Dave Matthews Band is generally not considered cool anymore. Almost certainly, it never was in the downtown New York world of which the actress and writer Greta Gerwig has become a cool-girl-real-girl avatar in recent years. But in a time and place (America’s vast, yearning middle-class suburbs, in the cultural desert of the Clinton and early Bush years) and to a certain kind of person (such as a teenager aching for the jazz-adjacent cred that jam-band fandom could provide but more comfortable with white ball caps and lacrosse than ponchos and hallucinogens), Dave Matthews Band was Bob Dylan in Greenwich Village in 1966. And so there is a crucial moment in Lady Bird, Gerwig’s solo directorial debut, in which the title character, a Sacramento high-school senior in 2003, confronts the cruelest heartbreak imaginable to her by blasting the band’s ballad “Crash Into Me”: “Sweet like candy to my soul / Sweet you rock and sweet you roll.” The result is both sympathetic, and very funny.

“There was no other song it ever was going to be,” Gerwig said. “In preproduction, I realized I didn’t know what I was going to do if Dave said no [to its use]. I wrote him a letter. ‘Dear Mr. Dave Matthews … ’ ”

Gerwig was sitting at a small corner table near the window at Morandi in the West Village, not far from where she lives with the filmmaker Noah Baumbach. “I thought it was a really romantic song when I was a teenager. I would listen to it on repeat on a yellow CD player,” she said. “I couldn’t imagine a world in which a guy would feel that way about me.”

Maybe it was because of her sexy dirndl skirt of a name, maybe because of her squinting physical resemblance to indie Gen-X avatar Chloë Sevigny, maybe simply because of her distinctive delivery. But since the very beginning of Gerwig’s career, she has been a generational lightning rod of sorts. As what the New York Observer once called “the Meryl Streep of mumblecore” — the hyperlow-budget late-aughts movie movement led by directors like Joe Swanberg and the Duplass brothers — Gerwig was near-instantly labeled an “It” girl and invested with all sorts of theories about what her success and acting style meant. Her brand of hipness was confusing — was she really that earnest? Were they all that earnest? How could that possibly be cool? Critics, especially those of an older generation, were suspicious.

She was, unmistakably, a gifted actress. But the Guardian also called her “the poster girl for wayward, brittle middle-youth,” a “galumphing work in progress.” In The New Yorker, Ian Parker wrote that, despite having a “precise, literate mind,” Gerwig “has the air, not uncommon among her contemporaries, of having swallowed a very low dose of LSD.” “Ms. Gerwig, most likely without intending to be anything of the kind, may well be the definitive screen actress of her generation, a judgment I offer with all sincerity and a measure of ambivalence,” A. O. Scott wrote in the New York Times. “Part of her accomplishment is that most of the time she doesn’t seem to be acting at all. The transparency of her performances has less to do with exquisitely refined technique than with the apparent absence of any method.” And then there was this sort of thing: “While watching Greta Gerwig on screen, you might be tempted to kiss her,” wrote Stephen Heyman in T in 2010. “This is not meant purely as praise. Gerwig, 26, plays characters who are given to discursive verbal forays with oodles of ‘ummmms.’ So planting an unexpected kiss would not only be a recognition of her adorableness but also a useful way to shut her up.”

In a way, then, Lady Bird, a remarkably self-assured debut, feels like a rebuke. Or at least an assertion of artistic intent. At 34, and moving, finally, behind the camera, Gerwig is exiting the phase of her life where she’ll be asked to represent a mysterious, fascinating rising generation. The winds have shifted some, and the microgeneration after her is just as earnest (or more so) but culturally preoccupied less with its own emotional wanderings than with larger political questions of identity, and of race. Gerwig seems still to be considering, and even reclaiming, some of the traits that hers has been tagged with: nostalgia, that earnestness, parental attachment. In other words, what does it look like onscreen when millennial sincerity is treated not with mockery or puzzlement but with, well, sincerity?

