It pains me to say it, but I am a failed artist. “Pains me” because nothing in my life has given me the boundless psychic bliss of making art for tens of hours at a stretch for a decade in my 20s and 30s, doing it every day and always thinking about it, looking for a voice to fit my own time, imagining scenarios of success and failure, feeling my imagined world and the external one merging in things that I was actually making. Now I live on the other side of the critical screen, and all that language beyond words, all that doctor-shamanism of color, structure, and the mysteries of beauty — is gone.

I miss art terribly. I’ve never really talked about my work to anyone. In my writing, I’ve occasionally mentioned bygone times of once being an artist, usually laughingly. Whenever I think of that time, I feel stabs of regret. But once I quit, I quit; I never made art again and never even looked at the work I had made. Until last month, when my editors suggested that I write about my life as a young artist. I was terrified. Also, honestly, elated. No matter how long it’d been — no matter how long I’d come to think of myself fully as a critic, working through the same problems of expression from the other side — I admit I felt a deep-seated thrill hearing someone wanted to look at my work.

Of course, I often think that everyone who isn’t making art is a failed artist, even those who never tried. I did try. More than try. I was an artist. Even sometimes a great one, I thought.

I wasn’t totally deluded. I was a lazy smart-aleck who felt sorry for himself, resented anyone with money, and felt the world owed me a living. For a few years, I attended classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, although I didn’t always pay tuition and got no degree. But I did meet artists there and saw that staying up late with each other is how artists learn everything — developing new languages and communing with one another.

Watch Jerry Saltz review his artwork.

