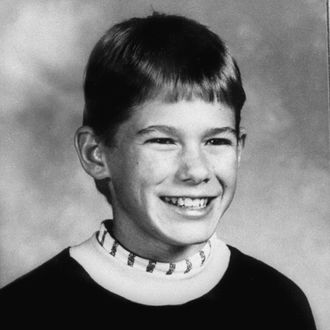

On the night of October 22, 1989, in the rural town of St. Joseph, Minnesota, two young brothers and their friend were biking home when they were stopped by a masked man holding a gun. He ordered them to lie down in a ditch, asked them their ages, then told the younger of the brothers and the friend to run away into the woods and not look back, or else he would shoot them. The other boy, 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling, was never seen again. His kidnapping haunted Minnesotans and led to the creation of a national sex-offender database, thanks in part to the activism of his parents, Jerry and Patty Wetterling. They never gave up hope that Jacob would be found.

Jacob’s disappearance is the subject of In the Dark, an eight-episode podcast from American Public Media that debuted earlier this month. Led by Peabody Award–winning journalist Madeleine Baran, the series was supposed to premiere on September 13, but then, on September 1, police broke the decades-old case: Daniel Heinrich, an early suspect in the disappearance who faced child pornography charges, confessed to murdering Jacob and led officers to the boy’s remains, buried on a farm. Five days later, the 53-year-old accepted a plea bargain to serve an expected 20-year sentence for the pornography, in return for admitting to abducting, molesting, and murdering Wetterling that night, as well as kidnapping and sexually assaulting another boy. “He’s not getting away with anything,” U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger told the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “We got the truth. The Wetterling family can bring [Jacob] home.”

After working on the podcast for nine months, Baran — who was at the courthouse when Heinrich gave his detailed, harrowing confession — decided to re-record the first two episodes of In the Dark and release them as soon as possible. She recently spoke with Vulture about the case, how her series differs from true-crime hits like Serial and Making a Murderer, what it’s like working with the Wetterling family, and the emotional impact of seeing the case closed.

How’s your week going? It must be pretty hectic.

It has been really busy. The one last piece of the puzzle is who did it and what did they do to evade arrest that night. To know that is so helpful as a reporter to try to tell this story. But it’s also a lot of information at once. We’ve been able to put that information right into some episodes we had plotted out, and it really backs up a lot of our findings even more. It didn’t change things as much as people might think. But I don’t know that this has happened before, where you have an investigative podcast and then there’s big breaking news.

When did you start the podcast?

About nine months ago. I’m not originally from Minnesota and when I moved here, if you said the name Jacob, everyone knew who you’re talking about. This case had led to a federal sex-offender law, it had fueled “stranger danger,” but I wasn’t here to live that experience. I’d always thought of it as “it must be this epic mystery, it must be unsolvable.” And then when I started looking at the details, I was surprised to see that it happened on a dead-end road. That it happened in a small town with few roads. That there were witnesses. Then the question was, “What went wrong?” The reason we would spend this much time on it is because this wasn’t just any child-abduction case. This had serious national consequences. It was a widely covered story, but a lot of the reporting was about the quantity — the number of helicopters, the number of officers, the number of searches. There wasn’t a whole lot of reporting about the quality of the investigation.

We’re trying to explore the consequences beyond not solving the case. What are the consequences to a community — in this case a small rural community — of not knowing who did this horrific crime? “Is it my neighbor? Is it the guy I worked with?” And what does that do to a place? What does it do when people accuse each other of this crime, based on no evidence, based on suspicion or “I don’t like this person,” what kind of dynamic does that create?

Your podcast is quite different from Serial and Making a Murderer. How did you think about approaching In the Dark in terms of what they’ve already done?

