Larry Wilmore’s closing remarks as the emcee of last night’s National Book Awards, held at Cipriani Wall Street in New York, could have sounded in isolation like a simple affirming joke: “This concludes, ‘BET presents the National Book Awards, with special guest Robert Caro.’”

The line was a nod to the fact that three of the four category prizes went to black writers — Colson Whitehead for fiction, Ibram X. Kendi for a history of racism, and Congressman John Lewis for co-writing a trilogy of YA civil-rights comics, The March. It was also the 66-year-old institution’s first year under the direction of a black woman, the young and ebullient Lisa Lucas. “Thank you so much for coming,” said Wilmore. “Keep reading, keep writing, and in the words of Kendrick Lamar, we gonna be all right.”

Everything did not seem to be all right outside the gilded former bank, or even inside the soaring space, which wasn’t big enough for the elephant in the room. Reminded early in the cocktail hour of Donald Trump’s victory, Whitehead chuckled and said, “The Masque of the Red Death.” That would be Edgar Allan Poe’s story about a party thrown in a futile attempt to ward off a plague. “Special guest” Robert Caro, author of the multivolume biography-in-progress of Lyndon B. Johnson, prayed there wouldn’t be much to fear. “I’m gonna say I have hope,” he told me. “Johnson said, ‘You ought to root for me to succeed, because if I fail you fail,’ and I keep thinking that’s the horrible truth. He is the president of the United States. As sick as we all feel inside — and I feel sick — you have to hope that something in the very nature of the Oval Office will bring out a different side of him than we’ve seen so far.”

Most others were less hopeful, but also less grave. They called to mind last week’s Saturday Night Live skit, in which Dave Chapelle and Chris Rock laughed bitterly as their white friends recoiled in shock from the election results. “Reversion to the mean — is that the expression?” said Whitehead. “We had a brief moment when things looked a little better and it’s only natural that evil resurfaces. That’s the push-pull of American history.”

Holding court near the bar, Walter Mosley was practically joyous. He wouldn’t give Trump the satisfaction of having gained power (much less the popular vote). “People in power are the people who are gonna respond to what happened in the election — that’s the power,” he said. “I’m not sure if that’s the people in this room, but I’m sure we’re in that mode. If you have somebody who represents you,” — e.g., Obama — “you’re less likely to stand up for what’s right. But now, you have no choice. So, hey, that’s great. America’s gonna have some fun.”

John Lewis, the 76-year-old congressman who was savagely beaten in Selma in 1965, bounded up onstage to accept the evening’s first award, for Young People’s Literature. “This is unreal, this is unbelievable,” he said, face streaming with tears. “I grew up in rural Alabama, very very poor, very few books in my home … We were told libraries were for whites only. And to come here and receive this award, it’s too much.” (Wilmore said it was fitting that Lewis was the subject of a comic, because he had a superpower: “Racism only made him stronger.”)

Offstage, the congressman flashed equal parts hope and defiance. “Be hopeful, be optimistic,” he advised. Was he optimistic? “I have to be. I almost died on that bridge [in Selma], but I never gave up.” He implores both his young readers and his House colleagues to do the same. “When I was growing up and I would ask my mother and my father about segregation and racial discrimination, about the signs that I saw, they would say, ‘That’s the way it is, don’t get in the way, don’t get in trouble.’ But Dr. King and Rosa Parks inspired me to get in trouble. I tell my colleagues, ‘We got to get in trouble. Good trouble. Necessary trouble.’”

On stage, trouble was on everyone’s mind. “A challenge to our incoming president,” said Nate Powell, one of Lewis’s co-writers. “I challenge you to take this trilogy into your tiny hands and let your tiny heart be transformed by it. None of us are alone in this, not even you.” Cornelius Eady, the co-founder of Cave Canum, a collective of black poets that received the Literarian award, invoked another gilded space in Manhattan: “Right now, as we speak, uptown there are people in a building that are trying to write a narrative about who we are and who we’re supposed to be and what to do about us. And when you allow that narrative to be taken from you, bad things happen. I think it’s our duty to make sure that we get to write our story … in our own language, in our own way.”

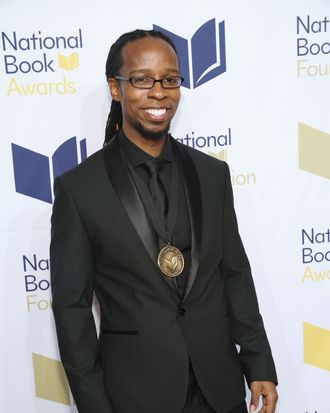

Introducing the nonfiction winner was head judge Masha Gessen, a Russian-American journalist whose most recent article is “Autocracy: Rules for Survival,” a six-point plan for enduring Putinesque decline. At first, she said, the nonfiction finalists seemed to make up “a very heavy list.” But “somehow over the last week it’s a list that’s begun to feel ever more timely and ever more urgent.” The winner was depressingly on the nose: Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas.

Kendi’s speech began as a litany of thank-yous, and it seemed he might not even address the elephant. But his final thanks went to his 6-month-old daughter; her name, Imani, means “faith” in Swahili. “It has a new meaning for us,” he said, “as the first black president is set to leave the White House and as a man who is emphatically endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan is about to enter … I spent years looking at the absolute worst in America, its horrific history of racism. But in the end I never lost faith that the terror of racism would one day end.”

“Let me tell you something,” said Wilmore. “The National Book Foundation is woke.” And then, as expected, Whitehead won the fiction award for The Underground Railroad, a heightened allegory in which the famous slave route is an actual railroad. It runs through Southern states that represent alternative realities in the landscape of American possibility. (You could think of our own conflicting realities — Obama’s “post-racial” world followed by its impossible opposite — in similar ways.) Whitehead confessed onstage that he had few ready answers for our current circumstances. “I’m sort of stunned,” he said. “But I hit upon something that was making me feel better. ‘Be kind to everybody, make art, and fight the power.’ That seemed like a good formula for me anyway. So: BMF. And if you have trouble remembering that, a good mnemonic device to tell yourself is, ‘They can’t break me because I’m a bad motherfucker.’ Thank you.”