“You know when you realize you’re getting stains on your shirt,” says Judd Apatow, “and it’s because you’re starting to sweat and there’s nothing you can do to stop it?” He shakes his head. “That’s all I could think about last night.” It’s a hot midsummer morning, and Apatow, leaning back in a chair at a conference room in the New York office, is wearing a (stain-free) Pearl Jam T-shirt and talking about the stand-up gig he played the evening before. “I kept leaning forward in a weird way so my shirt wouldn’t be up against my chest.” He gives a resigned shrug. “Every set is different.”

The mechanics of stand-up have lately been consuming the celebrated writer-director. After remaking the template of Hollywood comedy, via his own movies (Knocked Up, The 40-Year-Old Virgin) and the films and TV series he’s co-produced (Girls, the sleeper hit rom-com The Big Sick), into its current, more naturalistic shape, Apatow has, in recent years, gone back to his performing roots. In addition to spending a chunk of the summer touring in clubs, the 49-year-old has a Netflix special due later this year, taken from his performance at July’s Just for Laughs comedy festival in Montreal. (He also opened for Dave Chappelle during the latter’s Radio City Music Hall residency.) And while the renewed focus on stand-up means another cinematic auteur effort from Apatow probably isn’t coming anytime soon, it also means that one of the most influential comedy minds of the past decade is working through his obsessions and anxieties publicly, in real time. “The stuff I want to talk about,” he says, “is the stuff I’d be talking about even if I were just sitting around at home.”

Why exactly are you spending the summer slogging through stand-up gigs again? I mean this as respectfully as possible: Is going back to the work you were doing as a 21-year-old your version of a mid-life crisis?

I don’t really know the answer. Maybe I just have low self-esteem and need to hear people laughing at my jokes. Or maybe I’m overcompensating for the part of me that never wants to leave the house. When I go back and think about what I was doing as a young comedian, I know I had a great passion for stand-up, but I was never sure if I was the one who should be doing it. I was a big enough fan of the work to know how much better other people were than I was. Just to pick one person: The first time I saw Rob Schneider do stand-up back in the late ’80s, it was really intimidating. I thought I was good, but I wasn’t anywhere near his level.

So in this moment, what’s the answer? Are you back onstage because of low self-esteem or a desire to get out of the house?

In simple terms it’s this: Stand-up is what I love more than anything else. There’s something fantastic about thinking of a joke in the shower and then doing it that night at the comedy club. With a movie, it’s years of work, getting very little feedback, and then you find out in two hours at a screening one night if all that work was worth it. The feeling I get from stand-up, of being more connected to audiences, is really good. Stand-up makes my other work better, too. When I’m giving notes to Pete Holmes or Paul Rust, it’s now coming from a place of being in touch with what people out in the world are actually laughing about. It’s easy to lose touch with reality when you’re just sitting in your house.

Feverishly scanning Twitter.

Yeah — politics has ruined Twitter. People used to talk about silly things on there, about comedy, about culture. Now everyone’s just mad all the time.

The criticism of Twitter went from “Who cares about what someone else is eating for breakfast?” to “Does it facilitate hate crimes?”

The sense of fun is gone. It really is.

But you’re not shy about being pretty aggressive on there. Are you ever concerned that by being so active on Twitter and speaking out so strongly about politics, you’re just adding to the feeling that we’re all yelling at each other all the time?

No, because comedians are supposed to point out madness and hypocrisy. What I’m doing is pretty straightforward: I think we have an incompetent, corrupt president, so I point that out. And it’s also the comedian’s job to give people some levity — we’re all so stressed out now from not being able to trust the person in charge of the country. Every comedian has to decide the tone of the joke that they’re comfortable with, but what are we all going to do? Not talk about what’s going on? Should we have not made jokes about Monica Lewinsky or George W. Bush invading Iraq? This is how we have our national discussion.

It wasn’t that long ago when all mainstream audiences expected from comedians was to wear a blazer and tell inoffensive one-liners. Why has there been this shift in comedy toward moralizing and self-confession?

It’s because people are hungrier for honesty now, which is something they’re not getting from other places. Comedians have no motivation to lie and almost every other public figure we encounter nowadays does. Politicians are lying to you all day long; comedians are telling you what they really feel. I think it also has to do with the enormous media need for content. People uploading their personal experience, in whatever format, has become modern entertainment. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I’m as interested in a guy telling me about his daily difficulties as I am in a well-crafted movie. Chris Gethard has a podcast where he just talks to whoever calls in. Some of those episodes are perfect, and they’re just honest conversations. But a politician can’t do that. How many Republican politicians would tell you, when no one else is listening, that they’re against a woman’s right to choose? I assume the truth would be a lot fewer than publicly admit it.

Wait, why would you think Republican politicians are lying about their abortion beliefs? That strikes me as an issue where their private and public beliefs probably do line up.

I don’t think it’s mathematically possible that you’d get 50 people to agree on a single issue, whether or not that issue is abortion and whether or not those people are senators. There are certain issues that each party decides are important, and on these issues every single elected member of the party agrees with the party line? These people are just saying what they think they have to say in order to keep their jobs.

