For the vast majority of my 31 years on this Earth, I was the only comics reader in my family. I’ve been picking up funnybooks — most of them, I’m slightly ashamed to say, of the superhero variety — for decades and, with the exception of some parental dabbling in NPR-approved works like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, mine has been a solitary pursuit when it comes to my clan.

So when my 10-year-old half-sister and I found ourselves in a bookstore a few months ago, I thought I’d be the cool older brother and see if I could introduce her to the world of sequential art. I grabbed a copy of Raina Telgemeier’s kid-oriented, magical-realist graphic novel Ghosts, and handed it to her. “I’ve got something cool for you to read,” I told her.

She gave me that cluck of the tongue and roll of the eyes that are all too familiar to relatives of children at that age. “Ugh, I’ve already read all of Raina’s books, Abe,” she said.

“All of them?” I countered, thinking she surely couldn’t have consumed every one of the eight tomes Telgemeier has written and drawn — I mean, I’d only read two of them, and I get paid to write about this stuff. But my sis proceeded to list, well, all of them. Hell, she was on track to outpace my lifelong comics habit, as I’d only started picking up comic books at age 11. There’s a new comics connoisseur in the family, and given her appetite, she’s a consumer force to be reckoned with.

Indeed, there’s a whole new influx of those connoisseurs into the family of comic-book readers, and they all look like my sibling. Although the medium began as a killer app marketed to young folks in the 1930s and continued to appeal primarily to folks under 18 for a half-century afterward, comics publishers like Marvel, DC, and an array of smaller firms took a turn toward darker, more adult-oriented material in the mid-1980s. At the time, it was a wise decision: It reduced turnover by holding on to children of the Baby Boom after they might have otherwise tossed the habit aside.

However, by the turn of the millennium, that shift toward the mature became a demographic time bomb. The intended readership was getting older and older, and few young people were replacing them. As Telgemeier put it to me, “You have this industry, comics, that has spent the past few decades fighting so hard to say, ‘We’re not just for kids,’ and it overcorrected to the point where there really wasn’t anything for kids.”

As of today, the average superhero comic relies on the enthusiasm of people well into their adult years, ones who enjoy — or at least tolerate — ever-more-convoluted twists on characters with whom they’re already familiar. Though they make occasional stabs at drawing new readers, Marvel and DC’s business decisions have typically been based on the desires of a veteran core. Sales to those people are decent enough to keep those companies afloat for now, but there’s usually been precious little in the way of vision for how to radically expand the market.

But less than a decade ago, a tectonic shift began — and Marvel and DC had nothing to do with it. Traditional buyers like me had nothing to do with it, either. Indeed, the comics Establishment is only just now starting to play a desperate game of catch-up. That shift was the result of decisions made by librarians, teachers, kids’-book publishers, and people born after the year 2000. Abruptly, the most important sector in the world of sequential art has become graphic novels for young people. Call it the Youth-Comics Explosion. It’s redefining the future of an entire art form.

Although it hasn’t been widely publicized, once you start asking around among people in the know, you find that there’s a total consensus that the explosion is very real. “There’s a huge boom going on, by all means,” says Brian Hibbs, a respected market analyst, columnist, and retailer who owns a pair of stores in San Francisco called Comix Experience. “When you look at BookScan” — Nielsen’s estimates of national sales to bookstores — “the top sellers are pretty much all kid lit, which is pretty fantastic.”

You don’t need to have access to BookScan to see evidence, though. Up until early this year, the New York Times published best-seller lists for comics — and Telgemeier, alone, would regularly have half of all the paperback slots. Executives at Scholastic will tell you that comics fly off the racks at their famed book fairs for young students. According to Milton Griepp of comics-industry analysis site ICv2, aggregated annual comics sales across different kinds of retailers for 2016 revealed that more than half of the top-ten comics franchises were ones aimed at kids. Eva Volin, a librarian based in Alameda, California, told me, “We’re in the middle of a graphic-novel renaissance inasmuch as not only are kids reading comics, but comics are being written for kids.”

