If you’re a high-minded media consumer, you’re likely familiar with cartoonist Tom Gauld’s work — even if you’ve never opened a comic book in your life. His simple, evocative drawings show up regularly in some of the English language’s most revered publications, most notably The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, and The Guardian. He’s the guy who draws those little stick figures, oval-headed and expressionless, loping on long legs with slightly poor posture and often surrounded by simple mise-en-scène rendered in tactile crosshatch. Though his name is little known, his work is, in certain printed realms, ubiquitous.

Lucky for comics fans, that work is not limited to the world of editorial cartoons. He also creates charming mid-length narrative work. His latest book, Mooncop, comes out on September 20, and it’s a true delight, one you can devour in a sitting and feel sated for the rest of the day. Moreover, the book is one of the sweeter meditations on loneliness and isolation you’ll find on a shelf in any medium.

Despite a title that evokes some sort of late-’80s Jean-Claude Van Damme movie, the premise of Mooncop is quite serene: The last police officer on the moon (who remains nameless in the story) goes about his daily business while the handful of remaining lunar residents all peacefully return to Earth. The plot has no conflict or urgency. In fact, it’s a bit of a stretch to say there’s a plot at all.

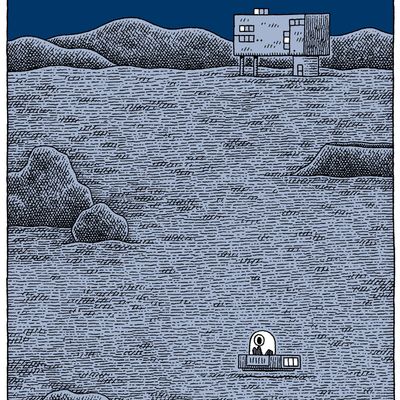

The book’s 94 pages are more a series of vignettes about a mostly solitary existence in a landscape that’s barren but not particularly harsh or threatening. To wit: The cop gets an alarm saying something is going on in Sector 6.3. He casually drives his space-car (it looks like a cigar box with three headlights and the plastic bubble from a game of Sorry! on top) toward the action. He finds someone skipping around on a small pile of stones that looks vaguely man-made.

“Hello, Lauren,” the cop says.

“Hey,” Lauren replies.

“You know you’re not meant to be out here.”

“I got lost.”

Then a panel of the cop’s silent face contained in his space helmet — perhaps he’s contemplating these words, perhaps he just doesn’t feel any urgent need to respond.

“It’s not like I’m doing any harm,” Lauren counters.

“I know,” he replies.

“Don’t you have any real crime to deal with?”

“Not really.”

He offers her a mild warning and a ride home.

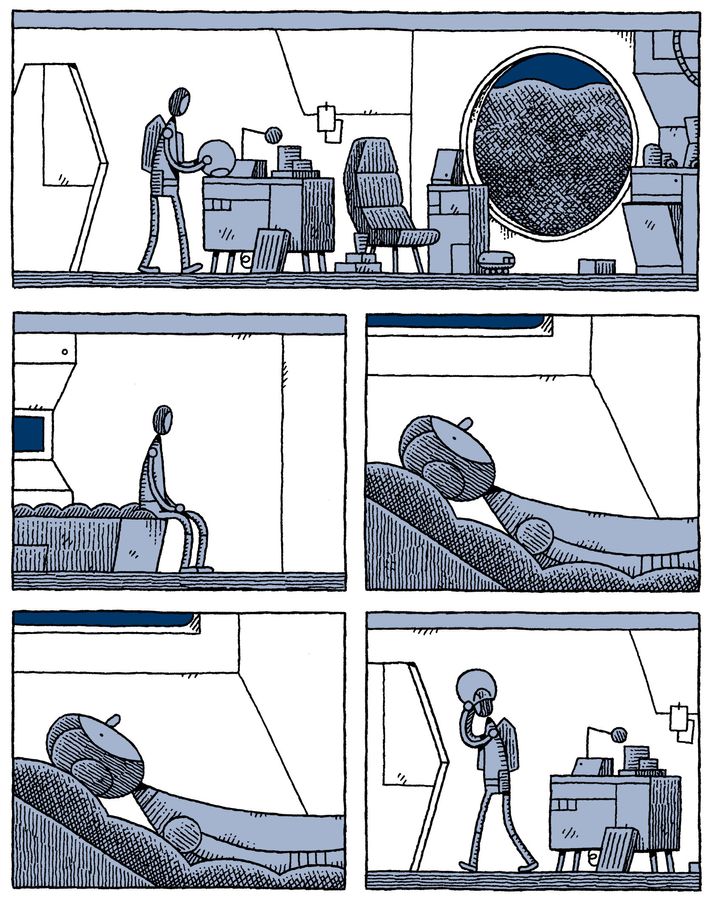

But the moon is not entirely mundane. It also possesses an abundance of deadpan humor. One great example: After the cop’s request to get restationed planet-side was denied, his Earth-based superiors thought he might be depressed — so they send him an R2-D2-esque robot to provide therapy. But in four sublime little panels, the droid follows the cop to the curb of the spaceport, then falls flat on its face before uttering, “I’m not equipped for rough terrain,” and the man whom the droid is supposed to be aiding affectlessly picks the machine up and carries it to his car. Or there’s the laugh we get from a wordless, full-page panel depicting a wayward dog trotting along in a little sphere on the moon’s surface. Gauld’s uncluttered renderings make a reader chuckle and smile at tiny moments like this, and as is true with all good cartooning, it’s hard to describe why unless you see them.

The population of the moon reduces itself to two by book’s end, and the cop’s sole companion is an employee of a doughnut shop. “I never thought much about the moon before I got this job,” she says in the wordiest page of the book — which only contains eight sentences. “But I love it here. I can spend hours just looking out at the stars and the rocks. It makes me feel very peaceful.” The cop stares blankly (then again, so does everyone in Gauld’s drawings) and responds, “It is very beautiful. I forget that sometimes.”

Mooncop is here to make sure we don’t forget. His comic is like printed Xanax. In a way, the lunar world the cop ostensibly patrols (at one point, he does his regular crime report and gets a 100 percent success rate from his computer because there were no crimes reported) is utopian. In this age of police brutality and violent retribution, how nice it would be to live in a world where the communities are tiny and calm, the officers of the law are chilled out, and the spaces are wide and open. Gauld has constructed a piece of relieving escapism. Sure, the Mooncop may not be getting off that rock anytime soon, and he seems unhappy with this fact. But loneliness can be appealing, in its own way. It’s unclear whether the cop understands this, but readers certainly will.