There was a New York Times piece that Ross Douthat wrote after the Girls finale that argued the show was a critique of liberalism, insofar as it had all these young liberal men and women and all their liberalism got them were unstable messy lives. And it’s no secret that your movies tend to resolve with characters finding happiness in pretty traditional relationships. At heart, are you a traditionalist?

I don’t know about traditionalist, but what I want is for characters to do better. I want people to get it. There’s only so many stories, right? Either someone gets it and learns a lesson or they don’t. The 40-Year-Old Virgin: either he has sex and it’s bad, or he has sex and it’s good, or right before he has sex he gets hit by a truck and it’s sad that he never got to have sex. I know who I am as a storyteller: I want to feel hope about people’s abilities to incrementally learn. This is related to the reason why you don’t see movies and television about Republican and conservative ideas — because Republicans are trying to present themselves as correct, as clean, as Mike Pence–y. Unlike them, I want people who actually evolve. Does it make me a traditionalist if the way they evolve is toward a healthy relationship? Maybe.

Could you write a movie about someone like Mike Pence?

When you see Mike Pence, you think there’s a lot going on inside that guy. At least I do. But the problem is that Mike Pence will not tell you that. Lena [Dunham] will. There’s an openness and an honesty to what she does. She’s saying, I have these values, but I’m also a human being, and I make mistakes, and sometimes I’m crazy and selfish and other times I’m loving and supportive. And that’s why there’s no incredible, hysterically funny show about conservatives, because they’re too concerned about trying to present themselves as correct. They’re all going, I’m not neurotic. I’m not a disaster in any way. They don’t admit how lost they are. There’s something dishonest to me about that; it’s living a lie. So for someone to say that Girls is a critique of liberalism because the characters’ lives might be disasters? No, those characters’ lives are disasters because they’re human.

What do I know, but wouldn’t the conservative counterargument be that the traditional values and institutions that they embrace and that someone like Hannah Horvath rejects actually do help them feel less lost?

What you’re talking about is an illusion of stability. It’s a household from the 1950s where the family is in a living hell because the dad’s a secret alcoholic. We’re either going to be honest about what’s going on in our lives or we’re not. To me, what’s interesting is people telling the truth about the fact that they’re a mess. It doesn’t matter who they are. Hillary Clinton’s a mess. Trump is obviously a mess. But I do think Hillary Clinton could probably talk to you about what she struggles with and the mistakes she makes. Can you imagine Donald Trump doing that? Can you imagine him going to a therapist? He might do a better job if he did.

What’s he need to work through?

Here’s a guy whose parents sent him away to boarding school. They didn’t send his siblings away. They sent him away because he was unmanageable. What did that feel like? Was that an abandonment? Did it make him feel the need to prove himself? And is he incapable of ever proving himself enough to get over that injury? Maybe if he went to therapy he wouldn’t feel the need to be right all the time. I actually wish Donald Trump made a series like Girls but about himself. I’d like to see him have fun with his pain and his mistakes and his triumphs. But that’ll never happen.

You never know. Maybe he just needs to find the right therapist.

I hope so. I had a therapist once who told me that I should meditate, because in silence and nothingness is where the good stuff is. Not in my experience. I sit and meditate and … it’s like, I’m always trying to “love the mystery.” So far in my life I don’t love the mystery at all. I don’t want it to be a mystery. I want answers.

So you gave up meditating?

No, I still try.

There’s another comedic shift that’s happened that people have held you up as being at least partly responsible for. It’s so rare that we see broad joke-joke-joke comedies like Airplane! or The Naked Gun or Spaceballs anymore. Is that just because your more naturalistic style is what’s in vogue? Or do you think audiences don’t want that kind of over-the-top, totally unrealistic comedy anymore?

When you make the list of the best movies of all time, you’re always going to put Airplane! on it. And if movies like that aren’t being made right now, it’s because people aren’t smart enough and funny enough to make them. I don’t think it’s a result of studios or audiences rejecting anything or trying to copy anything else. If someone made a movie as funny as Airplane! right now it would make a billion dollars. Occasionally people try; most of the time they fail. When you do a big, broad comedy and it fails, it’s an easy target for criticism. I also don’t think critics have a great respect for the effort it takes to make people piss their pants laughing. They think it’s more honorable to show someone in torment, but being able to do that doesn’t make you more of an artist than being able to make The Naked Gun. It’s not hard to make people cry. Kill a dog.

Simple.

I also think that something has happened with studio comedies that no one ever talks about.

Which is what?

Which is that after the last writers’ strike, it felt like the studios decided not to develop movies. They used to buy a lot of scripts, and they had big teams of people giving notes, and they worked for years with people in collaboration on those scripts. I feel like the studios don’t buy as many scripts now. It used to be you’d open up Variety, and you’d see a movie studio had just bought a big high-concept comedy. Now it seems like they’d rather things come in packaged: a script, a cast, a director. As a result, a lot of great comedy writers are going to television instead of sitting at home and trying to write a script for a film, write the way I was.

You work with young writers all the time. What’s the note you give most often?

I know what I used to say to Seth Rogen: “Less jizz, more heart.”

Was that a note you gave on Bridesmaids?

