April is John Ridley month, at least when it comes to politically unflinching television. The writer-director currently has his anthology series American Crime airing on ABC (this season focuses on migrant farm workers); on April 16 he’ll see the debut of Guerrilla, a six-part Showtime mini-series he wrote and directed about radicals in 1971 London and starring Freida Pinto, Babou Ceesay, and Idris Elba; then on April 28 Ridley’s Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982–1992, the documentary he directed about the incidents surrounding the Rodney King riots, will air on ABC.

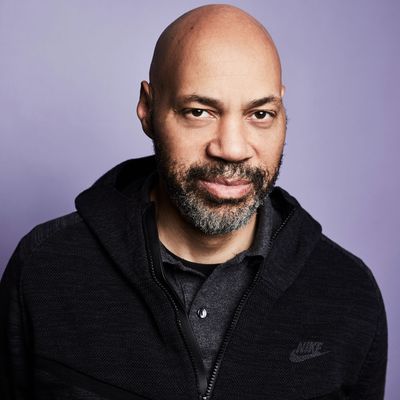

Taking time out from a well-earned family vacation, the 51-year-old Wisconsin native, who won an Oscar for his 12 Years a Slave screenplay, talked about how politics does and doesn’t inform his work, recent controversies over whitewashing, and TV’s power to break through culture bubbles.

What does it mean that, given where our country’s politics are, Hollywood is at a place where the stories you want to tell are stories that networks and studios are willing to finance? Is that something to be optimistic about?

Yes and no. American Crime was something I got invited to do. It could’ve been somebody else that got that call. But look, 12 Years was an independent film. I don’t want to bag on Hollywood, but I don’t think people sit around the studios and saying, “We’ve gotta do more socially aware films.” The contemporary movie audience for socially aware stories hasn’t been cultivated the way the TV audience has. Because TV has so many more platforms, it’s gotten good at doing different kinds of things. The movie business hasn’t. Movies like Moonlight or Spotlight are not the norm.

To immediately undercut the nod I just made toward optimism: Is it disheartening to see that the fights at the heart of Let It Fall and Guerrilla are still the fights of today?

Despite the things I put in front of people, I am an optimistic person. I could not be sitting here talking to you if we were not a progressive country. Look at the bathroom bill in North Carolina: Five years ago, would as many people have been outraged about an affront to transgender rights? But the fact that there are so many things in my projects that invite direct comparisons to what’s going on now was not intended. As a writer, it’s good to feel like you’re on top of what’s happening; as a person, it doesn’t feel good to see that the conflicts of 25 or 45 years ago are so closely aligned with what we’re facing now.

At one point you were working on trying to tell the story of the L.A. riots as fiction. Why revisit it as a documentary?

Yeah, so more than ten years ago, Spike Lee had called me and asked me about doing a film about the L.A. riots. And what happened was that you realize how big and expansive the story is; it can certainly be done as a feature narrative, but there’s not one protagonist, the people in it are not simple heroes or villains, there’s not a happy ending. So it’s a rough proposition to go to a studio and try and get X millions of dollars to tell that kind of story. But with the documentary, ABC came to me knowing that the the 25th anniversary of the riots was coming up. What they didn’t know was that I already had a sense of the narrative.

What parts of that story were left to be told? I think it’s fair to say that the L.A. riots weren’t exactly an under-examined event.

A lot of people think that the L.A. riots started with Rodney King and ended with Reginald Denny; that there was an attack and there was retribution and that was it. But you can see the seeds of the uprising being planted much earlier, from the end of the chokehold era, to the ’84 Olympics, to Sherm Alley, to the Karen Toshima shooting: There were a series of interconnected events, links in a chain, that led to 1992. The more I learned about it, the more it become a story I wanted to tell.

Does the reality of Trumpism affect what kind of stories you want to tell moving forward?

Quadrennial elections or midterms are not going to change my approach or what matters to me. How I feel about what’s going on in this country is secondary to the stories I’m telling. If Trump hadn’t been elected, I still would’ve done the documentary, I still would’ve done Guerrilla.

What matters to you?

The thing that I want to do more than anything else is represent: both in front of the camera and behind it. I owe every good thing I have to Hollywood, but there’s a lack of representation of traditionally disenfranchised people. Whitewashing is still a real problem. 2016 was a strong year for film and people of color, but if you think Moonlight winning Best Picture means the future is necessarily going to be better, then you’re looking at the future through a straw.

What do you see as other major problems in the business?

In the world, straight white men are the minority, but people talk about “diversity” as if that isn’t the case. Does it really make sense that the prevailing attitude toward “diversity” in Hollywood involves making us sidekicks? I don’t expect that every show is going to have a one-to-one white to person of color ratio, but on balance we can do better. It’s painful when you see films that are not representing, that are strip-mining cultures, that are taking people of color out of material. Fighting against that is a daily struggle.

On the subject of whitewashing, I assume you’re aware of the Ghost in the Shell controversy. What do you think of the, I guess plausible, argument that it’s naïvely idealistic to believe that movie would’ve gotten financed with anyone other than Scarlett Johansson as its star?

If someone says Ghost in the Shell only gets made with Scarlett Johansson as the star — and there’s no two ways about it: she is a star, and a supremely talented one — they’re just making an excuse. You’re putting her in a space where you could instead be helping make an Asian or Asian-American star. So when you say, “No, we’re never going to take that kind of chance,” then you’re in the realm of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Plenty of movies starring white people fail, but they keep getting opportunities. And there are films like Get Out, which wasn’t even really star-driven, that made a huge profit. Why shouldn’t that be the model? I’ve been unbelievably fortunate in my career, but there are times when I look at something like Ghost in the Shell and think, How much longer can this last?

