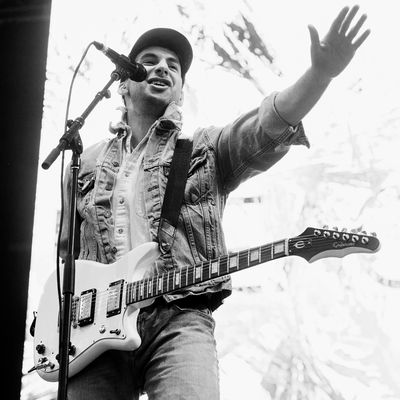

When I was first presented with the idea for this story — where I would explain how to write a perfect pop song — I told my manager, ‘It’s a cool idea, but it doesn’t make any sense. There’s no one way to do it.’ But as I was describing why I couldn’t do it, I was also asking myself questions, and those questions made me come around. The big question is this: What is a pop song? The easiest way I can describe what makes a pop song a pop song is that it’s a song you want to hear over and over. Some people will instantly think, Well, that means it’s simple and stupid. The truth is that it’s the opposite. What song have you played 10,000 times? It’s probably not something basic. It’s probably a song that validates your experience on Earth. For me, a perfect pop song is something like ‘This Year,’ by the Mountain Goats. That’s a song that talks about alcoholism, domestic abuse — experiences I’ve never had — and ties it all together in the chorus by saying, ‘I’m gonna make it through this year / If it kills me.’ That chorus speaks to me. It makes me feel like the song was written for me. And I’ve heard and written enough songs in my life to know which ones, like ‘This Year,’ have that ability to connect. How you try and make a song like that is something I think I can talk about.

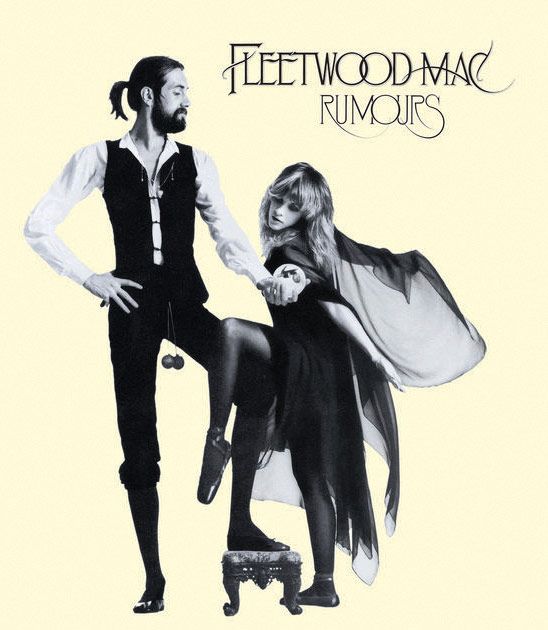

What you’re trying to create with a perfect pop song is a song that doesn’t sacrifice emotion and energy and smarts and still reaches people. Michael Jackson’s ‘Black or White,’ Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, Prince’s music: material that connected a ton of people and was brilliant. Or, for a more modern example, there’s ‘Alright,’ by Kendrick Lamar. There is nothing not intelligent about that song, and it’s the biggest hit. If you assume people want dumbed-down music, the result is dumbed down. If you assume people are smart, you get moments of brilliance.

Once you understand that listeners want to be challenged, then you also understand that you can’t take shortcuts. In my studio I don’t use sounds that replicate better sounds. If someone tells me there’s a new soft-synth that’s supposed to sound like a Moog, instead of settling for that I’ll try and get a real Moog. The average listener doesn’t know that there’s a difference between the low end of an old Mini-Moog Model D and some computer trying to mimic that sound, but they do recognize a difference in feeling. A perfect pop song is made up of perfect elements. You can’t fake any part of it. The whole thing has to be a masterpiece.