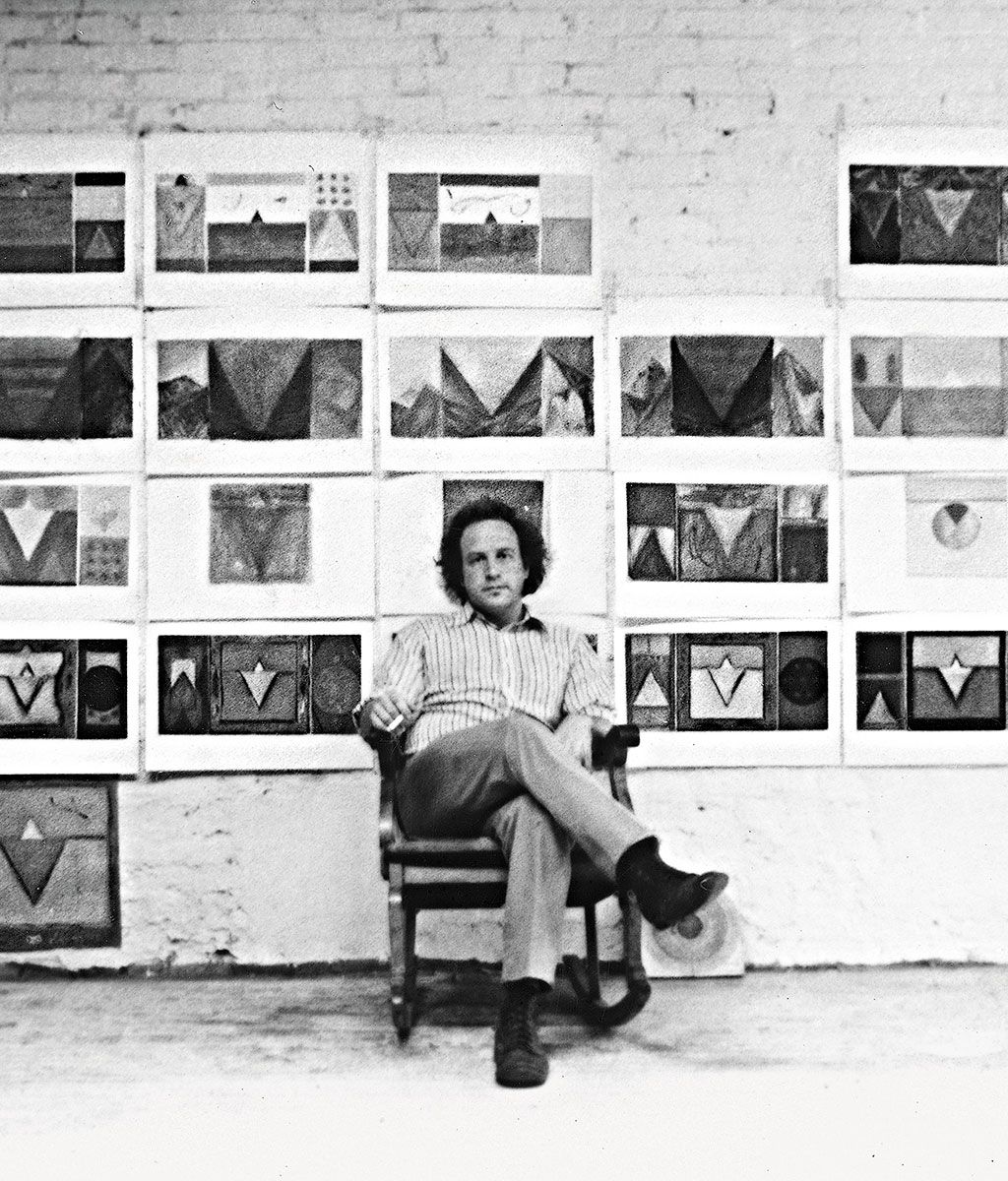

In 1973, I was 22, full of myself, and frustrated that I wasn’t already recognized for my work. I walked into my roommate Barry Holden’s room in our apartment, 300 feet from Wrigley Field, and said, “Let’s us and our friends start an artist-run gallery.” He said, “Okay.” It was great! People took notice; articles were written; I was interviewed by bigwig New York critic Peter Schjeldahl; I met hundreds of artists and felt part of a huge community that I fancied I was near the center of. For years, I lived across the street from the gallery, in a huge cold-water sixth-floor non-heated walk-up loft that had a $150 monthly rent. The place had previously been a storage facility for Jerry Lewis’s muscular-dystrophy foundation, and my furniture was mostly what had been abandoned there: a wooden bench for a couch, a huge drafting table in the center of the space, a hot plate, buckets on the floor to catch the leaks from the ceiling, a pail to fill for pouring down the toilet to make it work, and a mattress on the floor. I was an artist.

By 1978, I’d had two solo shows at our gallery, N.A.M.E. (called that because we couldn’t think of a name). Both shows were part of a gigantic project that I began the day before Good Friday in 1975. I was illustrating the entirety of Dante’s Divine Comedy — starting with “Inferno.” Both exhibitions sold out; museums bought my work; I got a National Endowment for the Arts Grant — the huge sum of $3,000, which, with an artist-girlfriend’s help, enabled me to move to New York. I was reviewed favorably in Artforum and the Chicago papers. My work was in the proto–Barbara Gladstone gallery in New York as well as shown by the great Rhona Hoffman in Chicago. I was delirious. Mice crawled on me at night; I showered at other people’s houses and had no heat. I didn’t care. I had everything I needed.

But then I looked back, into the abyss of self-doubt. I erupted with fear, self-loathing, dark thoughts about how bad my work was, how pointless, unoriginal, ridiculous. “You don’t know how to draw,” I told myself. “You never went to school. Your work has nothing to do with anything. You’re not a real artist. Your art is irrelevant. You don’t know art history. You can’t paint. You aren’t a good schmoozer. You’re too poor. You don’t have enough time to make your work. No one cares about you. You’re a fake. You only draw and work small because you’re too afraid to paint and work big.”

Every artist does battle, every day, with doubts like these. I lost the battle. It doomed me. But also made me the critic I am today.

II.

I still wonder, Was I fated by my upbringing to failure? Art certainly wasn’t in my life in the Chicago suburb where I grew up, except cheesy reproductions of French-ish Impressionists in our rec room.