So the crass business logic I was talking about just doesn’t hold up?

I don’t think it does. A Japanese comic is already a global property. Is the best way of enhancing that brand really to put a white person in it? Why is that always the answer? Or Iron Fist: The reason for not casting an Asian-American is because the creators were staying true to the original comic? So why is it so important to stay true to the comic in that case but not in the case of Ghost in the Shell? I really have a problem when people aren’t straight about this. If someone would just say, “This decision is about the money,” I’d have more respect for that than I do for people pretending to represent a diverse global world but only so long as it revolves around anglicized ideas of diversity. “The finances, the source material” — stop with the excuses. I understand that saying this stuff comes at the risk of offending talented people who I’d want to work with, but I gotta take that risk. We can’t just sit around and not talk about these things.

Do you ever feel that the discussions about things like cultural appropriation can be creatively restricting? Do studios stay away from trying to make movies that deal with culturally sensitive topics because they’re too scared of potential backlash?

I understand those concerns. If in 2017 you hear there’s a movie about black American history and a white dude is involved, you’re like, huh? But then you think, It’s American history, not just black American history. For me the bigger trap is thinking, Okay, we gotta get a Hispanic director for a movie about Hispanics, but then not considering that same director for an action movie set in New York. I can live with a white dude directing the Jackie Robinson film or Hidden Figures, both of which were really pretty good. But do I get to do Star Trek? Is someone going to think of me for a project that has nothing to do with race. It’s great if a woman [Patty Jenkins] gets to direct Wonder Woman but we also need to make sure she’s in the mix to direct a movie about a platoon of men fighting in Vietnam. That’s where we need to be.

What would the response be from the big studios if you pitched them a romantic comedy set in hipster New York starring two white people?

At this point in my career, the first response would be “That’s really interesting, John.” Then they’d say, “How much is that going to cost? Can you get some of your famous friends in it?” I would have a shot at getting that romantic comedy made, but only because I understand how to maneuver to a place where I’d have a higher chance of it happening than the average person would. I can’t get a movie made on my name alone.

Are there practical, systemic things that can change in Hollywood to address representation? Or is it ultimately a matter of individuals choosing to do things differently?

Hollywood is no different than the airline industry or the hotel industry: There are people in power who have blind spots. I’m sure you could go through my business — I have a company now — and say I’m not representative of so and so. But I do think it’s about being aware that you’re falling short. And doing better with representation should not be a mandate for the cultural good, it should be done because the people getting overlooked are talented and deserve opportunities. Look at Moonlight or Lion; pick a film that represents. The quality does not fall off. The biggest difference between Hollywood and other industries is that its mandate is to represent the world. That’s why it’s irresponsible to default to a “normalcy” that centers on straight and white when that’s just not the way the world looks.

Do you have confidence that the kind of entertainment you’re talking about — that’s realistic about race, for example — is capable of affecting audiences who aren’t inclined to think sympathetically about the issues that are important to you? Or maybe the simple way of asking that question is this: Do you think anyone who supports a border wall is watching American Crime?

You’re talking about the audience fractionalizing. Here’s the good part about that: Shows that have a small overall audience can still achieve cultural density. Take Transparent: In the context of the country, very few people watch it. But that show has undeniably affected the cultural awareness of what it means to transition. Maybe people haven’t seen Transparent, but they know the conversation about it, and that means when we’re talking about the bathroom bill, transgender people aren’t just “Oh, those odd people.” There’s awareness because of that show. So sure, there are tons of people who aren’t interested in watching 12 Years a Slave or American Crime, but the people involved in making them wind up on talk shows, they pop up in commercials and at award shows — you can’t ignore this stuff. You can enjoy it or deal with it but you can’t ignore it. That’s how I look at what I do generally — you enjoy it or you have to deal with it.

You had a disheartening experience earlier in your career where an executive asked you to change the race of a character you’d written from black to white. At this point in your career, are you still having those kinds of conversations?

At the development stage, I’m not encountering that anymore. I’m not necessarily a big moneymaker, but I think people realize there’s value in the kinds of stories I’m trying to tell. I have a deal with ABC, and Disney has an entire world they’re telling stories to, not just America. Look, it’s all about people in charge having the guts to say, “We gotta point towards the North Star.” Because it matters. For me, as an example, going to see Star Wars with John Boyega and Daisy Ridley — I loved Star Wars as a child, but it’s a whole different feeling to bring your kids to the new Star Wars when you’re a person of color. The enjoyment is so much more relaxed when you see yourself represented up there onscreen.

Totally randomly: What are you reading now?

I’ve been reading Rick Perlstein’s Invisible Bridge. It’s about the downfall of Nixon and the rise of Reagan. You gotta read it; it’s everything we’re going through now, then. It’s very calming, because it gives this sense of we’ve been through this before. The rollbacks of that era were real, but progress remained.

I’m pretty desperate for any cultural recommendations that could be described as “calming” given the political hysteria I’m feeling these days, so thank you for that.

Yeah, the book really shows that what we’re about as a nation is stronger than presidential politics. It’s so good. His Nixonland is unbelievable, too.

What’s the thing you most want to make next?

The next things you’ll see from me are going to be my responses to Doctor Strange or Ghost in the Shell. I’d like to take the things I believe in morally and politically and put them in a more fantastic space. There’s a graphic-novel series I did ten years ago and now I’m going to do a second series. It’s set in the 1970s; it’s very Guerrilla-like in some ways, but with superpowers. Politics is a whole other thing when you’ve got heat vision.

This interview has been edited and condensed.