The truth is that my notes are always the same. I push people to dig deep. If we can get to a very honest place, the comedy part won’t be difficult. The jokes are what’s easy. If you talk to Amy Schumer about her life and her relationships and her relationship with her sister and her father, there’s an amazing story there. For a long time while we were working on what became Trainwreck, we only talked about the movie as if it were a drama. Once all of the emotions were credible and organic, it wasn’t hard for her to then make it hilarious. Nothing I tell people is very complicated.

It’s interesting that your career has had a flip-flop in regard to feminism. It used to be that you were criticized for having shrill female characters and for seeming to only be interested in immature men hanging around with other immature men. Then you worked with Amy and Lena and on Bridesmaids and you were seen as something like Hollywood’s highest-profile male champion of women comedians. So I have two questions: Did you think there was anything to the criticism that your work was misogynist? And did getting that criticism make you think any differently about what you wanted to do moving forward?

No. I never felt any of those criticisms were accurate. I produced Roseanne’s stand-up special in 1992. Freaks and Geeks was about Lindsay Weir. So, I never felt like the idea that I wasn’t interested in women or was portraying them negatively warranted much reflection. The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up are satires of immaturity, and in a lot of ways, the projects I worked on that people suddenly thought were about championing women were just the female version of that — of showing someone figuring out how to grow up. So no, none of my work has been a reaction to anything. People talk about the Bechdel test. Leslie [Mann] has been giving me that test for decades.

Do you think of yourself as feminist?

I don’t, at least not in those terms. I just try to do what’s right whenever I see the opportunity. I’m sure I make mistakes. But I’m not working with Lena because I want women to do better; I’m working with Lena because she’s so inspiring. With Bridesmaids, I never thought, It’d be great if there was a movie that starred a lot of women and maybe that will help open some doors. It’s great if that ends up happening, but that sort of thinking is never the starting point. Same thing with The Big Sick. I’m not thinking about representing minorities. I’m not thinking about society. I’m thinking, No one else’s ever made a movie about someone like this. That means it’s not going to be hacky. It’ll be new. Now let’s make it great.

Is there a part of you that wishes things had played out differently with Katherine Heigl?

It’s like this: When you make a movie, you become a family. I felt like we all did a great job — and she did an incredible job — on Knocked Up. She couldn’t have been more fun to work with. Then to learn that she had reservations was difficult. But that’s what happened. There’s nothing you can do about it. We’ve all had opinions about the work we’ve done, but what’s a drag is that the negative ones separate people. Because what you really want to do is make something and then for the rest of your life be able to call the people you made it with and say, “Wasn’t that fun? Wasn’t that great when we did that thing?” Now we can’t do that.

Neither one of you ever tried to bury the hatchet?

No. I’ve heard that she felt bad about what she said and I don’t want her to ever feel bad. I’d like her to love the movie as much as I do.

Your act has a lot of material about your daughters.

I don’t want to talk much about my jokes. That’d be giving my act away.

I can be general. Do you talk with your kids about what kind of jokes you’re allowed to make about them? I could imagine some of it being pretty mortifying for a teenager.

I’m very careful with what I say. Most of the jokes are more about me than them. Basically what I’m saying about parenting is that in a faster-moving world, a world that encourages less quiet and more vanity, there are new challenges to raising kids. Probably the kids are fine; it’s the parents who are having the nervous breakdowns. Every generation deals with this stuff. When I was a kid I used to watch TV from 3:30 in the afternoon till 1:30 at night. I watched The Merv Griffin Show, Dinah Shore, Mike Douglas, Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, and then Letterman and The Tonight Show. My parents were terrified, and because I wouldn’t stop watching TV they bought me a KX80 motorcycle, the most dangerous machine, just to try and get me to go outside. That’s how concerned they were. And the way they felt about TV is how I feel about social media: Is this okay for my kids? It probably is, but my terror is funny.

Is having a daughter in college also terrifying?

I talk about this in my stand-up a little. You know kids are getting obliterated with alcohol, so you try to make concessions based on what you know the realities of college drinking are. You start out saying, “No, don’t drink.” Then that turns into, “Okay, two glasses of wine. Can you please just do two glasses of wine?” How do you teach your kid to be satisfied with a gentle buzz? That’s the challenge.

I sort of touched on this earlier: All your films feature a protagonist that could reasonably be called a man-child. Why is that archetype so interesting to you?

I never thought I had anything to do with the man-child archetype the way people talked about it — as these guys who were freaking out about marriage or responsibility. The male characters in my movies are just my version of Bill Murray in Stripes. I love that movie so much: It’s Bill Murray and Harold Ramis and John Candy just hanging out. Movies like that are in my cells; those are the movies I want to see and I want to make. I want more Stripes. I want more Meatballs. I want more Ghostbusters. I want more Animal House. Those movies were also about growing up, by the way: Bill Murray eventually led the troops in Stripes.

So you felt you were working in a tradition rather than examining something new about the way modern men behave?