Gerwig appears to be a genuinely sincere person, a kind of spiritually permanent college student, in a way that might get under the skin of someone with more ironic armor. She wears a giant Hello, Dolly! sweatshirt and an even more giant backpack. She references Tina Fey’s Bossypants like scripture and listens to podcasts about entrepreneurship (“The one about the woman who created Spanx made me sob”) and religion (“Krista Tippett” — the host of On Being — “is like my fucking queen”). She quotes Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel to express her sadness over the Harvey Weinstein mess: “In a free society, some are guilty; all are responsible.” She goes to church sometimes, and though she doesn’t subscribe to any particular denomination (“The Catholic theatrics are pretty high quality, but the Protestants have better hymns”), she’s really into the Quakers right now: “There’s nothing that you have to believe or avow. The only thing you have to believe is that the light of God exists within each person.” She really, really loved her single-sex education, both the high-school portion and at Barnard, where she was delighted to discover that all the doctors at the health center were gynecologists and enjoyed her time on the parliamentary debate team.

Gerwig’s enthusiasms extend also to Zumba, but what she really likes is a barre class run by this one woman from Portland, Oregon, whom she admires for her “body positivity,” and on the day we first met, she was, with some embarrassment, about to try something called the Class, in which Tribeca women combine burpees and cathartic screaming. “It seems like maybe the fitness equivalent of the toy poodle,” she said. “Like, you have to admit that you love them and you want one that’s tiny. You’d rather be the girl who has a German shepherd who goes for a run. Not one with a fluffy piece of lint who goes to a place where you chant with crystals.” She considered. “Before they poured the floor at the studio, I read, they put rose quartz everywhere, and I was like, I mean … I can get down with that.” She has a friend who works for Moon Juice, and so she speaks highly of its sprouted almonds, even if “I always thought it was kind of ironic when she’d be stressing out about the moon powders.”

The author and illustrator Leanne Shapton, who knows Gerwig and Baumbach from the neighborhood, spotted Gerwig and stopped to chitchat. Shapton, as it turned out, designed the font for Lady Bird’s title and credits: “She made an entire uppercase and lowercase alphabet and painted it ten times the size that it needed to be and shrunk it down so it looks like a font but has enough imperfections so there’s a density,” Gerwig told me after Shapton had walked away. “I feel like movies are presents, and credits and fonts are bows and wrapping paper.” She paused. “I like everything to feel like it was given a lot of time. I hate it when I watch movies and it seems like they just went and picked a font and, like, called it a day.” She paused again, considering Shapton. “I also have a crush on her because she’s very beautiful. She is cool in the way that everyone wants to be, but she’s also a real person.”

“I’ve made so many films in New York,” Gerwig said, that “there was an assumption I think a lot of people had that I am a New Yorker, that I am from New York, and I always felt like nothing could be further from the truth. I’ve done a good job of convincing you, but I’m not, as so many people who live in New York are not.”

Lady Bird, which is also Gerwig’s solo writing debut, is the story of a high-school senior (Saoirse Ronan) at an all-girls Catholic school in Sacramento who longs — despite her average grades — to be the star of the school play, to go to college on the East Coast, to be extraordinary. Though her name is Christine, she insists on being called “Lady Bird,” a pretension with which her salt-of-the-earth parents — a nurse and an out-of-work computer programmer, played with extraordinary sensitivity by Laurie Metcalf and Tracy Letts — comply. (It’s a complicated dynamic: Metcalf calls the mother character “totally passive-aggressive.”) The plot is a gentle one. Lady Bird acquires a couple of boyfriends (each recognizable as a classic type who might appeal to a smart-in-some-ways, really-not-in-others teenage girl), chases acceptance from the popular crowd, applies to colleges her family can’t afford to send her to.

Gerwig attended an all-girls Catholic school in Sacramento, with parents who worked as a nurse and a loan officer at a credit union, who sent her off to an expensive East Coast college, and although the movie has been widely discussed as a roman à clef, she says it’s not. For starters, Lady Bird is set in 2003, Gerwig pointed out, and she graduated in 2002. “I never made anyone call me another name. I never had dyed-red hair. She’s so much more wild and outspoken, and I think I was only ever that way in my head. In a way, I felt like I kind of put into her the sheer confidence and the id I find in 8- or 9-year-old girls. They’re just brash, and they don’t know that they should feel anything but great about themselves.

“When you write something you know, you’re making a story that will work, whether or not there’s bits taken. It’s always funny to me when people say, ‘Well, it’s clearly autobiographical,’ and I say, ‘Well, how do you know my autobiography?’ ” she continued. “Certainly, there are things that are connected, but I just think it’s a very interesting assumption. In some ways, it feels akin to the assumption that I’ve experienced as an actor when people say … ‘This is you.’ Which I’ve always taken as a compliment because it felt like you were watching a person.”