But when I began as an artist, my main spiritual-home museum wasn’t the Art Institute — even though I spent hours there, spellbound. It was Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. I loved that the work here wasn’t freighted with art history, and I felt freer fantasizing about it. More important, I loved that it was all for more than just looking at: It was meant to cast spells, heal, protect villages from invaders, prevent or assist pregnancy, guide one through the afterlife. I was into Northwest Coast, Plains, Southwest, and South and Central American art. My favorite abstract painting was Navajo sand painting, Oceanic art, and the newly revealed work of Swedish visionary Hilma af Klint. All this work felt driven by innate spiritualism and inner necessity, as opposed to the abstraction coming out of New York.

What did the contemporary-art world look like to me then? I loved Nancy Graves’s sculptures of stuffed camels, Eva Hesse’s gnarly materials in space, Lynda Benglis’s giant poured-paint blobs coming off the gallery wall, Jennifer Bartlett’s process dot paintings. And the work of my friends. At the time, I imagined that our nonrepresentational, process-or-performance-based, and conceptual art would save Chicago from a group of artists whom I now love, the figurative surrealists — Jim Nutt, Roger Brown, Christina Ramberg, Gladys Nilsson, and Jeff Koons’s teacher Ed Paschke — known as Chicago Imagists.

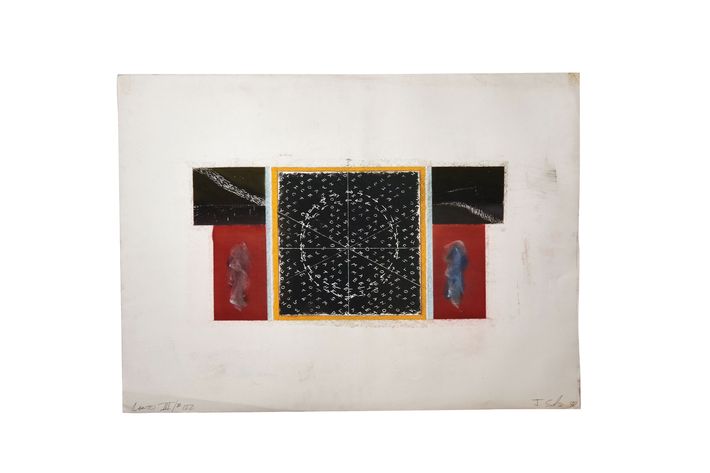

But art history was more important to me, particularly Byzantine, medieval, early Sienese painting, Native American art, Tibetan mandalas, Japanese prints, all of the Baroque, everything from the Northern and Southern Renaissance. I especially loved the cryptic illustrations, charts, and diagrams dealing with magic, mysticism, and visual mnemonic systems made by Renaissance artists most people have never heard of (like Robert Fludd, Athanasius Kircher, Giordano Bruno, Ramon Llull, Giulio Camillo). By the time I was 21, I was making hard-edged geometric drawings and paintings based on the I Ching — which looked a lot like Southwest Native American art and pre-Columbian Peruvian feather art — thinking they could tell the future.

Another regional strain coursed through me, too: Chicago’s powerful connection to self-taught and outsider artists. I saw and loved the great outsider Lee Godie selling her drawings on the steps of the Art Institute; I admired the work of the self-taught Joseph Yoakum, who was promoted by many of the Chicago Imagists. The work of two outsider masters was discovered and embraced by Chicago in the 1970s: Martín Ramírez in 1973 and Henry Darger in 1977. I was a guard at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art during its show of Adolf Wölfli. I even worked at Phyllis Kind’s New York gallery, the Chicago dealer who showed many of these Imagists and outsiders. I wanted to be an outsider worm in the bowels of the insider hyena.

