Tom Hardy is out of character. The 39-year-old Englishman became famous by playing intense, often frightening men: the titular convict in Bronson, the psychotic Kray twins in Legend, the backbreaker Bane in The Dark Knight Rises, and Fitzgerald in The Revenant, who left a grizzly-maimed Leonardo DiCaprio to die in snowy woods. His character in the BBC-FX co-production Taboo is on-brand: James Delaney, a snarling 19th-century adventurer who returns to London to claim his late father’s inheritance and brings the legacy of England’s imperial sins back with him. But on this snowy December afternoon, Hardy stands in the corner of his room at the Ritz-Carlton on Central Park South, clad in skinny jeans with high-water cuffs, a gray shawl-collar cardigan, white sneakers, and a Texas A&M cap sent to him by an American fan, bobbing excitedly as he scrolls through drawings of Marmalade, a plump orange cat that he created for 9-year-old Louis, the oldest of his two children. Hardy’s gallery of iPad images showcases the feline clothed and posed in the style of mythological and royal figures, adventurers and soldiers. “He’s my son’s bedtime story,” Hardy says. “Marmalade lives in Zanzibar, in a palace called Shazaam, with Sultan Lord Fezzik Fozool, a very rich sultan. He is basically a wizened old fat cat who likes to sleep in his hammock in the sun and do nothing. A bit like Garfield, really, though he does get into scrapes.”

Marmalade is Hardy’s way of carrying on the storytelling tradition of his own father, novelist and comedy writer Chips Hardy. Father and son devised the concept of Taboo together, then handed it off to screenwriter and executive producer Steven Knight (director of the film Locke and creator of the TV series Peaky Blinders, both of which featured Hardy). The result is a big-budget, TV-MA version of the sorts of collaborative flights of fancy the Hardys enjoyed when Tom was a boy. The elder Hardy used to lull young Tom to sleep with the adventures of Colonel Frobisher, a military officer from the era of “big mustaches and lots of plumes … He’d put him in the desert with T. E. Lawrence. I was assured that Colonel Frobisher was a real person, but it turns out he wasn’t!”

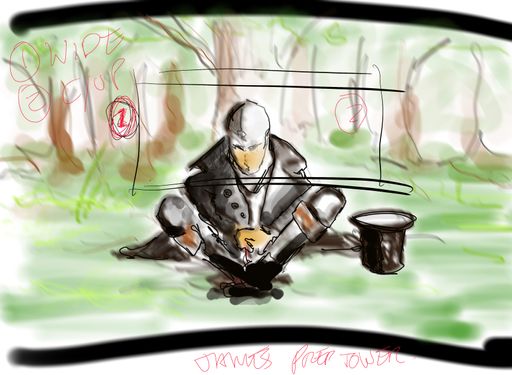

The younger Hardy’s drawing talent comes by way of his mom, Elizabeth Anne Hardy, an artist. The actor writes and doodles compulsively; a notepad lying on a windowsill in his hotel room is festooned with line drawings reminiscent of Quentin Blake, Roald Dahl’s regular illustrator, sandwiched by blocks of barely legible script. The same iPad that chronicles the glories of Marmalade contains Hardy’s drawings and paintings of his movie characters, including Fitzgerald, Bane, and explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, whom Hardy will play in an upcoming biopic. There are individual images of Taboo’s Delaney in poses that Hardy assumes onscreen in full costume, created days or weeks before the shoot. It’s this complex creative lineage that makes Taboo so personal: The FX series is at once a gallery of line drawings, a ghastly bedtime story, a muckraking melodrama, and a family project.

Matt Zoller Seitz: Why did you decide to do TV? It’s not like you lack feature-film opportunities.

Tom Hardy: I wanted to do my own stuff, and I also wanted to work in a medium where I could have more time to tell a story. And I wanted to work with my dad and Steve Knight. This is my father’s story and Steve Knight’s story, and I’d loved working with Steve on Locke and Peaky Blinders. Also I wanted to work at home, on the BBC — come home, you know? I know I sound really silly, but I started out on the BBC and wanted to put back in to where I’m from. I came up with the character [of James Delaney] and then Chips came up with the story.

MZS: So Delaney started out as a character without a story?

TH: Well, I worked on Oliver Twist [on the BBC in 2007] playing Bill Sikes, and I really enjoyed it.

MZS: That’s funny — with Delaney’s top hat and his walk and those 1820s-London sets, my first thought was, This is a Charles Dickens novel with a Clint Eastwood character at the center.