The teenage Gerwig was an extensive diarist, but she didn’t look up her old journals until after she’d finished the script, called “Mothers and Daughters” in a first draft that clocked in at 350 pages. (“It originally had a lot more dances,” she said.) When she opened the old pages, she was pleasantly surprised to find that she’d accurately remembered some of the tiny details — the rumor that clove cigarettes had fiberglass in them, the very fact of clove cigarettes at all — that make the movie so spot-on evocative of high school. But mostly it was the vividness of her feelings that struck Gerwig. “I would go on for pages and pages about this crush I had, dissecting every moment. ‘Did he notice that our arms were touching, or was that an accident?’ And then I wrote, ‘Upon further reflection, I think that this might’ve been a more vivid emotional experience for me than him.’ I was like, Oh, honey, nothing you’ve written is more true.”

When Gerwig was young, her parents made a point of taking her to local Sacramento theater — she proudly ticks off the names of the companies, and the playwrights whose work they put on, and even the directors. At Barnard, where she studied playwriting, she became a Kim’s Video devotee, methodically working her way through the director-organized shelves. (It was Claire Denis’s film Beau Travail, she said, that made her shift her focus from theater to movies.) She rejected traditional paths like law and medicine. “Chekhov was a country doctor, spent all his time with people and in their homes. I was like, Well, that’s good, and then I was like, Well, I’m not interested in it, and also I don’t like blood, and there are no country doctors anymore,” she said. “The idea that I would become a doctor to become more like Chekhov is a pretty circular route.”

After college, Gerwig lived all over Brooklyn — East Williamsburg, Prospect Heights, deep Park Slope, or “Park Slide,” as she says fondly. She had odd jobs, including at the Box, the Lower East Side cabaret, and began working with Swanberg, whom she had met through a college boyfriend and who was making interesting movies that were unlike anything that had been done before, for almost no money.

Mumblecore was a big deal, for a small movement, in part for what it seemed to reveal about a certain slice of young, college-educated, mostly white people trying to figure out how they related to the world. It was hailed in the Times as something that “bespeaks a true 21st-century sensibility, reflective of MySpace-like social networks and the voyeurism and intimacy of YouTube. It also signals a paradigm shift in how movies are made and how they find an audience.”

Gerwig now physically cringes at the mere mention of the word mumblecore. “I just hate it,” she said. “It feels like a slight every time I hear it. Because of the improvisational quality of those movies, and the fact that everyone was nonprofessional, I have had a bit of an uphill battle just to say ‘I know how to act.’ I didn’t stumble into this. I wasn’t just a kid.” But she credits her roles in those films — Nights and Weekends, Hannah Takes the Stairs, Baghead — with helping teach her to write. “We called them ‘devised films,’ because we’d know the characters and what was supposed to happen in the scenes but not the words. It was a way of writing while I was acting.”

It was also that set of films — which made a bigger splash in the indie-movie scene than in the culture at large — that put her on Baumbach’s radar. (He actually recommended her to his agent before the two had ever met.) When Baumbach cast her in 2010’s Greenberg, released when she was 26, it was her big break. Shortly after he divorced his wife, the actress Jennifer Jason Leigh (Gerwig had trained for the role, in part, by working as an assistant to Leigh’s mother), the two began their romance. Baumbach and Gerwig turned an email correspondence into a project: The duo co-wrote Frances Ha and Mistress America, both starring Gerwig and both markedly sweeter than anything Baumbach had worked on in the past. “I liked what she was writing so much that it made me work harder with my own to impress her,” Baumbach said.

This collaboration led to a spate of headlines referring to Gerwig not as a partner on the works but as their muse. “The actress Greta Gerwig has had the same liberating effect on Noah Baumbach as Diane Keaton had on Woody Allen: she has opened him up, lending his films a giddy sense of release,” went one typical summation in the Economist.