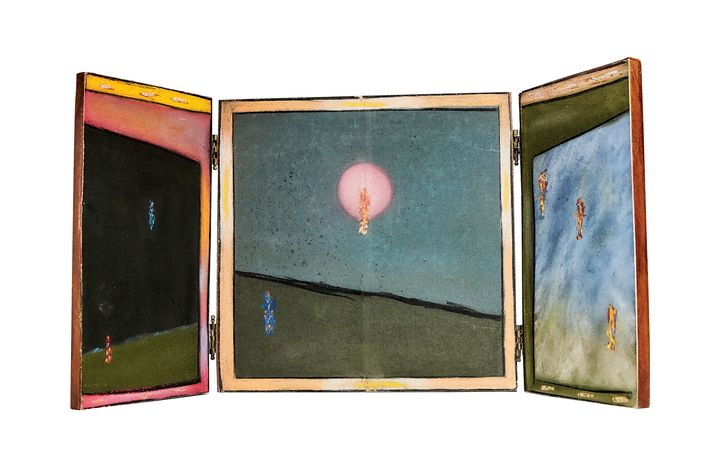

I began my “Inferno” project just before dawn on the Thursday before Easter 1975, because Maundy Thursday is when Dante’s story begins in the poem — lost in “the dark wood of error,” having strayed from the “true way.” I planned to finish on Easter, the same day Dante finished his own journey, in 1300. I would finish in 2000, by which time I would have made 100 opening-and-closing altarpieces for each of the 100 cantos of The Divine Comedy. The 10,000 finished altarpieces were supposed to represent an idea of the infinite and a way to set myself free. Why Dante? Especially as I barely read at all and didn’t believe in God? I think because The Divine Comedy, which is a gigantic organized allegorical system where every evil deed is punished in accord with the law of equal retribution and divine love, supplied me with the formulated structure I craved. The highly established internal architectonics, the almost primitive definitiveness, what Beckett called the “neatness of identification,” were psychological shelter and weapons of revenge for me. A way to right my own world, to grasp an order like that in the Bible: “all things by measure and number and weight.” Most of all, it was a vision of justice — the good being rewarded and the bad getting their punishments.

All of this seemed like a powerful counter to the chaos of my childhood. My mother committed suicide when I was 10, and I was never really told; I did not go to the funeral, and she was never spoken of again in my life. My father remarried shortly thereafter, to a Polish Catholic woman with two sons — one of whom was my age, so that I felt I had to go to war with a twin. There was drug use by my step-twin in the house, my committing petty crimes and being caught by the police. I — but not my stepbrothers — was beaten, sometimes with a leather strap fashioned in the shape of my father’s hand; it hung on the refrigerator door. This was in our otherwise stately suburban home, where the children and parents had absolutely no overlap — down to different dining rooms and entrances to our home, which came to feel almost like compartments. Or Hell.

Dante’s world was also compartmentalized, but enormous — the most systemized megacosm I’d ever seen. It was a galaxy of good and evil, catharsis, sin, injured spirits, saints, battle scenes in Heaven, a fallen world, those waiting for redemption, monsters, yearning, shame, Satan, and rising again. I did not believe, in the conventional sense of the word, but Dante’s metaphysical, moral architecture got me through my 20s at a time when I had no internal structure whatsoever. (Or perhaps I had one that was already collapsing under the weight of its own repressed pain, rage, loss, self-pity, and fear.) Dante is a paradigmatic figure of the canon — therefore a perfect picture of the dream of artistic canonization — but he’s also a weirdo Boschian fantasist and so satisfied my obsession with hermetic traditions, indexes, myth, archaic cultures, and mystics and visionaries like William Blake. This late-medieval universe freed me from making choices; the story and structure told me exactly what to do, what to draw, where to draw it, what came next, what shape things should be, everything, even sometimes governing colors, as with making Virgil blue and Dante red according to past art. Without knowing it but in desperate need, I’d contrived a machine that allowed me to make things that I couldn’t predict; I still think of this as one of an artist’s first jobs.

I made art obsessively. I’d wake up and go down to the local diner at the corner for coffee and breakfast, smoking, reading the sports section. After breakfast, I’d stand at my desk all day and work while smoking and listening to my music — 1970s rock and disco — on an old tube radio that had no covering, just the guts. Lunch was at the same place; dinner at one of two nearby local bars, where I was a pinball champion. I also won a local pool tournament. Other times I’d nurse beers and talk to artists, or go to Chicago’s great jazz and blues clubs, which were so underattended that I met all these living gods simply by showing up.