As a result, supply is rapidly rising to meet seemingly insatiable demand. DC is hiring for a new division targeted at young readers, and has already done a bit of a stealth launch by publishing youth-friendly takes on their fabled characters like Supergirl: Being Super and DC Super Hero Girls: Finals Crisis. Marvel has built on the surprise mainstream-bookstore success of their young-adult comic Ms. Marvel by introducing more series in that vein, such as The Unstoppable Wasp and Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur. Conventional book publishers are growing their youth-comics investments, comics publishers are doubling down on their production for youths (BOOM! Studios is relishing the ongoing success of its all-ages KaBOOM! line, for example), and kid-specific comics firms are expanding (youth-oriented publisher Papercutz just opened up an imprint for tweens called Charmz).

At a glance, it all makes perfect sense. Why wouldn’t young readers gravitate toward a medium that can so brilliantly mix visuals and text in a way that makes a story relatively easy to digest? And why wouldn’t publishers cater to them? And yet, up until recently, there was a near-total disconnect between kids and comics. Just ten years ago, DC tried to do a young-adult comics line called MINX, but it was shuttered after only a few months. Sources at DC told Comic Book Resources reporter Andy Khouri that “this development should be seen as a depressing indication that a market for alternative young adult comics does not exist in the capacity to support an initiative of this kind, if at all.”

DC was not alone in its frustration. Brigid Alverson, who runs the blog Good Comics for Kids, has been making trips to grade schools to talk to students about comics for 15 years, and struggled in the beginning. “For the first few years, I’d say, ‘Who reads comics?’ and there was always the one kid who read Marvel, two or three who read manga online, and a few Calvin and Hobbes fans, but everyone else was completely unaware of comics,” Alverson says. “In the last few years, it’s gone from kids not knowing about them to clamoring for them. I’ll produce a few of these books and read from them and kids will scramble and fight over them.”

So, what changed? As with all market shifts, the Youth-Comics Explosion can’t be pinned to any singular factor, but there are a few theories about which decisions and individuals triggered the phenomenon.

You can argue that it began with a foreign invasion. “I’d trace a lot of the beginnings of the under-18 market to the manga boom in the early aughts,” says Griepp. Virtually everyone else I spoke to concurred. Manga (the catchall term for Japanese comics) experienced a spike in American interest at the turn of the millennium, powered by the crazes for their stylistically similar cousins in Japanese animation, most notably the cartoons Pokémon and Sailor Moon. In Japan, comics have long been accepted as mainstream literature of the high and low varieties — and readers both old and young consume them.

When manga-oriented American publishers such as Tokyopop — founded in 1997 — set up shop, suddenly, swaths of young people found sequential art that appealed to them. “Japan has a strong tradition of writing and drawing books about magical boys and girls, which is one of the favorite children’s and YA prose genres today,” says Gina Gagliano, marketing chief for youth-targeting comics publisher First Second Books. “When these things were published and brought over to the U.S. for the first time, there were comics that actually echoed the prose books that people could find.”

Manga remained somewhat disdained by the American literary Establishment. However, members of said Establishment began opening their eyes to comics when English-language creators entered their domain in 2002. That year, a group of such creators — including luminaries like Neil Gaiman, Art Spiegelman, and Colleen Doran — were invited to attend the American Library Association’s annual Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) pre-conference gathering. “They expected your normal pre-conference turnout, but the room was packed,” says Volin. “At that conference, librarians officially embraced comics.”

One comics creator at 2002’s YALSA became particularly influential in triggering the Youth-Comics Explosion: Jeff Smith. From 1991 to 2004, Smith had self-published a black-and-white serial comics story called Bone, which followed the kid-friendly adventures of a group of mismatched anthropomorphic bones who journey through a wild fantasy land. It had enjoyed critical acclaim and a solid degree of popularity, but had never become a massive hit in mainstream bookstores. That changed thanks to David Saylor, a longtime executive at children’s-book titan Scholastic. He’d been pondering the notion of publishing graphic novels for kids, but needed something to act as a vanguard in his mission of market change. Bone, it occurred to him, could be that vanguard.