What I do is a variation of something that comes from people like Ivan Reitman and John Landis and Harold Ramis. And a person that a lot of people don’t talk about in this regard, who was a giant inspiration, is Barry Levinson. Diner is ground zero for most modern comedy. Before there was Quentin Tarantino or what I do or Jerry Seinfeld or Kevin Smith, there was Diner. I can’t find the movie before Diner where people talk like [that] and where we saw friendships like that. It’s so funny and well-drawn and honest. Paul Reiser in Diner — I loved that character.

But aside from trying to emulate the people who inspired you, why are you so drawn to male characters that want to spend their time joking around and getting high with other dudes?

I like writing about that stuff because that’s what young life is about. When you’re in your early 20s or in high school or college, you don’t hang out with women. You hang out with a bunch of dudes, and you try to beg women to talk to you. But most of your life is around men and then slowly you get female friends or you get a relationship or you get married. But the beginning of your adult life, which is what I’ve written about in various ways, is when you’re stuck hanging around with your own sex.

To go back to stand-up for a second: You’ve said that one of the reasons you weren’t a better stand-up early on is that you didn’t have a strong or distinct persona. Have you fixed that problem?

Ask me after the Netflix special airs. Part of the issue when I was younger is that nothing much had happened to me. Now, just by being older, I have more to say. I’ve lived a little. I mean, the other thing is that it took me ten years to figure out how to process my life experiences and turn them into stories. That was all thanks to Garry Shandling.

What’d he teach you?

I met Garry in between It’s Garry Shandling’s Show and The Larry Sanders Show, and in between those shows is when he decided he wanted to do something that was truthful, a deep soul-dive into what mattered to him. He was gracious enough to just allow me to be around, watching him write, make cuts, criticize his own work. All the information I gathered by hanging around him went into my brain somewhere, waiting for me to apply it. The only reason I ever directed was because I was writing for The Larry Sanders Show, and one day Garry walked into my office and said, “You’re directing the next one.” It was one of the kindest, most intuitive gestures anyone’s made towards me. I would never have asked to do it. I would never have thought, I should be giving notes to Rip Torn. When I was a kid, I just wanted to be a stand-up. Then I got into writing. I wasn’t studying cinema. I might never have a directed a thing if it wasn’t for Garry. I owe him so much.

The autobiographical impulse that you took from Garry is so central to your work. But the success you’ve had with that has maybe also contributed to this glut we have of supposedly comedic sitcoms and movies and podcasts where it seems like the point is to be emotionally honest first and funny second. Is it possible that all this emphasis on personal truth has made comedy less actually funny?

It’s possible that people sometimes don’t realize that no one else cares if something is true. The truth is only the beginning of the artistic expression. Kumail [Nanjiani] and Emily [V. Gordon] and [director] Michael Showalter and I talked about this when we were working on The Big Sick. We would always start with the truth of the situation — or as close as we could get to it — and then there would also always be a moment where we’d say, “Now let’s make it a great movie.” In order for real-life material to function as a great movie, you have to adjust it.

How’d that work with The Big Sick?

In real life Emily’s parents are very nice — probably too nice to be interesting enough for a movie. Their actual reactions to the situation were not going to drive the movie properly. So we said, “What if these people had marital problems?” And that created new levels of dynamics that helped that story. That’s what you have to do. Garry, for example, always said the difference between him and Larry Sanders is that Larry Sanders could never have written The Larry Sanders Show. So even though the show was about self-exploration, there were enormous parts of Garry that weren’t in it. The spiritual-seeker aspect of Garry wasn’t there, for example.

Have you read any good self-help books lately?