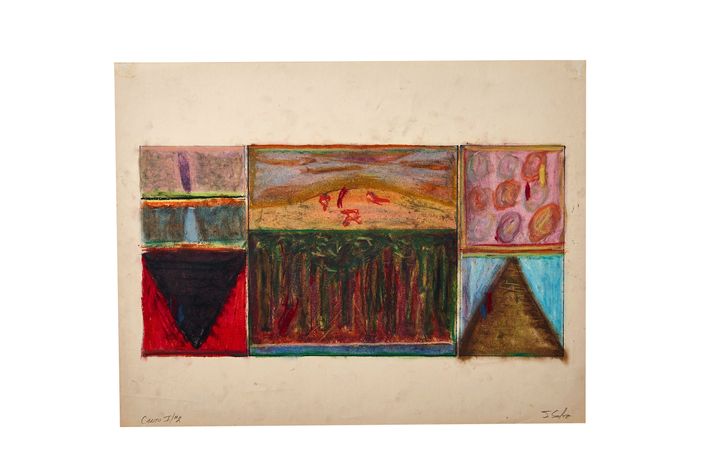

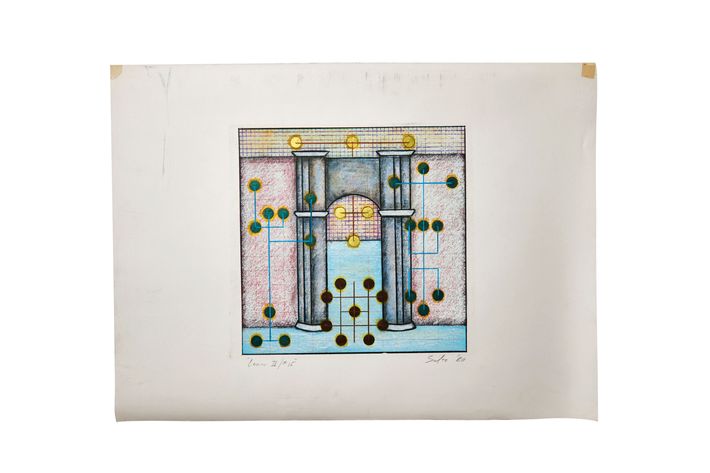

I worked on paper because I didn’t have a choice. I had no carpentry skills, had tried to make stretchers but failed miserably. Canvas was out. So were wood or Masonite panels: too heavy, expensive, large, and I didn’t know how to cut them. My medium was pastel, charcoal, and colored pencils, because I was too much of a smarty-pants to ever learn to paint. After all, painting was dead and only losers made it. So I would use my hands and rub, drawing over, making ruler lines, scratching on, blurring this supersaturated pastel. Every minute or two, I’d take a huge breath and blow all the colored dust off the drawing. (The space around my desk looked like a coal mine.) To this day I’m convinced that my being prone to upper-respiratory infections comes from years of breathing this at close quarters. I didn’t know what I was doing but knew how to do it and had the feeling that I was doing it to save my life. Okay. I was delusional.

My process was as structured as the rest of the project. I made paper and cardboard templates so every drawing could be the same size and similarly laid out. Since I knew I couldn’t really draw, I turned to drafting tools. I had none of the technical skills you were supposed to be taught in school (what an asshole I must have been), so the tools helped immensely: They were cheap, small, easy to use, and fun to misuse. They let me measure everything and be able to make the same thing over and over again. This meant that my symbolism, shapes, and system were all semi-geometric. Yet it never occurred to me that I was making geometric abstraction. The thought would have horrified me. Thus, I devised my own pictorial language for everything, Hell, Dante, Virgil, boats, dead souls, the whole thing. For the funnel cone of the Inferno that Dante and Virgil descend into — seeing ever more evil sinners and increasingly hideous punishments — I used an upside-down triangle. Above it was always a small upward-facing triangle symbolizing the Mount of Joy that Dante tried unsuccessfully to climb toward to avoid Hell.