“It was longer-form storytelling, epic storytelling, great narrative, and great artwork,” Saylor recalls. Bone was finishing its long initial publishing run, and Smith was looking for something to do with it next, so Saylor proposed the idea of having Scholastic reprint the whole saga in color and use the company’s considerable market savvy to get it in front of a new audience. Smith agreed, and not only did Scholastic begin publishing the colorized Bone in 2005, Saylor even got the higher-ups to approve the creation of a whole new imprint for comics, called Graphix.

That same year, established YA prose author Jennifer L. Holm and her brother Matthew Holm released a comic targeted at grade-schoolers called Babymouse, through Random House. That only came after years of rejection from other publishers. “It was a hard sell,” Holm recalls. “There hadn’t been a pure comic for kids. There were some hybrids like Captain Underpants” — an illustrated kids’ novel series begun in 1997 that featured bits of comic-book art — “but not full comics.” When Babymouse finally found a home, comics for kids were so uncommon at mainstream publishers that Random House didn’t even know how, exactly, to print a full-color comic. After what Holm refers to as some “MacGyvering,” they figured it out, and Babymouse became a smash.

The engine of change spun faster and faster in the following few years. YALSA debuted a “Great Graphic Novels for Teens” list. Gene Luen Yang’s youth-friendly 2006 graphic novel American Born Chinese became the first comic-book finalist for the National Book Award. Longtime comics entrepreneur New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly set up a publishing company for early readers called Toon Books in 2008. All of this success, however, can be seen as something of a prelude to the arrival of the woman everyone in the comics and kids’-publishing industry mononymously refers to simply as “Raina.”

Perhaps the closest analogue for Telgemeier is Elvis Presley — a charismatic and visionary creator with a memorable name who became the face of a nascent movement and elevated it to unprecedented heights of popularity with deceptively simple pop art. She’d grown up in the San Francisco Bay Area, eschewing superhero material in favor of Sunday funnies like Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes and Lynn Johnston’s For Better or Worse in the ’80s and ’90s. A kid who liked to draw, she began emulating them at a young age. “I think comics were really appealing because I could do them myself,” she remembers. “It didn’t take many resources, just a pencil and paper. At the end of the day, I needed to sit down and process what had happened to me that day, and I would do it through comics. So, I was drawing journal comics from the time I was about 11.”

Telgemeier continued those journal comics all the way through the end of college, building up a hefty corpus of juvenilia before meeting Joey Cavaleri, one of her teachers and an editor at DC Comics. He got her a slot for a short comic in DC’s 2005 anthology Bizarro World, and her professional career began. It was a rocky start, largely consisting of personally selling self-xeroxed mini-comics at conventions, but at the San Diego Comic-Con, she caught the attention of Saylor, who saw in her a raw and untapped talent. They met again at a festival held by New York’s Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art soon after, and he asked her to come meet with him. He needed someone to work on a Graphix initiative to make graphic-novel adaptations of The Baby-Sitters Club, and asked her to take it on. Nervous, she accepted the task.

“She ended up being this perfect storm of talent and energy and content that just really worked,” Saylor says of Telgemeier’s Baby-Sitters Club work. Filled with deliciously thick lines and vivid facial expressions, the books raised her profile and the material flew off the shelves, but they were, at the end of the day, adaptations, not a pure expression of Telgemeier’s vision. That only came in 2010 with the release of her first masterwork, Smile.

It was an account of the author’s life from sixth grade through high school, with the running motif of her various tooth-related problems. As innocent as it was insightful, it was as good as any work in the Youth-Comics Explosion had been. Mainstream reviewers took notice: “Drawing in a deceptively simple style, Telgemeier has a knack for synthesizing the preadolescent experience in a visual medium,” wrote Elizabeth Bird in the New York Times; Kirkus called it “[i]Irresistible, funny and touching—a must read for all teenage girls, whether en-braced or not.”

