortic aneurysm] that killed him, a four-month investigation by the State Health Department has found. At Cabrini Medical Center, doctors said he had food poisoning. At St. Vincent’s Hospital and Medical Center, doctors said he had a virus. Both hospitals sent him home.”

Rapp: I thought about knocking on the glass of the box office to wave good-bye to Jonathan, but I thought, I don’t want to interrupt.

Nicola: At 8 a.m. the morning of the first preview, my phone rang. It was our production manager saying his body had been found in his apartment.

Martin: I was freaked out when Jim called. The insecure actor in me said, “I’m getting fired.” He said, “Jesse, we lost Jonathan.” No part of me heard that Jonathan had died. I thought maybe Jonathan quit.

Aronson: It didn’t make sense.

Diggs: I didn’t feel like I had the right to go to his funeral. I didn’t really know him. Much later, I felt guilty and wished I had gone.

Nicola: We proposed canceling the preview. But the cast felt Jonathan would want the show to go on. So we compromised that we’d sit on the stage and sing it through, and we could all bring our friends and family.

Larson: My parents were like, “Absolutely, the show must go on.” But it was torture.

Martin: Everything changed that night when we got to “La Vie Bohème.” God bless brave Anthony Rapp, because he stood up to sing and we were like, “Wow, Anthony’s really going for it.” We all decided, well, let’s do this.

Rapp: The Act Two funeral — I don’t know how Jesse did it. He never wavered. Just from a technical standpoint, when you’re singing your throat kinda has to be open, and when you’re crying it closes up.

Martin: I held the last note so long I almost passed out. Adam Pascal literally held me up. Honestly, it was then that I learned how Collins sings that song. I hate that it was Jonathan’s death that got me there, but it did get me there.

Grief: The preview became this joyous wake to Jonathan.

V. Off Broadway previews begin January 26, 1996. Three months later, it opens on Broadway.

Weil: After Jonathan passed, we sat down and started figuring out the kinds of things we were interested in cutting. There was a lot of excess fat. I’m sure, had Jonathan been alive during that preview period, we would have made similar cuts. Maybe Jonathan would have rewritten “Your Eyes.”

Pascal: “Your Eyes” is, in my opinion, an unfinished song. I was always a little disappointed that this song Roger is struggling to write throughout the entire show, to leave as his legacy, turns out to be this song. It seemed like kind of a letdown.

Larson: All shows open being a little unfinished; that’s why they have previews, to suss out what works and what doesn’t.

Nicola: The morning after the opening night at the Workshop, we read the reviews. The response was stunning.

Summa: I couldn’t handle all the press requests and calls.

Pascal: I questioned at first, are people reacting to the show itself or the sadness of the situation and the irony of these lyrics now that Jonathan’s dead?

Rapp: The celebrities started coming downtown. The first people we got to meet and hang out with a little bit were Danny DeVito and Rhea Perlman. It was her birthday, so we sang “Happy Birthday.” We couldn’t believe a famous person wanted to see our little show.

Greif: I thought if we extended the run, wouldn’t it be great to move into some old Yiddish theater downtown?

Seller: It seemed as if every adult was afraid the Broadway audience wouldn’t embrace a musical this iconoclastic. So to Kevin and I, it became a mission: We must go to Broadway!

Larson: When the show was moving to the Nederlander Theatre, half his friends said Jonathan would have hated it and half said, “Oh my God, he’d love it.”

Telsey: All of a sudden, Rent was an industry: We need understudies? What the hell?! When we had our first open call for understudies, 4,000 people showed up.

McCollum: The first day of sales was $750,000. Now that’s nothing, but back then, there wasn’t the technology, you had to actually show up and buy tickets.

Tommasini: At the Workshop the show was both a tribute and a demonstration—look at what this guy did, look at what we’ve done, this show is great and we believe in it. On Broadway, it was the triumph of proof. We were right, he was right, and here we are. See?

