“I’m not black. I’m O.J.!”

Viewers of FX’s recent mini-series The People v. O.J. Simpson might remember that line from a jailhouse strategy session between Simpson and his attorneys about playing “the race card.” The significance of the line is self-evident: Simpson believes he has transcended racial identity. He is his own man, untroubled by the racial turmoil that affects other African-Americans and may have affected him in humbler times. He lives in Brentwood. His wife was white. He was in the Hertz commercials and the broadcast booth and all three Naked Gun movies. To think of himself as black would be to remind himself of a past that he’d run from, in as close to a literal sense as possible.

The superb “30 for 30” documentary O.J.: Made in America places the line much earlier, in 1968, when Simpson refused to join the ranks of other prominent black athletes who used their platform for political activism. In a way, the entire first episode could be considered a thorough unpacking of those two brief sentences. The FX miniseries unfolded over roughly ten hours, but as a dramatic narrative, it didn’t have the luxury to reflect on the entire history of race relations in Los Angeles to make sense of “I’m not black. I’m O.J.” Viewers get the gist, but they’re left to fill in the pieces themselves, based on whatever understanding of O.J. and L.A.’s past they might bring to the table.

After a prologue at the Nevada penitentiary where Simpson is currently serving 33 years for armed robbery — he’s up for parole next year, incidentally — O.J.: Made in America turns the clock all the way back on his life and the racial discord that he left behind. Director Ezra Edelman threads the personal and historical context of Simpson’s story beautifully throughout the first episode, with one informing the other and vice versa. It might come as a relief to Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden to know that the verdict was rendered long before Simpson’s trial began — long before Nicole Brown was murdered, even. The dynamics at play were established decades earlier, and Edelman goes back to the primordial ooze that made it all possible, to a city of broken promises that Simpson both escaped and exploited. Insert your football metaphor here.

Made in America starts with Simpson’s storied career at USC, where a game-winning, 64-yard touchdown rush (known simply as “The Run”) against rival UCLA made him a legend. Edelman gathers an impressive roster of talking heads to describe Simpson as a campus phenomenon — not just on the football field, where Coach John McKay called virtually every play for him and he won the 1968 Heisman Trophy, but as an unmistakable presence on a white campus. USC is depicted as a kind of bubble, free from the activism on campuses like Berkeley or San Jose State, and cordoned off from Watts, the neighborhood that sits on the “wrong” side of the Coliseum where Simpson’s Trojans played.

Edelman goes deeper still into Simpson’s childhood in San Francisco, where his family jammed into housing projects converted from old Navy barracks. His old buddies recall stealing cars, breaking into houses, and scalping tickets — and even at an early age, Simpson’s instincts for self-preservation were keen. A story about how he scammed his way out of trouble after his coach caught him and his friends shooting dice is so prophetic that it sounds like bad fiction: the young O.J. Simpson looking out for No. 1, allowing others to make hard sacrifices for him. The people around him are mere blockers, sacrificing their bodies so he can break to the open field.

On August 11th, 1965, two years before Simpson transferred to USC from community college, the Watts riots broke out. It was the tragic culmination of the era’s tension between the LAPD and the black community. Although the Rodney King verdict would color the Simpson trial closer to the date, yet again, Edelman makes the rightly compelling decision to flash back to the root of the problem. Made in America reflects on a time when L.A. was “the best place to be a negro” in the country, a land of milk and honey where blacks migrated from the Jim Crow South and the black population spiked 600 percent between 1940 and 1960. Meanwhile, the LAPD’s reputation for by-the-book professionalism, propped up by TV shows like Dragnet, obscured a culture defined by white supremacy, where cops didn’t protect and serve blacks, but strictly antagonized and apprehended them. One interview subject notes, ruefully, that the only difference between cops in the South and L.A. cops is that L.A. cops didn’t use dogs.

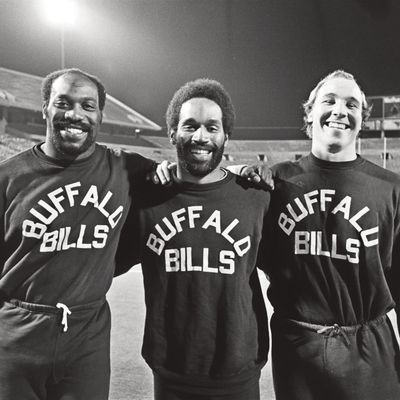

With all that context established, “Part One” covers Simpson’s NFL career in the frozen hinterlands of Buffalo, where he became the first running back to break 2,000 yards in a season. Off the field, he worked diligently to establish a non-threatening, white-friendly image. A section on his famous Hertz rental car ads is a revelation: Everyone remembers Simpson scampering through an airport, dodging and jumping over obstacles at top speed. But the image of a black man running through the airport was too threatening to stand on its own — it needed the validation of white people smiling in approval or cheering “Go, O.J., go!” He wanted to fit in, too. As we learn, he was anxious about getting his diction right.

Given that ESPN is chopping a seven-and-a-half hour movie into five digestible blocks, there’s bound to be some jagged inelegance with each ending. “Part One” takes us up to Simpson’s first meeting with an 18-year-old Nicole Brown at the Daisy in Hollywood, and his eagerness to fast-track her down the aisle despite the fact that he was already married to Marguerite Whitley, mother to their three children. Yet the endpoint makes sense, completing Simpson’s deliverance from the poor, black housing projects of San Francisco to the cloistered, white exclusivity of USC and Robert Kardashian’s tennis court. As the doors were kicked open by Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Muhammad Ali, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Simpson was more content to walk through them than join the fight. Race was a burden for him to overcome, right up until it became a courtroom strategy. Made in America isn’t done counting the ironies of that.

Correction: An earlier version of this recap made reference to Philip Glass’s Mishima score. The score was used in an unfinished version of Made in America that was seen by critics, but it was not included in the final cut.