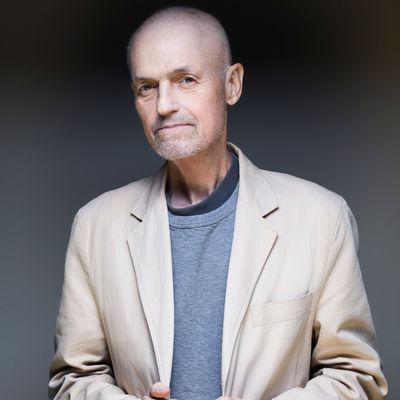

Jonathan Demme, one of the American cinema’s finest, most insistently humanist directors, has died at the absurdly young age of 73, from complications of throat cancer and heart disease.

It’s hard to imagine New York or the world or the movies without Demme in the house. How do you eulogize someone whose overriding aspect is aliveness?

I guess you start by simply naming some of his wonderful movies, in chronological order: Caged Heat, Handle With Care, Melvin and Howard, Swing Shift, Stop Making Sense, Something Wild, Married to the Mob, The Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia, Beloved, Rachel Getting Married, Neil Young: Heart of Gold, A Master Builder … Those are my favorites, but many of the others are vital, too — Swimming to Cambodia, Cousin Bobby, his Haitian documentaries, his brave and urgent remake of The Manchurian Candidate, his patchy but exuberant Ricki and the Flash …

In 2002, I wrote an article about Demme for the New York Times in connection with his loose remake of Charade, The Truth About Charlie — a difficult piece because the movie was plainly a dud. It was, however, a generous and overflowing dud, and an excellent prism through which to view the man the Times’ headline writer called “the Happy Hipster of Film.” For one thing, Demme’s camera was always swerving off the main actors to catch street performers or passersby or people he knew.

“There seem to be no extras,” I wrote, “only characters from movies yet to be made … Mr. Demme tries to cram in the maximum amount of life per square inch of movie screen.” (The “Mr.” thing is Times style and is reproduced accordingly.)

“Other faces that show up in Mr. Demme’s films are from his vast circle of acquaintances, business associates and creative influences – so that watching his movies is like looking through a scrapbook of his life. In The Truth About Charlie, Mr. Demme not only salutes Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player (1960) with an excerpt; he brings in its star, Charles Aznavour, to serenade the lovers.

“Shoot the Piano Player, he says, was one of the first movies he reviewed for the student newspaper at the University of Florida at Gainesville in 1965, after he flunked out of pre-veterinary chemistry classes. Rather than slink back to Long Island (he was born in Rockville Centre), he stayed in Florida and became a critic so that he could see movies free of charge.

“I remember the moment when a gangster tailing Aznavour tells a cop, ‘If I’m lying may my mother fall dead’ – and Truffaut cuts to the old lady clutching her chest and collapsing on the floor and then goes back to the scene,” Mr. Demme recalls. ”I mean, talk about movie magic! It was my introduction to a whole other dimension of movies.”

Two years later, while working as a publicist, Mr. Demme had the job of escorting Truffaut around New York while he was promoting his Hitchcockian thriller The Bride Wore Black (1967). At the end of the week Mr. Demme asked Mr. Truffaut to autograph his 1967 book of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock.

”You’ve got to see this,” says Mr. Demme. ”This is so unbelievable.” He pulls the well-worn copy off a shelf in his library and opens to the inscription, which reads: ”Pour John Demme, before his first film, and with mes amitiés. François Truffaut.”

”I said, ‘Um, François, I’m not interested in making my own movies,’ and he said, ‘Oh yes you are.’ ”

Oh, yes he was. After his publicist stint, Demme went to work for exploitation mogul Roger Corman, who let him make Caged Heat, one of the most entertaining films in the depraved women-in-prison subgenre — and one of the few to challenge the male viewer’s voyeurism by making the villain, a prison guard, a voyeur.

But his first real “Demme” film was the ensemble comedy Handle With Care (also called Citizen’s Band), from a witty script by Paul Brickman that centered on people using CB radios as a way to escape their loneliness and, in some cases, to assume personalities much different than their own. On display was Demme’s enthusiasm for what could be snidely called kitsch but more fondly folk culture, and for the ways in which people sought and achieved transcendence through such disreputable (in some circles) means. Demme loved everyone, even the screw-ups and philanderers. It was a film with no real villains. Maybe that’s why his stab at a “Hitchcock movie,” The Last Embrace, was almost as bad as Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black. Hitchcock’s peculiar brand of determinism — which worked jolly well for Hitch — hems in more humanistic directors. Demme quickly learned that he was better at exploring relationships than constructing flashy thriller set pieces.

But Demme struck gold with Bo Goldman’s script for Melvin and Howard, a sympathetic meditation on the American dream of getting rich quick. He found in Howard Hughes (Jason Robards) a grizzled, pathetic figure whose longing for true connection was worthy of myth, and in Melvin Dummar (Paul Le Mat, also in Handle With Care) a man worth believing — whether or not what he told was the truth. It should have been the truth! Meanwhile, Mary Steenburgen’s spirited stripper nearly sashayed off with the movie.