So how do you do it? It helps to have a big songwriting concept. Anything I’ve done that I felt was great started with a big concept. Bleachers’ single right now is a song called ‘Don’t Take the Money,’ and the title is a phrase I’ve been saying for a long time. It means follow the light, follow your gut, don’t sell out. So I started with that concept, because the song is not a melody; the song is about ‘Don’t Take the Money.’ You start with the concept and build from there, whether it’s a beat or a guitar part. For ‘Don’t Take the Money,’ my first thought after the concept was that I wanted the guitar part to be a chime-y Jeff Lynne thing. I wound up using an electric sitar. I was at a friend’s house using one and thought it was cool, then I bought one and gave it a certain kind of compression — a Chris Lord-Alge vocal plug-in but used on the electric sitar. Doing that is technically incorrect, but it allowed me to find the sound I didn’t even know I was looking for. What does that mean? It means when you’ve stumbled on something that gives you the gut feeling of having nailed it, you have to be able to recognize that feeling, say ‘That’s it,’ then move on. Then you start thinking, What’s next? What should happen in the pre-chorus? How do we make it more exciting? Your mind just starts moving.

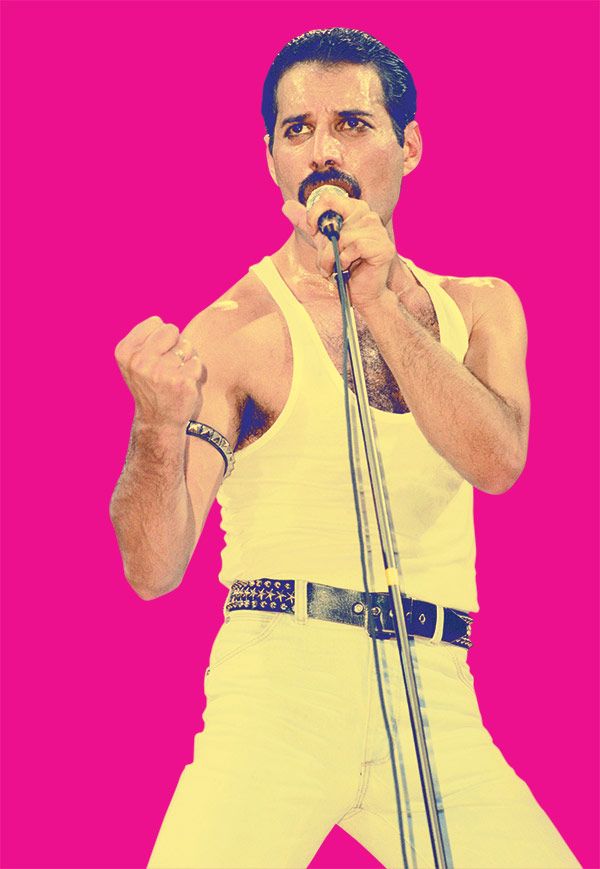

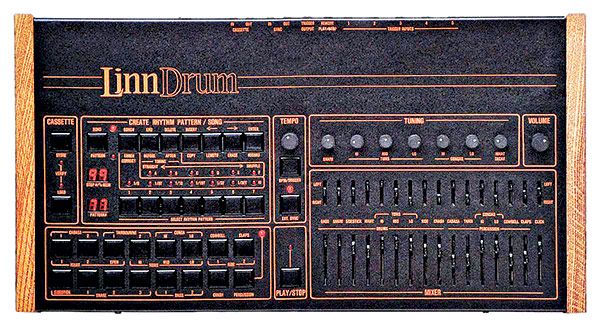

Let’s get into the drums. When I was recording ‘Don’t Take the Money,’ the idea for the drum sound came from watching a YouTube video of Queen playing ‘Radio Ga Ga’ at Live Aid. Those drums sounded bigger, better, and more bombastic than I’ve been hearing lately. What was going on there? Well, Queen was using a Linn drum. So I went home and bought a Linn drum and started messing around. The whole drum part to ‘Don’t Take the Money’ is made with a Linn hi-hat, a Linn snare, and a Linn kick. Then I ran it through an old Binson tape-echo machine until boom — I got to the ‘Oh, that’s it’ moment. You’re just constantly looking for sounds that create those gut feelings.

