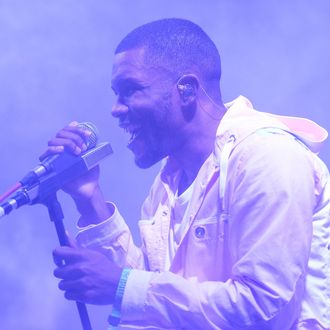

Another day, another Frank Ocean album: After many months of making needy fans hold their breath (and making editors and music writers hold their breath who, if not for their job, would have been perfectly fine with a release whenever, really), the young wizard of left-field pop unbound by genre distinctions released two collections in as many days. Both the “visual album” Endless and the album proper Blonde are extensions of their author’s mellow sensibility. Yet while Endless seems to lengthen the strain of lovelorn melancholy that’s been dominant in the artist’s work since his debut, Blonde marks a genuine departure: It’s far and away the happiest Frank Ocean collection ever committed to wax. Instead of being accentuated by their extreme contrast with deep, vivid orange, Frank’s native blues and blackness are framed by a full spectrum of hues: pink and mauve synthscapes, summer green, and gold guitars — and no small amount of whiteness. Frank’s never been big on antagonism, racial or otherwise. In his universe, there are no evil people, just people with differing motives and levels of indifference. So it’s not really a surprise to behold him absorbing sounds, styles, and people typically associated with whiteness and white people with the same loose, offhanded deftness with which he affirms his continuity with black culture and history. Here’s a brief guide to the whiter aspects of his varicolored album.

1. The title (and cover).

Like white skin itself, blond hair is the result of a melanin deficiency; like white skin, blond hair is most commonly found in Europe, particularly Northern Europe; like white skin, blond hair confers, or implies, a certain degree of social advantage. Even if most whites are dark-haired, the blond Caucasian remains the platonic ideal of white beauty. Frank’s late-breaking selection of Blonde over the original title of Boys Don’t Cry is the primary signal to listeners that he’s willing to remake whiteness in his own image. The very next indications, of course, are the white background to the album cover and the album’s cover photo, where the artist appears with his hair dyed blond on the sides (and green on top, because heaven forbid Mr. Ocean should send any unmixed messages).

2. The guitars.

Obviously there’s a long, rich heritage of guitars and guitarists in American black music: blues guitar, jazz guitar, rock-and-roll guitar, funk guitar. The prominence of guitars on Blonde is hardly anything white in and of itself. But the nature of those guitars — all those warm, soft, inviting, leisurely major chords (“Ivy,” “Self Control,” “Good Guy,” “Nights,” “White Ferrari,” “Seigfried,” “Godspeed”) — seems to owe far more to the Beach Boys and Beatles and any number of other distinctly white rock (not rock and roll) musicians of the ’60s and ’70s than it does to Howlin’ Wolf or Eddie Hazel.

3. “Seigfried.”

Whether he’s the tragic warrior-hero of pre-Christian Germanic myth, one half of a gay duo whose Las Vegas stage performances prominently featured white tigers and white lions, or a character who wields a sword as tall as himself in the fighting game series Soulcalibur (which Frank cited on Nostalgia, Ultra), there’s no doubt that Siegfried, as a name, is as white as it gets. You can chalk up the misspelling of the 15th track of Blonde to whatever you like, but be sure to use white chalk.

4. SebastiAn.

Not only did the Serbian-French electronic DJ and producer Sebastian Akchoté-Bozovic produce a few tracks for the Blonde sessions, this lucky guy, who is white, gets an entire track on the album to himself, recounting in heavily accented English how his unwillingness to accept a girlfriend’s Facebook friend request led to the demise of their relationship.

5. Berghain.

The Berlin club known as Berghain may not look like much from the outside, but for decades its cavernous interior has been a mecca for European electronic-music culture, drug use, and sexual experimentation, much of it public. On a Tumblr post last night that doubled as an epilogue for Blonde, Frank mentions how he visited Berghain to see things for himself.

6. Raf Simons.

On the same Tumblr post, Frank mentions how the Belgian superdesigner Raf Simons informed him that his obsession with expensive cars was clichéd. Frank goes on to speculate whether his car fixation represents some secret identification with straight masculinity on his part, but who knows. The only thing that’s certain is that he and Raf are on speaking terms.

7. “White Ferrari.”

Not only is the titular automobile of the 14th track of Blonde white, it’s manufactured by white people. There’s a really interesting argument to be made that Italian culture is the European culture most similar to black American culture, but for now it’s enough to say that, even if you managed to overlook the James Blake feature on it, “White Ferrari” is white, through and through.

8. “Pink + White.”

With its swinging rhythm and rich melodic bassline, “Pink + White” isn’t all that “white,” culturally speaking. But by choosing such a title for a song (as opposed to, say, the “black and yellow” also mentioned in the song), the artist is sending a signal. The word “white” featured twice on the track list is as close as you’ll get to a clear indicator from Frank that whiteness is a prominent theme on the album — we probably wouldn’t have noticed otherwise.

9. Yung Lean

A self-proclaimed “sad boy” rapper whose fans are almost all white American hipsters, the Swede known as Yung Lean (birth name Jonatan Håstad) seems to have contributed backing vocals to Blonde highlight “Self Control”; here’s hoping he’s less sad for having done so.

10. Hippie vibes.

Pacifism, free love, vivid colors, a warm, sunlit pastoral ambience, recreational use of hallucinogens — it’s a lot easier to find convergences between Blonde and the hippie spirit than it is to find differences. Frank’s album is yet another recent instance of psychedelic culture making inroads with black artists: Think of Chance the Rapper’s Acid Rap or A$AP Rocky’s “LSD” or Kendrick Lamar’s supergroup, Black Hippy. Hippie-affiliated cultural icons used to be predominantly white, but as boomers fade and the millennials rise, that looks to be changing. It sometimes seems as if Frank Ocean is picking up where Jerry Garcia or Joan Baez left off.

As shown by guest turns from Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, and André 3000, several black self-identifications in his lyrics, and a plethora of shout-outs to other black icons, the Frank Ocean of Blonde is as firmly embedded in black American culture as ever: His entry into sounds, motifs, and social circles long considered “white” is a sign of that culture’s autonomy and dominance rather than any dependence and subjection. But it’s also true that white listeners to Blonde can take heart from its ambience: Frank’s approval is an unequivocal reminder that excellence can emerge from associating with white people and white cultures. Not all of them, and maybe not even that many — but some, nonetheless.