If you, in 2012, watched Adam Driver on Girls — an unhinged, distasteful walking id, as magnetic as he was bizarre — and said to yourself, “This guy is going to be the cast’s biggest star,” you should probably start betting on horses. In recent memory, few actors have been marked by such a contradiction between the way they first broke out and the career they managed to forge as Driver. Jake Gyllenhaal comes to mind, as does Ryan Gosling; not coincidentally, along with Driver, those are three of the better actors under 40 working in Hollywood today.

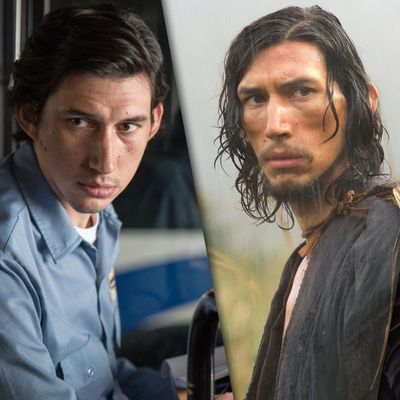

But even by those standards, Driver is remarkable. A guy who made his first impression as a hypersexed, feral carpenter on a show about Brooklyn millennials watched by slightly over half a million people is now playing, simultaneously, major roles for three incredibly different institutions of American film: Star Wars, where he’s the villain Kylo Ren; Martin Scorsese, for whom Driver plays a Jesuit priest in the maestro’s new epic of faith, Silence; and Jim Jarmusch, for whom he’s the titular bus driver in the indie icon’s new Paterson. Especially considering that the only thing more obvious than Driver’s gifts might be his presumed limitations — that topographic map of a face, that woodwind voice — the actor’s ascent raises the question of how exactly he became Hollywood’s go-to young actor of excellence.

The place to start in understanding Driver’s career is 1967, a decade and a half before he was born and the year that Mike Nichols’s The Graduate and Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde received Oscar nominations for Best Picture. As recounted in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, both films helped shatter the preexisting strategy of casting, which as casting director Nessa Hyams put it, involved selecting from the platter of “nondescript, blond hair, blue-eyed” Ken dolls that studios had under contract. Penn and Nichols filled their films with New York theater actors who “resembled real people,” and Nichols delivered the pièce de résistance by casting Dustin Hoffman, a Jewish actor who looked like a Jewish actor, in The Graduate instead of Robert Redford.

“I told Redford that he could not, at that point in his life, play a loser like Benjamin, ‘cause nobody would ever buy it,” Nichols told Biskind, and the two movies — in addition to representing the tip of the spear of New Hollywood — opened the floodgates for ethnic- and unconventional-looking actors like Hoffman, Robert De Niro, Gene Hackman, and Al Pacino, who would come to dominate screens in the ’70s.

Of course, the ‘70s also gave us blockbusters like Jaws and Star Wars, the two films that did the most to bring about the modern tentpole era, which comes with its own casting demands. Blockbusters today need to play overseas and across all demographics, an incentive that, combined with the public love of muscle-bound superheroes, has resulted in our most famous actors all appearing mostly alike: white, tall, noble, physically flawless. In at least one case — that of Chris Evans, Chris Hemsworth, and Chris Pine — they even have the same name. But more than these three, who take a disproportionate brunt of the criticism for this phenomenon, the roles were to blame for the homogenization of actors. The majority of blockbusters follow the same beats and same arc. Their stars have to deliver the same emotional journey; it makes sense that they’re all the same.

In 2014, Chris Pratt, our most recently minted movie star, became the exception to one of these rules — he was actually allowed to have an onscreen personality, which was essentially an update of Harrison Ford’s wisecracking but good-natured vagabond. But Pratt was still conventionally good-looking, still made to become anatomy-class muscular, and still, even named Chris, which just proves how narrow the lane really is. Meanwhile, the dearth of minority actors in major roles became an especially concerning parallel problem; for actors of color, there wasn’t even a Chris to aspire to being.