Thanks to the deep market penetration of Scholastic’s book fairs, Smile became an insane hit, unlike anything that preceded it in the modern youth-comics market, going on to spend more than 200 weeks on the Times’ comics best-seller list. After it came 2012’s Drama, 2014’s Smile sequel Sisters, and last year’s Ghosts — all of them sensations. Though the quality of the books and Scholastic’s wise distribution efforts were key, so too was Telgemeier’s personality and willingness to tour. On her nationwide jaunts, she started to see the human impact of her work.

“I was seeing how many kids were coming to my events with these amazing dog-eared, falling-apart, taped-together copies of my books,” she says. Even when they couldn’t meet her in person, they showed their enthusiasm. “Kids were sending me drawings and they were quoting my scenes and there were YouTube videos re-creating my stories,” she says, sounding awestruck.

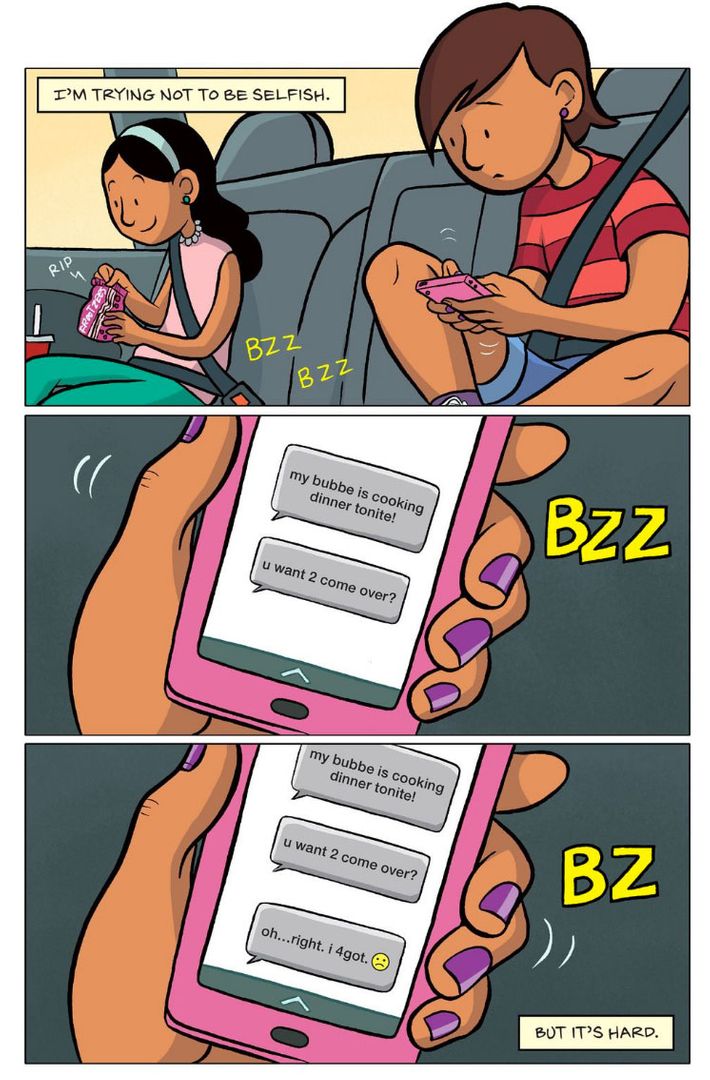

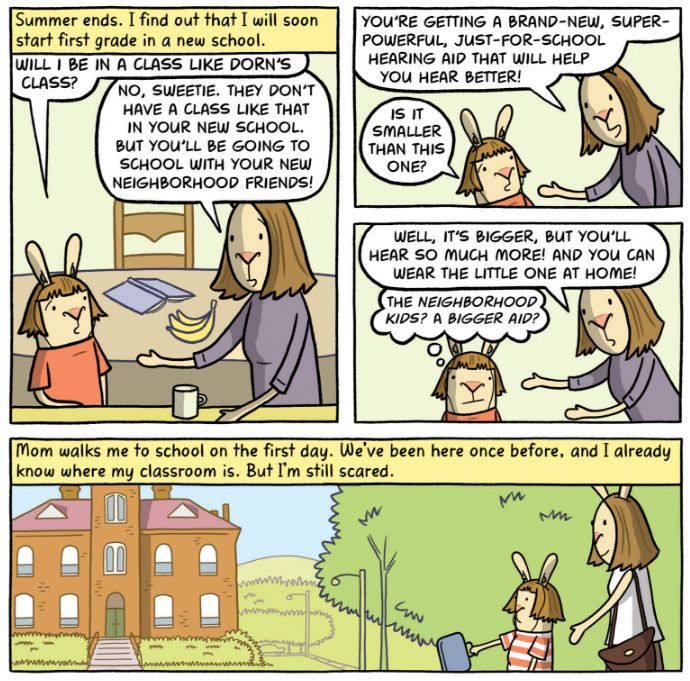

Telgemeier’s brand of slice-of-life comics for grade-schoolers opened the door for an array of creators with similar instincts, such as Cece Bell, whose hit 2014 graphic novel El Deafo depicts her childhood struggle with hearing loss; or Svetlana Chmakova, whose manga-influenced Awkward and Brave chronicle attraction and rivalry within diverse student communities.

But the Youth-Comics Explosion has also brought a cornucopia of other options for young people of various ages. Want an elegant account of queer teen romance (created by an actual teen, no less)? Try the works of Tillie Walden. Looking for sci-fi action with a strong female lead? Check out Scott Westerfeld and Alex Puvilland’s Spill Zone. Interested in team adventure with a fantasy twist? Grab BOOM!’s massively successful ongoing series Lumberjanes. Want some humor mixed with horror? Pick up Mariah Huehner and Aaron Alexovich’s Stitched, published by Papercutz. Interested in a solid take on a classic? IDW Publishing’s My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles titles are aces. The list goes on and on.