But actors running away with movies was what Demme wanted — an unusual goal for an auteur. “We’re there to create the safest possible atmosphere, the most nurturing possible atmosphere,” he once told me. “You could have all the wonderful shots and cuts and music and what have you, but if it ain’t happening in the performance, it just ain’t happening.”

After spending a few days watching him rehearse his one and only theatrical production, a critically reviled revival of Beth Henley’s Family Week (I loved it), I opened my New York article with what I meant as the highest praise:

Jonathan Demme began his career in movies as a publicist, and one key to his greatness is that he has never entirely relinquished that role. Forty years later, he is the artist as promoter, the artist as apostle and entrepreneur. The writers he engages, actors he casts, musicians he spotlights, and political figures whose lives he documents, have voices he wants you to hear — passionately. His job is to put them in their most brilliant light. He builds families of artists and lets them take center stage, his own art concealed. When unchecked, his teeming multi-culti humanism can seem overindulgent. But set his vision against a darker one and the alchemy begins.

When I interviewed him onstage after a screening of A Master Builder, I was curious what he thought of that characterization. “I know that if you remove my enthusiasm,” he said, “I’m not sure I have a whole lot left to offer.”

I kick myself for letting that bit of self-effacement pass. I should have said, “Bullshit.”

In 1984, Demme had his first big-star studio vehicle with Swing Shift, which I wish you could see in its original cut. I wish I could see it again. While writing a profile of Christine Lahti for this magazine in 1987, I was slipped a tape of Swing Shift as it stood before it was yanked from Demme and reshaped at the behest of its star, Goldie Hawn. (She was allegedly upset that she and Kurt Russell weren’t sufficiently likable — and that Lahti was stealing the film. Demme told me he was overjoyed when Lahti was nominated for an Oscar.) In his cut, Swing Shift was a feminist epic that was delightfully light on its feet, one part homage to the Rosie the Riveter era in wartime pop culture, the other an intimate portrait of women reshaping that culture. No, I don’t think Demme’s cut will ever see the light of day. Maybe, as Donald Trump once said, the Russians could do something …

Swing Shift was a bad experience (it flopped), but the next project was as good as it gets. Stop Making Sense remains the best of all concert films, both stunningly immediate and gorgeously planned out. Before our eyes, one piece at a time, a band (the Talking Heads and guests) comes together, and the effect is to see it as both a unified (multicultural, utopian) entity and a collection of brilliant individuals. Buy the Blu-Ray and play it as loud as you can on the biggest screen you can find. Demme is so profoundly in tune with David Byrne and the other musicians that you could almost believe the film edited itself — that the cuts to individual players are just going with the flow. (In a sense, they are, but to reach that flow is something else.) The movie itself is both a gentle mockery of the (white) American Dream and a celebration of transcendence. But there’s beauty in that absurd dream and satire in that notion of transcendence. Stop Making Sense is a postmodern masterpiece.

With Stop Making Sense, Demme had found his rhythm. His next fictional film was one of his biggest flops and also one of his best — I’d rank it, along with Melvin and Howard and Stop Making Sense, as one of the finest American movies of the ’80s. Something Wild, from a witty script by E. Max Frye (where is he now?), is a kinky screwball comedy that grows progressively darker, as a New York yuppie (Jeff Daniels) becomes an amused tourist in Middle America — and then, gradually, a participant in a grim story of domestic abuse. A few foolish critics complained that the movie became too dark, that it was better when set on the border between funny and creepy. I was one of those fools. Because the last section is perfect as it is. The death of the so-called bad guy is staged and acted in a way that’s both a relief and breaks your heart.

Maybe Demme listened too hard to us idiots because his next movie, Married to the Mob, stayed funny all the way through and is — despite its many felicities — a minor work. The big one — the most atypical but by far the most famous — was Silence of the Lambs.

Think about this for a second: a humanist tackling one of the most grotesque serial killer narratives up to that time. But he shows no relish for the Grand Guignol. His tone is mournful — he seems as frightened of Hannibal Lecter as his heroine, Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster). This is really the story of a gravely damaged young woman who finds the strength to save other young women — by whatever means necessary, including accepting a mentor who psychologically rapes her.

The larger tension in Silence of the Lambs comes from a director who’s trying to find meaning in gruesome material — and not always succeeding. However you slice it, it’s a horror movie. Demme and the novelist Thomas Harris were bound to part ways. In Harris’s sequel, Hannibal, Lecter was a co-hero, a vigilante who only killed the “rude — free-range rude.”

From my Times article:

“The Silence of the Lambs” made his name in Hollywood, but it is a mark of his ambivalence about its brutality that he was unwilling to sign onto ”Hannibal” (2001), the Grand Guignol circus that was its sequel… He speaks of the young F.B.I. agent Clarice Starling (played in “Silence” by Jodie Foster) the way one might of a family member who has met with a terrible accident.