But like Hoffman, De Niro, Pacino et al., Driver — and to a lesser extent, his onetime Girls co-star Christopher Abbott — came from a working-class background, plied a distinctly un-Hollywood trade before acting, in this case the Marines, and then trained in the theater before landing in television and film. As if by magic, he offered up authenticity, acting chops, and a contrast to the cookie-cutter casting situation that had come to plague Hollywood, which had prompted directors of ambition chose to either stick with older actors like Leonardo DiCaprio, Joaquin Phoenix, and Bradley Cooper, or cast British, Irish, and Australian actors like Michael Fassbender, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Christian Bale as Americans.

If it appears Driver was discovered all at once, that’s because he pretty much was. In the two-year span of 2012 and 2013, Driver worked with Steven Spielberg (Lincoln), the Coen brothers (Inside Llewyn Davis), and Noah Baumbach (Frances Ha), at the same time he was appearing in the freshman and sophomore seasons of Girls. In 2014, he starred in the Italian thriller Hungry Hearts, for which he won Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival, as well as Baumbach’s While We’re Young, and This Is Where I Leave You, a mediocre ensemble family drama that nevertheless allowed him to outshine a handful of other famous co-stars. Unlike many young actors, who get cast off the strength of one performance or success, Driver was being found simultaneously by a number of different directors. His appeal was innate.

By February of that year, Variety was reporting that he’d been cast as the villain in The Force Awakens, capping a dizzy liftoff. In the September 2014 GQ, filmmakers sang his praises. Shawn Levy, the director of This Is Where I Leave You, put it, “The way he moves, talks, eats, navigates the world … It’s really authentic. Adam is a fucking man.” Said Baumbach: “He’s a real person.”

Those comments point to one of the subtler differences between the actors of New Hollywood and today. In The Graduate, The French Connection, and Mean Streets, Nichols, William Friedkin, and Martin Scorsese were trying to evoke specific places, times, and populations with their casting of Hoffman, Hackman, and De Niro and Harvey Keitel: Beverly Hills Jews, New York City cops, young Italian-American strivers. That kind of ethnographic filmmaking is still around, advanced and explored by directors like Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay, Ana Lily Amirpour, Barry Jenkins, Shane Meadows, and Andrea Arnold. The authenticity Levy and Baumbach allude to is more general, a feature that often gets lost in the frenzy of casting, when a million different people need a million different boxes checked. Driver is an original piece of work, an actor who only resembles himself. And while plenty more people don’t resemble movie stars than do, there’s a reason why most aren’t high-profile actors. To convincingly project your own individuality in a medium in which you are instructed, by just about everyone, to do exactly the opposite — to model yourself after someone who is already famous and successful — is a task that requires exceptional clarity of self; and yet, you still need to let just enough of other people in, so that directors and audiences can see something in you.

Much of why Driver is able to do this is because he has one of the most useful skills an actor might possess: He can modulate the volume of his performance. He can be impactful as part of an ensemble, like he is in Girls, This Is Where I Leave You, and The Force Awakens, coming in loud and brash, making the most of his scenes; in these projects, when he’s offscreen, you wait for him to reappear. Alternatively, he can play quiet and restrained, neither exhausting nor losing the viewer. In Paterson, Driver barely does more than think and listen, and yet he’s a magnetic presence. He has the exceptional ability to let you see him thinking and listening.

Because of Driver’s control, he can go from the charismatic hipster-swindler of Baumbach’s While We’re Young to the quiet, unassuming, awestruck scientist in Jeff Nichols’s Midnight Special. And because he’s so singular, he can play a doomed Jesuit priest for Scorsese, a bus-driving poet for Jarmusch, and an evil Jedi for J.J. Abrams, all while making the films he’s in more convincing as independent worlds. He’s the rare male performer who could be as convincing a ballet dancer as a boxer, bruising and sensitive in equal measure. Among the current crop of top-tier actors, few possess that kind of versatility. (It certainly isn’t asked for.) But Driver has it whether he wants to or not. Nobody will ever mistake Adam Driver for someone else, and in today’s Hollywood, that in itself is unique.