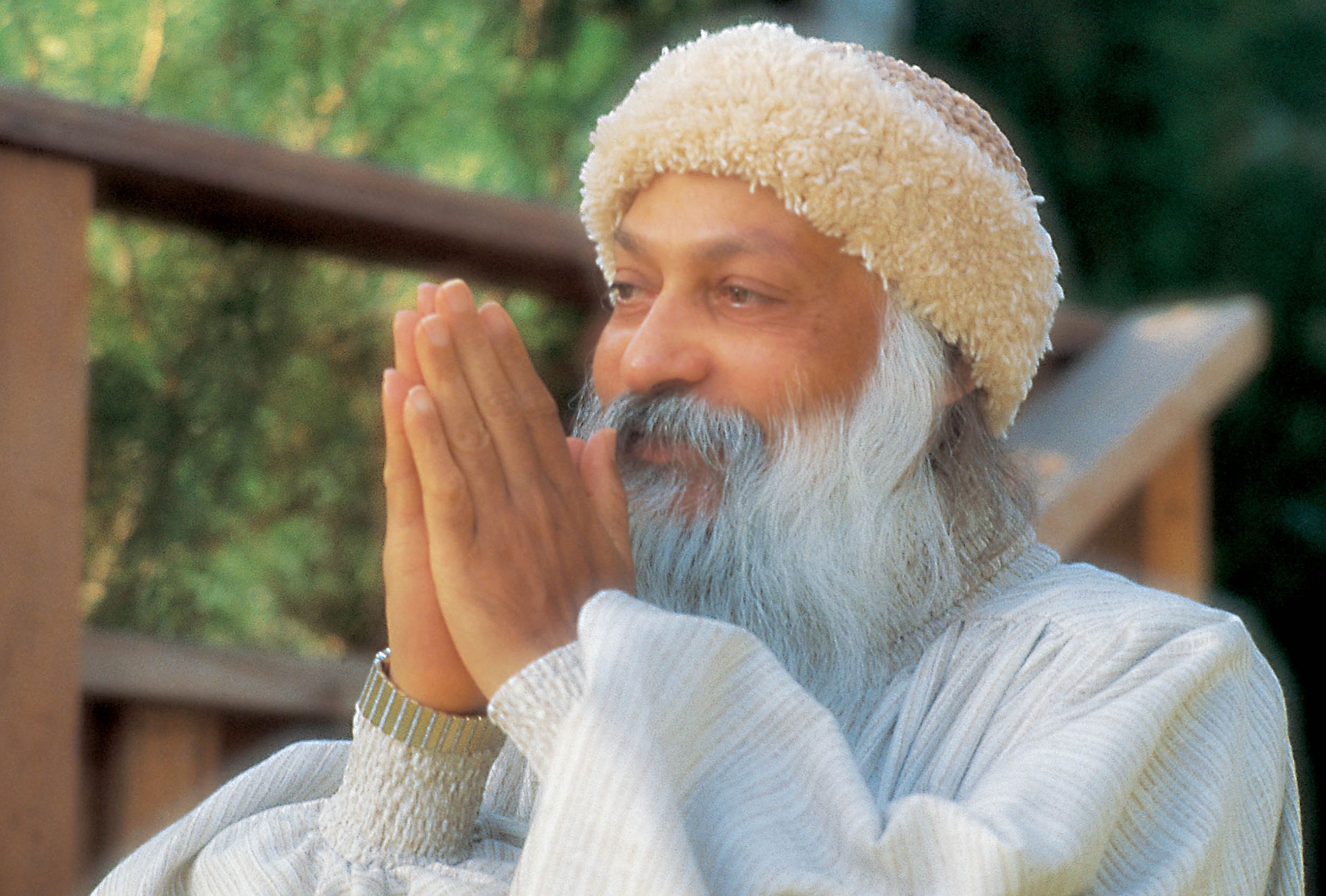

It’s funny, because Leslie and I were watching this Bill Kurtis show, I think it’s called Through the Decades or something. It’s just documentaries about old news stories. They were showing this one about a guru who came to America in the ’70s or ’80s, and he had all of these followers in Oregon and created this city. It led to some story about how one of the guru’s followers supposedly poisoned hundreds of people with salmonella. The whole community just melted down. It was crazy. The guru eventually changed his name to Osho. So we were watching this show about this crazy situation Osho was involved in, and I turned to Leslie and said, “I’ve got a couple of books by him.” Then Leslie and I had this discussion about who are all these self-help people that I’m listening to? Who writes these things? I just blindly trust that these people are not evil. But I do get a lot out of self-help books. There’s almost always something valuable in them. Sometimes I think that I should just write down the four best things I learned from each one I read and make a master notebook of everything I’ve learned.

The Judd Apatow self-help compendium is a million-dollar idea.

Maybe I’ll do it some day. Right now I’ve been reading these Brené Brown books. They’re all about how hard we work to avoid feeling vulnerable and how afraid of shame we are. She’s all about the importance of just admitting what you’re feeling and not trying to hide. That had a big effect on me. Actually, maybe that’s why I do stand-up, because I have an instinct to want to hide and stand-up forces me to like myself enough to think I’m worth listening to.

Aside from stand-up, how does self-help affect your work?

The books always have a zillion examples of problems that people have and the wrong ways to deal with them. You’ll get an example like, “Here’s Bill, and he doesn’t get along with his wife, and this is the wrong thing that he keeps doing, and this is why she gets mad.” As a writer, I like to know what the wrong instinct is — that’s where the comedy is. And those books are just full of examples of people acting on the wrong instincts. They’re an amazing resource for me.

What you were saying a minute ago about Osho, and the idea that people who have maybe done horrible things might also have done admirable things, made me think of someone who I think used to be a hero of yours: Bill Cosby. Does the seeming fact that he’s a monster mean he’s erased from comedy history for you?

Well, his comedy doesn’t mean the same thing as it used to. The filter’s different now. Suddenly you notice certain ideas that you didn’t realize were always there. On his albums he’s always the put-upon dad who feels mistreated and doesn’t want there to be rules and wants to get his own way. And some of his stand-up is really hostile. He has bits about fighting with his wife. He talks about getting physical. There’s a lot of bits about feeling tricked into marriage, not having freedom.

His bit about Spanish Fly went from kind of gross to extremely disturbing.

Yeah, where he talks about the dream of Spanish Fly. Like, “Wouldn’t it be great if it works?” That doesn’t mean I couldn’t get in a certain headspace and listen to the “Chicken Heart” [routine] and laugh. I probably can. But it’s very, very difficult, and I don’t want to. It’s tragic. It’s tragic that somebody that inspired so many people was so sick. It soils everything he’s done. But what he did for comedy happened. He did knock down all those walls. He did inspire people. But you could also realize it’s 2017 and pick a new person to be inspired by.

What’s a criticism you’ve read of your work that was useful? Has there been one?