III.

On the outside things were great. On the inside I was in agony, terrified, afraid of failing, anxious about what to do next and how to do it. I started not working for longer and longer periods. Hiding it. Then not hiding it. Until all I had left was calling myself an artist. At 27, I had what I think of as a one-year walking nervous breakdown. Which was shattering. I began having panic attacks; couldn’t be around people even though I was dying to be around them; got insomnia, took five-hour walks to wear myself down, was filled with bitter envy for everyone and everything. In this state of self-deprecating deprivation, I wanted what others had, hated anyone who had more space, time, money, education, a better career. To this day I tell all young artists to make an enemy of envy or else it will eat you alive. Like it did me.

When I arrived in New York in 1980 to become part of that world, I didn’t know what hit me or how much of the deep content in my art had to do with Chicago, my own naïveté, and isolation. I was so out of step. Chicago was still involved with 1970s Conceptualism, straight photography, regional ideas of hard-edged abstraction, process art, and Pluralism. Things in New York were so different: The city was exploding in Neo-Expressionism, Pictures, and graffiti art. The first of these was out of my painterly and scale reach; the second, out of my intellectual depth; the last was nothing I was involved with, and I could never stay up late enough or do enough drugs to really participate in clubbing.

I was in shock, unable to muster what real artists use to fortify themselves when faced with situations like this. When I teach today, I often judge young artists based on whether I think they have the character necessary to solve the inevitable problems in their work. I didn’t. I also didn’t understand how to respond to an outer world out of step with my inner life without retreating into total despair. Oscar Wilde said, “Without the critical faculty, there is no artistic creation at all.” Artists have to be self-critical enough not to just attack everything they do. I had self-doubt but not a real self-critical facility; instead I indiscriminately loved or hated everything I did. Instead of gearing up and fighting back, I gave in and got out.

But I learned so much about being a critic.

Artists often complain that critics are animated by resentment. Most of the time, I don’t think they are, but having been an artist, I understand the feeling. Which is why, whatever my flaws as a critic, I have always tried to be as generous toward the people making the work as I would have wanted anyone studying mine to be. I want my criticism to reflect the hell I went through as an artist — to look, even with work I do not appreciate at first blush, for the sign of the soul yelping at me from within or behind. I believe that every artist means everything they’re doing, that no one is making art just to make money or pull the wool over people’s eyes. All artists may want to make money and be loved, but at base they are still serious about their art. That’s why I hate the cynicism that now permeates the art world — all the money and glamour can make it hard to see, and sometimes even harder to believe, that artists mean everything they do as powerfully as anything they’ve ever meant in their entire lives. Jeff Koons is as earnest in his Howdy Doody–Teletubby way as Francesca Woodman and Francis Bacon. That’s part of what makes his great work great, that willingness to fail so flamboyantly!

Outsiders often see the art world as a fashionable never-ending party, buffered from reality by money. Having been an artist, I see it very differently. I see myself as part of this great broken beautiful art-world family of gypsies, searching and yearning and in pain — and under pressure, doing things that they have to do. I refuse to believe this spirit has left the art world even though I comprehend that this exquisite internal essence is now buried under loads of external bullshit. I know almost every artist wakes up at 3 a.m. in a cold sweat thinking that the bottom has fallen out of their work. That each of us is self-taught and some kind of outsider. I want to celebrate, examine, describe, and judge this otherness, outsiderness, and try to see if an artist’s vision is singular, surprising, and energized in its own original way. My vision wasn’t, at least in ways I was able to realize in those 10 or 12 years. I didn’t have the ability and fortitude. That’s why I always look for it in others — root for it in others — even when the work is ugly or idiotic. I want every artist, good and bad, to clear away the demons that stopped me, feel empowered, and be able to make their own work so we can see the “real” them. It’s why I look hard at every artist, at the well-known and the rich as well as the late bloomers, bottom-feeders, outsiders, and eccentrics. Since it’s nearly a miracle that I finally ended up in the art world as a critic — something I never wanted to be — I want every artist to have a shot, to see that power, access, and agency is in their hands. It’s why I value clarity and accessibility in criticism over all the jargon we usually get. I want critics to be as radically vulnerable in their work as I know artists are in theirs.