Drawings by Tom Hardy; Photograph courtesy of FX

TH: Yes! And there’s a bit of Sam Peckinpah in the vibe as well. The thing definitely started to turn into a Western by the latter part of filming. On the page, there was also a bit of Marlow from Heart of Darkness, and a bit of Hannibal Lecter, Oedipus, Heathcliff, Sherlock Holmes, Robert De Niro in The Mission, and Klaus Kinski in Aguirre: The Wrath of God. A lot of different classical characters amalgamated into one. My father was like, “Tom, that’s an awful lot of people to put into it.”

MZS: A lighthearted bunch, too!

TH: What interested me about Bill Sikes was, fundamentally, he’s a bit of a hero, but he’s played as a bad guy. All these characters are pretty mercurial and have a bit of naughty in them, too, but they’re doing a noble thing. If you go back into the history of classical texts and look at characters like Oedipus, Electra, Agamemnon, you think, Fuck — these people have pretty horrific things going on in their lives, but they’re the heroes! Can you make someone heinous likable?

MZS: Your Taboo character is described on the show as an “adventurer of very poor repute … defined by stories of madness, savagery, theft, and worse.” While in the service, he broke the necks of officers and set a boat on fire. And there’s some things in his past involving the slave trade that are so horrendous that the first three episodes of the show can barely bring themselves to allude to them.

TH: There’s a line of Delaney’s: “I do know the evil that you do because I was once part of it.” It’s the concept of taking somebody to the brink of numbness from participating in purely heinous acts. That is something he can never, ever, wash away. He cannot wash away his accountability and responsibility.

MZS: You’re talking about the dominant culture in England at that time?

TH: The dominant culture at every time, everywhere. He who hath the biggest hands eats the most.

MZS: It’s not as though you’ve never faced that challenge as an actor before. A lot of the characters you’ve played that have made an impression on viewers are —

TH: Bastards? [Laughs.]

MZS: Well, yes — objectively, bastards. But more than that. Often you play villains who think they’re the heroes of their stories. Bane, for instance — he’s really the main character of the Batman movie you were in, and his motivations have an emotional logic even if they’re politically incomprehensible.

TH: Bane loves the sound of his own voice. You laugh at him, but there’s also a feeling of truth to what he’s saying. That’s always true of demagogues. They’re clownlike, and yet they have an incredible amount of power. The appeal for me in playing villains or baddies, or however you want to put it, is that there’s often a lot more in the way of the subtleties and complexities and paradoxes of the human condition to play with than there is in a straight lead.

MZS: I often hear actors say they have more fun playing the sidekick, the villain, the foil, or the eccentric who has one or two juicy scenes, because the good-hearted action hero or the romantic lead is never as interesting.

TH: By default, by default. Things happen to them; they don’t make things happen. There’s a laziness in storytelling whereby you present the character as a blank canvas and then you throw a lot of stimulus at the character and you just follow this blank canvas through various rooms where we meet the actually interesting people. But if you have your protagonist fully faceted in ambiguity and hypocrisy and the paradox of true heinous wrongness, combined with innate nobility, well, that’s more interesting to watch. Great Expectations, Oliver Twist. It’s all there. The Shakespeare tragedies. Or Marlowe with Faustus.

MZS: The Old Testament —

TH: The Old Testament! There you go! Pestilence and famine! [Laughs.] I liked the stories from the New Testament, because Jesus was a cool guy who did some pretty cool things and miracles. But the Old Testament was swathed in chaos and Dionysian behavior. The Old Testament is Wagner and Mahler.

MZS: You’re the first actor I’ve met who finds his character by making sketches.

TH: One has to have a silhouette, you know? Say I’m playing Elton John. You know what he looks like. Playing Al Capone. You know what he looks like. But what about characters we’re making up from scratch, who you don’t know what they look like? You have to create a memorable silhouette for them, too.

When I was at school I was told, “Tom, when you play the prince or the king, I want to fucking see a king walk onstage before you even open your mouth. What does that look like?” Do you do it literally, with a costume, or through physicality? How do you immediately see the king? Crown? Robes? I have to find an identifier, a silhouette which immediately radiates something for me. Remember, you won’t necessarily know by their clothes that they’re the king. You can walk on in a disheveled homeless man’s outfit, but there’s something about them that radiates a nobility, something that makes you go, “This person’s a king.”

*This article appears in the January 9, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.