No, because I already think about all of the problems with my movies. I used to read every piece of criticism about my stuff, but it became too hard to know what to listen to and what not to listen to. I think I have a good understanding of how people experience movies, and sometimes the truth is that I’m in a real please-the-crowd mode and sometimes I’m not.

I would say you’re mostly not in please-the-crowd mode in the cutting room.

I’ll tell you something: When we were making Funny People, I was sitting in the editing bay reading all of these interviews with John Cassavetes. He was always talking about how he didn’t want you to just love the movie on the day you saw it, he wanted it to be stuck in your craw ten years from now. His movies almost make a point of leaving you not feeling good. Sometimes I want to do the same thing, and it’s very hard to do anything like that in the modern movie system. Like I said before, I like to watch people evolve and learn things, but I also want to talk about how hard it is to learn things.

What’s an example?

On Funny People, I was aware that I wasn’t taking the story in a direction that people were expecting, and that my point was not a point that people get very excited about, which is that it’s very hard to learn some of the lessons we need to learn in life — even if you’ve just had a near-death experience. I’d been inspired by some articles about business executives talking about having cancer, and instead of saying how it changed them as a human being, they talked about how it changed their approach to business. They didn’t seem to have learned the right things from the experience. There was no sense of appreciating life more. And also my mom passed away from ovarian cancer, and I’d watched her go on a terrible roller-coaster ride of thinking she was going to get better and then thinking there was no hope, and then suddenly there was a new treatment and she thought she would get better and then she’d get worse again. I saw how when she was sure she was going to die she seemed much more at peace, and a lot of her daily concerns disappeared. But I have to assume that if she’d gotten a new treatment and had another year of life, she would’ve gone back to being neurotic about the same stuff she was always neurotic about. It’s hard to hold on to any peace you find. That’s what I was trying to talk about with Funny People.

Yeah, it doesn’t quite register as a triumphant ending to Funny People when you see that Adam Sandler’s character has only taken a baby step toward self-awareness.

The movie ends with him writing a dirty joke for Seth’s character. That’s the big change. At the beginning of the movie he wouldn’t have written a joke for a young comic; he would have gotten a joke from a young comic. So maybe that was a first step for him. I hope he can build on that. I don’t know if he will. There’s a good chance he won’t. But that’s as far as he got in this very long movie. With Funny People, I tried to make it as funny as I could — where appropriate — but still have difficult ideas.

Going back to Freaks and Geeks, you showed that you have a knack for talent-spotting. Who’s someone you thought was great but never got a vehicle to show off just how great they were?

I actually think most actors and actresses have untapped potential. One of the things that blew my mind on The Larry Sanders Show is how all of these guest actors and actresses would come on and you’d realize they were masterful. They’d just never gotten the opportunity to showcase that mastery to its full effect. It’s so rare that someone hands an actor the script to Kramer vs. Kramer. Everyone’s doing the best they can, trying to make a living, but a lot of people are way more talented than you ever can imagine.

Like who?

It’s not the best example, because he did have some opportunities to showcase his greatness, but when John Ritter was on The Larry Sanders Show we were all completely rocked watching him work. People’s jaws dropped at how talented he was. I remember loving him in Sling Blade. He had another 30 Sling Blade–caliber parts in him. He just never got the chance to prove it.

On the subject of the work actors can and can’t get: Every once in a while you’ll see someone like Tim Allen say that conservatives are risking their Hollywood careers if they talk about their political beliefs. You’re an outspoken liberal. Would you hire an outspoken conservative? It’s easy to imagine a role for Kelsey Grammer or James Woods in one of your movies.

It’s hard to know. What is a conservative these days? If somebody believes in lower taxes and is anti-abortion, does anybody care that they’re a conservative? I don’t think so. I think if you’re crazy, regardless of what party you’re with, people don’t want to be around you. Does anyone care that Kelsey Grammer is a Republican? No, he’s a genius. He’s one of the greatest comedic actors of all time. I’d work with him in a second. I respect people who have different points of view. What I don’t like are cruel people. People who are consistently vicious are troubling.

It’s been five years since This Is 40. What’s your next movie going to be about?

I don’t have a script I’m working on.

Not even a germ of an idea?

I have nothing on the horizon.

And you feel okay about that? Or is that anxiety-inducing?

It’s both. There’s a part of me that thinks if I went 15 years between movies, it doesn’t matter. Who’s it for? Is it for me? Is it for the audience? Is it to just stay in the game? I’m trying to just relax and see if something comes to me. Your work is always going to be terrible if you make a movie just because it’s been a while. And I have such a good time helping other people with their ideas, that sometimes I think it doesn’t matter if I write or direct, as long as I’m involved in projects I like. I have plenty to keep me engaged.

I read somewhere that you and Owen Wilson once took a cross-country road trip in order to work on a screenplay. I’ve never heard you talk about that. Were you guys just doing a Kerouac?

That was very early in Owen’s career, right after Bottle Rocket. I hadn’t even directed anything yet. Here’s what the script was: It was about a guy who gets in a drunk-driving accident and as part of his sentence is forced to go to 20 Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. Owen was going to play that guy, and in the script he meets an older gentleman played by Rip Torn, who convinces Owen that he is an alcoholic. Owen thinks he’s just a guy who one time got in a drunk-driving accident.

