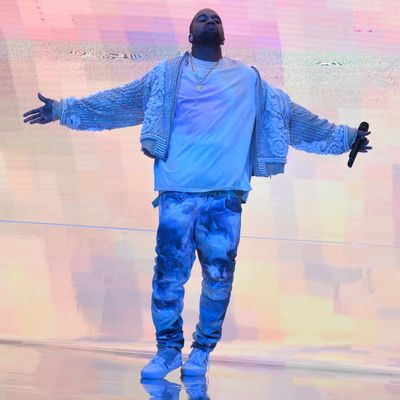

Kanye West often boasts that he is making the music of the future. That might be open for debate — but this week, he achieved an inarguable chart milestone that just might represent the future of hit albums, ones that might not look like albums at all.

On Sunday, Billboard made official what chart-watchers had been expecting since February: West has another chart-topper. The Life of Pablo, Ye’s seventh studio album — a project given a splashy release two months ago, then pulled and tinkered with by its creator before being deemed market-ready — is finally No. 1 in the U.S. It’s West’s sixth straight No. 1 debut on the Billboard 200 — his seventh straight, if you include Watch the Throne, his best-selling 2011 collaboration with Jay Z. Basically, Ye’s entire studio output since his 2005 sophomore album, Late Registration, has rung the bell on the Billboard 200, and Pablo maintains the streak.

Only this is the first of West’s No. 1s not to be America’s best-selling album. Actually, five albums sold more copies than Pablo last week. And if Billboard still ranked its chart based on which albums sold the most, Chris Stapleton’s nearly year-old album Traveller, fueled by a sweep of last week’s Academy of Country Music awards, would be spending its third cumulative week at No. 1, while West’s latest would place at No. 6.

The reason Pablo is instead sitting pretty at No. 1 has to do with the methodology change Billboard and data-provider Nielsen put into effect on the album chart 16 months ago. The Billboard 200 is now a “multi-metric” consumption chart that factors in streams and track sales, in addition to regular album sales, when determining the industry’s biggest albums. Straight-up album sales are still the single biggest factor in the chart, and most weeks, the No. 1 album and the best-selling album are one and the same, even after Billboard factors in all this data. But not this week — Pablo climbed the ladder thanks to its massive streaming sum: 99 million tracks were streamed from the album during the seven-day period.

Pablo therefore sets a milestone in Billboard chart lore: It’s the first No. 1 album to derive more than half its chart points from streaming services. To be exact, 70 percent of the album’s consumption last week was at streaming sites such as Apple Music and Tidal. Pablo was particularly huge on Spotify, the world’s biggest streaming service, which alone accounted for roughly 50 million streams, more than half the total.

For the vast majority of Americans, these streaming services are the only way to hear Pablo. The album is not out in any physical form, and currently digital copies are only for sale via Tidal and at West’s own website. In all, 28,000 copies of the album sold the traditional way last week. Actually, it’s hard to call even these album sales “traditional” — all are digital downloads (a physical release of Pablo is reportedly in the works for some future date, though likely not in CD form), and a large chunk of them were furnished to fans who attended West’s Yeezy Season 3 release party in February and paid extra for a future copy of the album, whenever it was completed. Those prepaid copies were finally sent to fans last week and, hence, count for this week’s chart.

But that’s not the only thing that’s nontraditional about albums that are streamed more than they are purchased. To calculate the album chart, Billboard and Nielsen do some basic math to make tracks and streams equal an album. They count 10 track downloads ($1.29 singles you buy on iTunes or Amazon) as equivalent to one album sale, and they count 1,500 track streams (songs you play on Spotify or Apple Music) as one album sale. These “equivalent album units” — converted track sales and track streams — now drive chart position. That’s regardless of which tracks are purchased or streamed; you don’t have to buy or play the whole album. You could stream the lead-off track on Pablo, “Ultralight Beam,” 1,500 times in a row, never hearing the rest of the album, and Billboard would tally that as an album sale.

Inevitably, some tracks on an album will be streamed more than others. Indeed, on Billboard’s new Hot 100 song chart, eight of Pablo’s 19 tracks were streamed enough times last week to make the list. “Ultralight Beam,” for example, was streamed enough times last week to land at No. 67 on the Hot 100 (impressive, since the song has minuscule radio airplay and no single-track download sales, the other metrics that go into the Hot 100). The two most played tracks on the album actually tallied enough streams to debut in the Top 40: “Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1” appears on the Hot 100 at No. 37, and the Taylor Swift-dissing “Famous” debuts at No. 34.