Both of those showed there’s an audience for this kind of longform serialized reporting. People will stick with it if they feel like the reporting and storytelling is solid. With Making a Murderer, people took away that there’s a problem with interrogation of juveniles, so that got a conversation started. Serial got a conversation started about the tunnel vision of investigators, among many other things. What’s different about our podcast is that we’re not looking at what happens if law enforcement convicts the wrong person. We’re looking at what happens if law enforcement doesn’t convict anybody. I hope one of the things our podcast generates is that conversation of “I wonder what the big unsolved cases are in my area,” or in the nation. “Are we giving law enforcement a pass here?”

Without having access to the case file, where did you start?

We reviewed all the old news coverage, [went to] the local historical society in Stearns County and read all the archives, a lot of other archival-type research. Then we went back and talked to as many of the original investigators that we could find, and we talked to current law enforcement. We went back to the very beginning. We talked to the babysitter who was at home. We talked to the Wetterlings. We talked to the people who lived on the block. One of the things we’ve revealed so far is that law enforcement didn’t talk to a number of people, even in the immediate area. It turns out that at least one kid saw, basically on the same dead-end road, some guy in a blue car six weeks before, who had tried to chase him. Now we know [Heinrich] had a blue car.

What was your initial meeting with the Wetterlings like? Did you have to sell them on the idea?

I had a conversation with Patty Wetterling very early on, saying, “This is something I’m going look into. Is there any reason there would be a problem?” She said, “No, go for it.” Then we started meeting with both Patty and Jerry Wetterling for some pretty long interviews. What they could tell us wasn’t necessarily what went wrong in the investigation. The focus was finding their son. But what they could help us understand was what this was like in a really intimate way. They were so generous with their time, going through that in the kind of detail and thoughtfulness that they did. It’s still so hard to understand what that would be like, but we wanted to show how this affects a couple, how this affects a family beyond the 20-second sound bite that often gets used.

Was the first episode already finished before Heinrich’s confession?

Yes. We talked about it and thought that the stuff that was coming early in the episodes was of great public interest. Our plan originally was to run episode one on the 13th, but we thought, “No, this is relevant now,” especially because we had the context on Heinrich and what happened that night. We knew he was headed to trial in early October, so we knew that this was not only a possibility, but that if it was going to happen, it was going to happen very soon. There were reasons to think he did it, but we weren’t prepared. Still, to be in that courthouse when this was happening was remarkable.

Emotionally, what it was like for you? Reporters have described it as devastating for everyone, family and onlookers alike.

I’m hesitant to say. It’s primarily the family. It’s their son. I don’t want to over-associate with someone else’s grief. But as a reporter, it was certainly the most difficult thing I’ve ever heard or read in court. I think it was something about the way that it unfolded as testimony. I assumed we were going to hear some graphic testimony about the sexual assault, but just to hear “and then this … and then this … and then I went home and I got a shovel and then I walked back and then I started digging the grave. And then I thought this was an awfully small shovel.” I was thinking about two things during that: “What is it like for the family to hear this?” and then, “What does this mean for how law enforcement acted?” It’s devastating on both of those counts.

The family is getting closure, but they’re also learning about Jacob’s final moments. It’s unimaginable.

It’s so awful. It was very visual and … it’s not going to be good, right? I cannot imagine if that was someone I knew, someone in my family.

And there were so many times Heinrich could’ve been caught.

Going chronologically, that’s interesting — you’re just walking on the road in the middle of the night with a shovel, and then you get there, and then you’re trying to dig a hole and it’s not working. And then you go to a nearby construction company, steal a Bobcat, turn on the lights, and drive it back? It’s like the most obvious way to bury a body. In general, it’s not what you’re expecting in a case that has not been solved. Then he went back to the site a year later. How are the remains just laying out there? It’s 1.2 miles from where Danny Heinrich was living in the center of Paynesville, so it’s not like some really far-out location. One of my questions is how did law enforcement, how did no one notice this? Because they made a replica of Jacob’s red jacket so people would know exactly what it looked like, so people knew “red jacket, Jacob Wetterling.” For the people of Paynesville to know that Jacob’s body was that close all along has been difficult for some, of course.

Knowing what you know now, are you rewriting the end of the series?

I can’t get into how it ends. [Laughs.]