Sounds funny.

Well, I was never able to get anyone to make it. The reason Owen and I went on the road was to go to AA meetings in different cities and see what they were like. The script I wrote, I like a lot. The only time it was ever performed was in my living room. Me, Owen, and Rip Torn. Having Rip Torn sitting in my living room reading this thing was the best experience of my life. I was devastated that I couldn’t get a green light for it. That was actually an interesting experiment for me, because I used to think that in order to make a movie you had to spend years and years and years on it. That’s what I did in that case, and then when I couldn’t get it made I thought, I just wasted almost a half-decade of my life. From then on I started developing more projects simultaneously. I got myself involved in more things.

Weren’t you writing a play recently? What happened with that?

I couldn’t crack it. I sat around for a year and I didn’t write one word.

What was the concept?

I had several different ideas for plays. I’d rather not say them in case I actually do one of them one day. I did a lot of research; I did not write one letter. I really was daunted. I don’t know if I got afraid of failing or if I just didn’t have whatever it is you need to write a play, but I accomplished nothing. Sometimes I think it’s good I didn’t get anywhere, because I would have been much less helpful on The Big Sick if I was deep into writing a play. So it all worked out. I might try again with a play some day.

But really, you don’t even have the tiniest inkling of an idea for a new movie?

I don’t! I might just take it easy and make the next year more of a reading year for me. It’s also a weird moment right now, because you feel like entertainment is a digital black hole. There’s endless need for content and people are burning through things so fast. It makes you wonder how you can have any sort of impact. And what does impact even look like anymore? And should you even be thinking about impact? And how do you change your approach if you are thinking about these things?

So what’s the answer?

To which one?

Any of them.

I’m not sure. That’s why I read self-help.

This conversation has been edited and condensed from two interviews.

Maude, 19, and Iris, 14. In Knocked Up and This Is 40, they played the daughters of Mann’s and Paul Rudd’s characters. Maude has also appeared on Girls, while Iris has a recurring part in Love.

Maude, 19, and Iris, 14. In Knocked Up and This Is 40, they played the daughters of Mann’s and Paul Rudd’s characters. Maude has also appeared on Girls, while Iris has a recurring part in Love.

Reitman directed Meatballs, Stripes, and Ghostbusters. Landis directed Animal House, The Blues Brothers, and Coming to America. Levinson directed Good Morning, Vietnam; Rain Man; and Diner, a 1982 hangout comedy about 20-something male friends the night before a wedding.

Reitman directed Meatballs, Stripes, and Ghostbusters. Landis directed Animal House, The Blues Brothers, and Coming to America. Levinson directed Good Morning, Vietnam; Rain Man; and Diner, a 1982 hangout comedy about 20-something male friends the night before a wedding.

As a teenager in the ’80s, Apatow interviewed the Johnny Carson guest host, then eventually scored a writing gig on Shandling’s influential The Larry Sanders Show. In 2016, Shandling died from a blood clot in his lungs. In an episode of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, Seinfeld broke down as Apatow recalled Shandling’s perfect timing and deep empathy. “There’s something about him that encompasses the human struggle,” said Apatow. “He was trying so hard to be happy, and to find peace, and to let go of his ego.” Apatow is currently working on a Shandling documentary.

From 1992 to 1998, HBO’s meta-comedy about a late-night host starred Garry Shandling, Jeffrey Tambor, Rip Torn, Jeremy Piven, Janeane Garofalo, and a litany of guest stars playing themselves. Shandling and Peter Tolan reigned in the writers room, along with Maya Forbes (Infinitely Polar Bear), Paul Simms (Atlanta), Jon Vitti (The Simpsons), and Apatow.

The director of The Big Sick, Showalter co-wrote and starred in the 2001 camp comedy spoof Wet Hot American Summer and its subsequent Netflix sequels.

As a teenager in the ’80s, Apatow interviewed the Johnny Carson guest host, then eventually scored a writing gig on Shandling’s influential The Larry Sanders Show. In 2016, Shandling died from a blood clot in his lungs. In an episode of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, Seinfeld broke down as Apatow recalled Shandling’s perfect timing and deep empathy. “There’s something about him that encompasses the human struggle,” said Apatow. “He was trying so hard to be happy, and to find peace, and to let go of his ego.” Apatow is currently working on a Shandling documentary.

From 1992 to 1998, HBO’s meta-comedy about a late-night host starred Garry Shandling, Jeffrey Tambor, Rip Torn, Jeremy Piven, Janeane Garofalo, and a litany of guest stars playing themselves. Shandling and Peter Tolan reigned in the writers room, along with Maya Forbes (Infinitely Polar Bear), Paul Simms (Atlanta), Jon Vitti (The Simpsons), and Apatow.

The director of The Big Sick, Showalter co-wrote and starred in the 2001 camp comedy spoof Wet Hot American Summer and its subsequent Netflix sequels.