In other words, a streamed album is generally a cherry-picked album, not a full album. You can intuit this by studying the albums that have done well under the revised Billboard 200 methodology. In the 72 weeks since Billboard and Nielsen revised the album chart to count streams and tracks, there have been eight weeks where the No. 1 album on the official Billboard 200 chart differed from the top-selling album. Here’s a chart that breaks down those eight weeks, up to and including the new chart led by West’s Life of Pablo instead of Stapleton’s Traveller. (I have also included a breakdown of the data that got those lower-selling albums to the top of Billboard 200.)

That’s seven albums that nabbed the No. 1 spot over a better-selling album (seven out of eight chart weeks, because The Weeknd’s album pulled this off twice). Interestingly, they’re all R&B or hip-hop albums, including the soundtracks to TV’s Empire and the movie Furious 7. In general, R&B and hip-hop do especially well at streaming services, where hardcore fans sample current tracks in heavy numbers; for example, 2015’s top on-demand streaming song was Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen.” Rock albums, by comparison, are often at a disadvantage thanks to their less track-driven fanbases. Last spring the Furious 7 soundtrack stole No. 1 from pop-punk group All Time Low; and last fall, in two consecutive weeks, The Weeknd took No. 1 away from two different alt-metal bands, Five Finger Death Punch and Bring Me the Horizon.

But genre is only part of the story — the new track-driven methodology has worked out fine for pop acts like Taylor Swift and Justin Bieber. What really helps an artist on the new Billboard 200, more than anything, is the same thing that helps them on the Hot 100: hit singles. During those two weeks when The Weeknd snatched away the No. 1 spot on the album chart, he had two smash singles in the Hot 100’s Top Three; track downloads and streams practically doubled his album-chart math. Just three weeks ago, Rihanna set a new mark on the chart when Anti returned to No. 1 with an anemic 17,000 in album sales (in its first week on top back in February, Anti rolled a healthier 124,000 in pure album sales). What changed between early February, when the album came out, and early April was that Ri’s “Work” became a mega-smash, ultimately topping the Hot 100 for eight weeks. That week in late March–early April, her blockbuster single fueled 130,000 in purchased tracks and 36 million in streams, which, after Billboard’s mathematical magic, translated into an album-chart total of 54,000 units — 31 percent pure album sales, 24 percent track sales, and a whopping 45 percent streams.

Whopping, that is, until Kanye and his 70 percent streams figure. Of course, West’s Life of Pablo is something of a unicorn in that it has no real radio single, you can’t purchase individual tracks (yet) and its album-sales release is so limited. It’s hard to draw too many lessons or patterns from Pablo, given its schizoid release schedule, its temporary “living album” status, its weird exclusivity windows with Tidal and Yeezy release-party attendees, and its service-by-service streaming rollout. Even Billboard and Nielsen were at times confounded about how to track the album’s progress. “No doubt, this thing was an adventure from day one,” Dave Bakula, Nielsen’s senior vice president of industry insights, told me. “But the way that Kanye treated this as a living, breathing, changing project could prove to be an evolution in the way artists deliver music in the future.”

To me, the two most telling words in Bakula’s comment are evolution and project: That may be The Life of Pablo’s chart legacy. For years — long before Billboard changed its chart — the recording industry has treated albums less like indivisible, fixed works of art and more like marketing campaigns with catchy names like The Fame or Teenage Dream: “projects,” to use Bakula’s term. Labels have reissued hit albums with new radio singles grafted onto them, given them special-edition titles, and offered various retailers exclusive versions with special bonus content. Heck, long before Pablo — going all the way back to the Beatles’ differing U.S. and U.K. album editions under the same name, to say nothing of their vastly different mono and stereo mixes — the very definition of what was the “official” album was up for fan debate.

Billboard’s album chart has evolved to regard this mutability as a feature, not a bug. Without question, comparing a No. 1 album that sells as a total work to an album whose tally is inflated by a big hit single feels very apples-and-oranges. But The Life of Pablo has no hit single (save for one song it samples, Desiigner’s viral “Panda“), and it is being consumed every which way: as a total piece, as a Taylor Swift in-joke, or as a buffet of servings from Kanye West’s fevered mind. The music business is surely hoping there aren’t too many more Life of Pablos — after all, a major-label Project needs a predictable release schedule, one that’s not subject to one iconoclastic artist’s whims. But mark my words: There will be an all-streaming, no-sales No. 1 album on the Billboard 200 before we know it, and I wouldn’t want to bet that that album’s contents won’t change multiple times.