Being an artist also made me realize that I wasn’t built for the type of loneliness that comes from art. Art is slow, physical, resistant, material-based, and involves an ongoing commitment to doing the same thing differently over and over again in the studio. As my wife, Roberta Smith, the co–chief art critic at the New York Times, has said many times, “Being a weekly critic is like performing live onstage.” Every week. I love and live for that jolt. Criticism involves constant change, drama, information coming in from the outside, processing it in the moment in front of everyone, always being in the here and now while also trying to access history and experience. H. L. Mencken is quoted, describing his own work, as saying it’s best when “it’s written in heat and printed at once.” That’s what I want, what I need, who I am. I have a tropism toward reaction.

I can’t only dance naked in private. I have to dance naked in public. A lot.

IV.

How deep is my lack of artistic character? Pretty deep, it turns out. After I hadn’t seen my art for 30 years and had assumed that it was gone, amazingly, three portfolios of my work surfaced as I was writing this article. No altarpieces. But around 700 drawings somehow survived. And within one extraordinary day three weeks ago, I relived a perfect repeat of my entire artistic journey. I went through these newly discovered portfolios. One by one. Drawing by drawing. I studied them all. I knew almost every one by heart; the ones I didn’t remember were revelations to me. I knew what every move and mark meant. My breath was taken away. I fell madly in love with my work. I was astonished at how beautiful much of it was. How it all made sense. I thought, These are fabulous! I was a great artist. I looked and looked. I was stunned. There were tears of joy in my eyes. Relief.

Soon, I went to get Roberta. I told her the news and asked her to come see. She came into my office and started looking. For a long time. Longer than I had. One by one. Studying, not saying a word. After a while she turned to me and said, “They’re okay.” Stricken, I said, “Okay?! What do you mean ‘okay’? I think they’re beautiful. Aren’t they great?” She turned back to the drawings, looked a little longer, and finally said, “They’re generic. And impersonal. No one would know what these are about. And what’s with the triangles? Are they supposed to be women?” I shot back, “No! They’re Hell!” She talked about how many artists “never get better than their first work.” And just like that, I was right back to where I was when I quit: crushed, in crisis, frozen, panicky.

Looking at it now, I understand Roberta’s reaction. A number of other Wilde ideas apply here. He wrote that art that’s too obvious, that we “know too quickly,” that is “too intelligible,” fails. “The one thing not worth looking at is the obvious.” This sort of art tells you everything in an instant and can only tell you the same thing forever. My work had the opposite problem. It was vague, arcane, and therefore obsolete. Only I could decipher it.

Wilde also wrote that “the vague is always repellent.” My work was “generic” and “impersonal” because of the 1970s post-minimal ways I was working. I wanted to transcend memories, achieve accessible complexity, and enter history from the side. Instead, my art might be able to produce flashes of beauty but couldn’t gain emotional traction; create depth, mystery; impart its secrets, ironies, drama, or cross the threshold of history. I was blinded by the rules I made.

I used to tell myself that I wanted every decision that I made in my work to be about beauty. Baudelaire believed that beauty had two parts. First, timelessness — like the form of a Grecian urn. The other part of beauty is something absolutely fleeting, like a fashionable dandy on the street. My work had something of the timeless beauty of older geometries and hermetic diagrams and illustration. The colors were pretty. But my art didn’t have the look and feel of my own time. Yet I meant it with all my heart. Which was another problem. At that dawn of our age of irony, I was totally sincere. Wilde has something to say about this, too. “All bad poetry,” he wrote, “springs from genuine feeling … It is with the best intentions that the worst work is done.” Of course, he also wrote, “Criticism demands infinitely more cultivation than creation does.” Boom! Let’s fight about that in public.

*This article appears in the April 17, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.