Getting that feeling is everything, and there’s no set path to finding it — which is why I was initially hesitant about this piece. The whole point is that there’s no path. Instead, the thrilling thing about making a pop song is that it’s like you’re on the beach with a metal detector, trying to gather gems — or realizing that you’ve overlooked one. Let me give you an example of what I mean. There’s a song on the Bleachers’ album [Gone Now] called ‘Hate That You Know Me.’ It’s about being with another person and how you hate that they know you, because sometimes it’s so much easier to be alone with your problems. I’d made a super-fun track that I was excited about. But I started to play the song for people and all they’d say was, ‘That’s cool.’ Nothing more. Something wasn’t working. Writing and recording is like making food: You could have perfect ingredients, but too much salt and the whole thing tastes like shit. So I kept looking at the song and figured out there was an issue with the vocal take. I had this tight reverb on the vocal. I took that reverb off, started playing the song for people again, and right away they were listening to the lyric more intensely and they fully got it. A decision that simple, about reverb, can make the vocal feel like it’s being sung two feet away from you or you’re inside the singer’s throat. Something like reverb makes an emotional difference. All your aesthetic choices have to depend on your concept for the song. Then the production and recording are supposed to serve that vision.

Serving your vision can be a kind of quicksand, though. A common problem is when you get attached to something because of how it happened instead of how it sounds. It’s taken me my whole life to understand that you can’t emphasize your process at the expense of the final result. All that matters is if that result speaks to people, because that’s the whole point of a great pop song.

Everything I’m saying about connecting emotionally applies to the lyrics too. I always begin from Bruce Springsteen’s strategy of writing lyrics that are blues in the verse and gospel in the chorus. So in ‘I Wanna Get Better,’ in the verses, I’m talking about death in my family and 9/11. But then the chorus goes a little broader: ‘You know that this isn’t a joke to me.’ You invite people in with your honesty and then deliver something for everyone. That’s why I talk so much in my lyrics about my sister’s death and my depression and anxiety. It’s about creating mutual trust. It’s like in that Mountain Goats song I was talking about, ‘This Year.’ No, my stepfather didn’t beat my mother and I never dealt with alcoholism, but, yes, I’m gonna make it through this fucking year if it kills me. The honesty in the songwriting goes both ways. Being able to create that feeling is the mark of a true pop artist.

Speaking of Springsteen, the Juno-6 keyboard, the very basic pad sound, the sad thing that sounds a lot like Springsteen’s ‘Streets of Philadelphia’ — I use that all the time. I know I’ve been saying there are no rules, but I do fall back on the Juno-6. That sound is my musical soul. It hasn’t failed me yet when I want to twist the knife into your heart just a little bit. It doesn’t have a perfect sound, but it feels human.

Once you get to the postproduction stage, the mixing and mastering, you’re looking for the right sonic representation of what you originally set out to do. You have to be listening and asking yourself, What parts lose you? Do you feel enough of the beat? Where do you feel it? In your gut? In your shoulders? Where do you want people to feel it? Does the lyric speak to you? Is the take and tone of the vocal what you want it to be? Is there too much high end? Is it too filtered and not present enough? You have to be insanely vigilant and also maintain a part of you that’s more objective. Balancing those approaches is the only way you get great at this kind of work. And at some point you’re going to have to play back the mixes on your phone, just to get a sense of how the track is going to sound to people out there in the world.

How I go about making pop music is the same whether I’m writing for Bleachers or writing with Taylor Swift or Lorde. You just focus on doing something that matters. A lot of people in the industry will hear an amazing demo that has magic in it and then say, ‘This is great, now let’s do it for real.’ What’s real is the thing you just heard! Things don’t often end up better after they go through the industry wheel. You can’t use metrics and songwriting math to catch lightning in a bottle. And the hard work of trying to catch that lightning is what I live for. That’s actually the sick truth behind all this: How do you write great music? You sit in a room for your entire life, trying to write great music.

*This article appears in the June 26, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.