“If you can be in love with fictional characters, I’m in love with Clarice Starling,” he says. ”And I was really heartbroken to see what became of her during that passage of her life in ‘Hannibal.’ I have a funny feeling that Tom Harris may feel like our culture has become so corrupt that someone with Clarice’s qualities is doomed to fall from grace. There was no way I could go along on that journey.”

Demme was also beginning to pull back from violence onscreen.

“That exchange of gunfire at the end [of Silence of the Lambs] between Jodie and the killer, Jame Gumb, is clumsy, and blunt, and brutal. It was presented in such a way to make absolutely sure that the audience wouldn’t cheer because that gun went off and killed Jame Gumb.

”The little boy in me can still find pleasure in excitingly presented gunplay in movies, so I’m not judging anybody else’s use of guns,” he says. ”But it’s tricky. If guns in our culture are a problem – and I think they are – is using them so much and making gunplay so entertaining part of that problem? It’s certainly not part of the solution.”

When Demme accepted the Oscar for The Silence of the Lambs, he talked mainly about the crumbling of its studio, Orion Pictures — a tremulous speech that was a tad fulsome but nonetheless showed who he was: a man in mourning for the death of a welcoming home for artists.

There was another awkward bit of fallout from The Silence of the Lambs: angry gay protests over the transvestite psychopath. Demme’s first thought was for the actor, Ted Levine, whose bravery he publicly defended. But he met with activists and took what they said to heart. The AIDS drama Philadelphia, with its explicit plea for tolerance, came after the documentary about Demme’s social-activist cousin, Cousin Bobby, and won Tom Hanks his first Oscar. Next came the Toni Morrison adaptation Beloved, which is ripe for reevaluation. Demme believed that Disney pulled the film too quickly from theaters but conceded to me that it had too much of an element of, “This is good for you, take your medicine … We might have scared people off.”

After the flop of The Truth About Charlie, Demme took on a clearly thankless task: remaking — really, updating — John Frankenheimer and George Axelrod’s brilliant adaptation of Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate. It was not a critical or commercial success but the film deserved better. It wasn’t some meaningless retread. It was made at an especially bleak moment in the Iraq occupation and “Manchuria” became the “Manchurian Corporation,” loosely modeled on Halliburton. It was a cry of pain in the face of moral confusion and anger at being misled. It was vital.

It was also an ordeal. As he told me:

“It was such a hassle, the studio and the producers and the … oh God … I said, enough with the fiction already. I’m perfectly happy to do documentaries and performance films.” But then he got Jenny Lumet’s script for Rachel Getting Married and decided to make it in a different way: “I finally achieved a zero rehearsal mode!”

In this story of a young addict (Anne Hathaway) who comes home for her sister’s wedding, Demme virtually threw his performers in front of the camera and told them to go for it, and the upshot was messy and alive, hectic but always emotionally focused. Some critics jeered at the film’s last sequence, a wedding concert that goes on and on. I knew why Demme wanted it, though. He needed the celebratory communal interlude to offset the central story, which was bleak and ragged and unfinished.

Demme never stopped working, though some of his dream projects never got made. (I know he wanted a crack at the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and wish he’d gotten it.) His theater production didn’t work out too well, but he did a bang-up job stepping into the shoes of the late Louis Malle and bringing Andre Gregory’s production of A Master Builder to the screen (quickly, for almost no money). His last fictional feature, Ricki and the Flash (from a script by Diablo Cody), didn’t really work, but it had its charms. He told me he had a blast making it, with all that music in the studio. As I listened to him, I was reminded what cinematographer Tak Fujimoto told me about the atmosphere on Demme’s sets. I asked him whether Demme — a believer in the spirit world and in the notion of karma — couldn’t bear the thought of bad feelings infusing the celluloid. “There wouldn’t be bad feelings,” he responded. “It couldn’t happen. He would stop shooting.”

In January, Demme was a guest at the annual New York Film Critics Circle awards dinner, where he presented the directing prize to Barry Jenkins for Moonlight. He fairly bounded onto the stage. He looked healthy. (He had recently finished his Justin Timberlake documentary, which I haven’t seen but hear is good.) Demme never seemed happier than when praising other directors. In fact, before presenting the award, he reeled off five or so movies that he wished the critics could have honored, too.

Jonathan Demme was one of cinema’s most contagious enthusiasts. I can’t believe I’ll never bump into him again in line for a movie and hear about some musician or filmmaker whose work I have to see or hear. I thought he’d always be around — or in Haiti, which he loved, or documenting a real-life hero or heroine, or traveling with a musician and trying to catch his or her essence on film. His loss is momentous. But I’d like to take a page out of his book (and Star Wars) and hope that his benevolent spirit will watch over our movies, more powerful than ever, reminding us that where there is art, there is hope.