Seller: This was an era when Broadway was completely dominated by British musicals: Cats, Les Misérables, The Phantom of the Opera, Miss Saigon. Jonathan was very critical of those shows: “Those aren’t my people, that’s not my music.”

Summa: The cast’s pictures were everywhere. They were mini-celebrities. Daphne and Adam were on the cover of Newsweek.

Pascal: I had the blond spiky hair and was extremely recognizable. I’m glad I had a taste of that visibility. I’m also glad I didn’t like it, because I’d probably miss it now that it doesn’t happen anymore!

Nikki M. James (actress, The Book of Mormon): I forget how many times I saw Rent, but it was in the twenties.

Leslie Odom Jr. (actor, Hamilton): I went to my local HMV — the cast recording had just come out — and I thought I’d listen to part of the album at one of the listening stations. I put it on, and I couldn’t move — I listened to the whole thing. There wasn’t a whole lot of art that looked like me and my friends.

James: There was this Rent line you could wait in to get cheap tickets each day.

McCollum: We decided, let’s make the cheap tickets the ones for the seats in the first two rows. At first it was first-come first-served, and it was a great visual — all these young people waiting on the street.

Seller: Within a year, the lines were so long that on Friday night you’d have three lines going: one for Friday night, people starting the line for the Saturday matinee, and the other people for Saturday night.

McCollum: It became a little Lord of the Flies — some people were getting robbed on the street. So we said, let’s do a lottery instead.

Pascal: Coming out of the stage door every night just got crazier and crazier. Sometimes we’d spend an hour signing autographs.

Martin: One of those crazy Rentheads who was at the door all the time was this tiny girl, always there with her best friend. I remember taking a picture with them and she looked up at me and said, “One day, I’m gonna be on Broadway, and you’re gonna come and see me at the stage door.” And something made me say, you know what, I believe you! Turns out, that girl was Nikki M. James, who won a Tony for The Book of Mormon.

Larson: My brother dreamed big dreams, and it all happened in this one show. Watching what’s happening with Hamilton, it feels so familiar. It’s that same raw, spontaneous, organic explosion of a show that Rent was.

VI. Rent goes on to win the Tony for Best Musical. It runs for 12 years.

Rapp: It started to become a little bit of a machine toward the end, and the cult around the show was in some ways not super-pleasant. The energy had shifted. It looked like I was going to be the last man standing of the eight original cast members, and that started to feel a little funky. The building was already full of ghosts.

Rubin-Vega: I was the first to leave because I got a record deal. And then a corporate merger put the kibosh on it. I was given a big fat check and no music.

Pascal: I got auditions for big films, and I blew every one. I was arrogant: “Why do I even have to audition? If you saw the show and you liked it, give me the part, what’s the fuckin’ problem?” There’s nothing worse than being famous and broke. I was still getting recognized for being Roger in Rent, but feeling like, do I have to get a real job? How do I get a real job after I’ve gotten a Tony nomination? What am I gonna do, work in a Gap?

Martin: Rent led to so many other things. I got a call that David Kelley was looking for a love interest for Calista Flockhart on Ally McBeal, and he wanted me to be the guy. I was used to auditioning like crazy, and I was just getting offered this role — how was that possible?

Telsey: Did Adam get the show Jesse got? No. Did it take time for Idina to go from Rent to Wicked? Yes. But I think the cast members were all finding their path. Twenty years later, they all have careers.

Menzel: Rent laid the groundwork for me. Its success gave contemporary composers permission to tell a story — to prove that building character [in a musical] is possible using pop and rock.

Rapp: The success of the show validated for me that when a group of people come together to tell a story they believe in, they can make a difference, which is the reason Jonathan wrote this thing.

Larson: Sometimes in the midst of talking to someone, I’ll say, “Oh, my brother wrote Rent.” And they’ll say, “Please tell him we loved it!” There’s a whole generation now who don’t know the story. Half the people now don’t even know Jonathan died.

*A version of this article appears in the May 2, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.