One of the most remarkable things about the Youth-Comics Explosion is how much it reaches out to young girls — a population long alienated by mainstream superhero comics. That’s due in no small part to another remarkable thing: A massive portion of the people creating these comics are women, something unheard of in the majority-male space of superhero-comics publishing.

“There tends to be an attitude at some of the major publishers that it’s impossible to find women to work on books, and that’s not true,” says Huehner, who also edits Charmz. “If you’re gonna tell stories for young women and girls, I think having a creator who has experienced that matters a lot.” Hibbs has set up a graphic-novel-of-the-month club for kids at his store, and has noticed that there’s about a 70/30 percentage breakdown of girls and boys among his kids’-comics buyership. Those kinds of numbers represent a drastic shift from the comic-shop buying demographics of even just a decade ago, and will change the future of the medium.

Indeed, for the first time in a long time, it seems like there is a long-term future for comics. No wonder Marvel and DC are trying to get in on the action: Those who think about what youths want in their sequential art have the opportunity to plan for holding on to comics readers who will still be alive 70-odd years from now. Holm has seen those generational effects already. “Now it’s funny if I go to an event, because some college girls will say they grew up reading Babymouse, and it’s like, God, I’m really old now,” she says with a laugh.

Perhaps Lumberjanes co-creator and BOOM! editor Shannon Watters best sums up the promise of this vibrant moment. “For kids, the media that they consume, but especially books — especially books — are extremely personal,” she says. “So when you’re making these books that just speak to them in this very profound way, it’s really, really special. It makes everything worth it when you have kids coming up to you and telling you that your books changed their lives.” And not only their lives, but the life of an entire medium. I’d better start asking my sister for more book recommendations.