Silicon Valley comedian Kumail Nanjiani and his wife Emily V. Gordon wrote the acclaimed 2017 comedy, which is based on their own relationship: A Pakistani-American comic ignores his parents’ candidates for arranged marriage, falls in love with an American who develops an autoinflammatory disease and must be placed into a medically induced coma.

A longtime anchor and TV reporter, Kurtis is currently the scorekeeper on NPR’s “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” and the host of Through the Decades, a look back at television history on the Decades channel.

Silicon Valley comedian Kumail Nanjiani and his wife Emily V. Gordon wrote the acclaimed 2017 comedy, which is based on their own relationship: A Pakistani-American comic ignores his parents’ candidates for arranged marriage, falls in love with an American who develops an autoinflammatory disease and must be placed into a medically induced coma.

A longtime anchor and TV reporter, Kurtis is currently the scorekeeper on NPR’s “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” and the host of Through the Decades, a look back at television history on the Decades channel.

Also known as Rajneesh, the Indian guru moved to rural Wasco County, Oregon, in 1981 to preach his philosophy of personal fulfilment and rejection of organized religion to thousands of American followers dressed in orange and pink. The Rajneeshees clashed with state and federal government after they took over the town of Antelope and renamed it after their leader. In 1984, the Rajneeshees contaminated salad bars in Wasco County to affect elections, which resulted in 751 salmonella-infected victims, the largest bioterror attack ever on American soil. (There was also an aborted plan to assassinate a United States Attorney.) Though he was not connected to the attack, Osho was deported the following year after pleading guilty to violating immigration law.

The 51-year-old author of best-selling self-help books like The Gifts of Imperfection — “It’s our fear of the dark that casts our joy into the shadows” — and Rising Strong — “Just because someone isn’t willing or able to love us, it doesn’t mean that we are unlovable.”

From Cosby’s 1969 album It’s True! It’s True!: “You know anything about Spanish Fly? No, tell me about it. Well, there’s this girl — Crazy Mary — you put some in her drink, man … Spanish Fly is groovy. Yeah boy. From then on, man, any time you see a girl: Wish you had some Spanish Fly, boy. Go to a party, see five girls standing alone — boy, if I had a whole jug of Spanish Fly I’d light that corner up over there.”

The 2009 comedy-drama stars Adam Sandler as a famous comedian who receives a terminal diagnosis, returns to stand-up, and tries to salvage his relationships.

Known for his acting roles in Rosemary’s Baby and The Dirty Dozen, Cassavetes also directed independent films that rejected studio money and influence in favor of emotional honesty. “I don’t care if it’s going to be a success,” he said in 1978, promoting his Opening Night. “I want those suckers to come in there and to see this movie, because they’ll see what they always wanted to be.”

Ritter, who died in 2003, played the male lead in ’70s TV comedy Three’s Company, the voice of Clifford the Big Red Dog, and a gay dollar-store manager in the Billy Bob Thornton drama Sling Blade. In his appearance in season two of The Larry Sanders Show, Ritter gets in a fistfight with critic Gene Siskel on the day when an Entertainment Weekly reporter comes to profile the show.

Also known as Rajneesh, the Indian guru moved to rural Wasco County, Oregon, in 1981 to preach his philosophy of personal fulfilment and rejection of organized religion to thousands of American followers dressed in orange and pink. The Rajneeshees clashed with state and federal government after they took over the town of Antelope and renamed it after their leader. In 1984, the Rajneeshees contaminated salad bars in Wasco County to affect elections, which resulted in 751 salmonella-infected victims, the largest bioterror attack ever on American soil. (There was also an aborted plan to assassinate a United States Attorney.) Though he was not connected to the attack, Osho was deported the following year after pleading guilty to violating immigration law.

The 51-year-old author of best-selling self-help books like The Gifts of Imperfection — “It’s our fear of the dark that casts our joy into the shadows” — and Rising Strong — “Just because someone isn’t willing or able to love us, it doesn’t mean that we are unlovable.”

From Cosby’s 1969 album It’s True! It’s True!: “You know anything about Spanish Fly? No, tell me about it. Well, there’s this girl — Crazy Mary — you put some in her drink, man … Spanish Fly is groovy. Yeah boy. From then on, man, any time you see a girl: Wish you had some Spanish Fly, boy. Go to a party, see five girls standing alone — boy, if I had a whole jug of Spanish Fly I’d light that corner up over there.”

The 2009 comedy-drama stars Adam Sandler as a famous comedian who receives a terminal diagnosis, returns to stand-up, and tries to salvage his relationships.

Known for his acting roles in Rosemary’s Baby and The Dirty Dozen, Cassavetes also directed independent films that rejected studio money and influence in favor of emotional honesty. “I don’t care if it’s going to be a success,” he said in 1978, promoting his Opening Night. “I want those suckers to come in there and to see this movie, because they’ll see what they always wanted to be.”

Ritter, who died in 2003, played the male lead in ’70s TV comedy Three’s Company, the voice of Clifford the Big Red Dog, and a gay dollar-store manager in the Billy Bob Thornton drama Sling Blade. In his appearance in season two of The Larry Sanders Show, Ritter gets in a fistfight with critic Gene Siskel on the day when an Entertainment Weekly reporter comes to profile the show.