“I did not love being called a muse,” said Gerwig bluntly. “I didn’t want to be strident about it or say, ‘Hey, give me my due,’ but I did feel like I wasn’t a bystander. It was half-mine, and so that part was difficult. Also I knew secretly that I was engaged with this longer project, and wanted to be a writer and director in my own right, so I felt like the muse business, or whatever it was, was a position that I didn’t identify with in my heart. But I think one thing I learned early because of the group of movies that are called mumblecore” — she slowed down, a little archly, over the word, to acknowledge again her discomfort with it — “is not to attach too much to the moment you’re living through from a press perspective. I also had this sense of, Well, they’ll just eat their hat one day.”

TV was one idea when Gerwig hit a dry spell with acting gigs after making Frances Ha and Mistress America. “I felt like I had done things that I was incredibly proud of and I felt like I had authorship over, and done good work as an actor, but my wheels weren’t catching purchase with whatever the Zeitgeist was,” she said, forking her pasta. It was a curious double identity as an actress — plausibly the face of a generation, particularly of the privileged of that generation, and, just as plausibly, a near-anonymous actress who hadn’t yet made anything that any real number of people had actually seen. She met with the producers behind How I Met Your Dad, a planned spinoff of the long-running, quietly beloved CBS sitcom How I Met Your Mother, and signed up for the starring role, along with a writing role. “It felt like this incredible lifeline for me. It felt like a place to give myself some structure,” she said of what looked from the outside like a bit of a career swerve. Not to mention that she was told it was a “sure thing.” The pilot wasn’t picked up. “They send the shows to Vegas, and people sit there with knobs, and they turn the knob down if they don’t like an actor,” Gerwig explained with a little embarrassment. “Nobody exactly told me I tested low, but it was insinuated that America did not like it.”

But that allowed her to turn to directing. “By the time I started, I felt like I had ten years of training. My film school was as an actor and co-writer and co-director, and whatever else I did, which included costuming, and holding the boom, and editing. It was a way for me to get my Malcolm Gladwell hours in.” She also benefited from more targeted instruction, in recent years, from DPs who’d heard she wanted to direct and let her sit with them while they constructed their shots. “When I finished the script, I had a moment with myself where I thought, You’re either going to do this now or you’re never going to do this,” she said. “Now you have to make your mistakes and get your gifts because you have to, at some point, jump. I think a lot of women have also particularly a need to feel that they can stand in their own expertise before doing something. A lot of my female friends will be so overqualified for what they do that by the time they do it, it’s like, Well, obviously.”

During the press tour for Mistress America, a journalist asked about whether dating Baumbach, and then writing with him, had opened certain doors for her. Gerwig acknowledged that perhaps it had, proximally, but refused to concede the larger point. “I don’t mean to sound annoying,” she told the reporter, “but I would have done it anyway. I will find that one door and then push it wide open. I’m lucky to find collaborators and kindred spirits. But I don’t need a man, and I would have done it anyway.”

A confident, direct version of ambition is another generational trait that Gerwig seems to comfortably inhabit. Recently, she saw Saoirse Ronan in London to promote the film; Ronan told her she was beginning to think about whether she could direct, inspired in part by watching her on set. “Greta is the one that I’d want to emulate,” Ronan told me. “She was incredibly clear about what she wanted but also supportive about finding our own way through the characters. We’ve been talking in a practical way, too, about stories that I’d like to do and if I could work with her in that regard. She’s a great one for the advice.”

Ronan was also struck by Gerwig’s actorly approach to directing. “She had very clearly mapped out each character’s journey, what it would be like to be a kid in post-9/11 America in California, how complicated it would be to think about leaving Sacramento for the first time,” but also “she gave us an awful lot of freedom to incorporate our own selves.” Gerwig even gave Timothée Chalamet, who plays one of Lady Bird’s love interests — a self-styled high-school intellectual — a syllabus for “what a paranoid anarchist type of thinker would have been reading back then,” he said, which included, in addition to the requisite Howard Zinn that shows up in the movie, The Internet Does Not Exist, an essay collection that warns of the dangers of a networked world. She also asked him to watch Eric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s, which she told me contains a character who is an example of a long-standing type: “These guys who are just completely stuck on their ideas, whether music or progressive philosophy or whatever it is. Like, ‘I’m going to train you to like Pavement.’ ” Gerwig also gave specific directions on how to play the many comic moments in the script: Humor was to be achieved not through comic acting but by playing the situation with all the seriousness with which a high schooler would feel it. “I like things that are funny,” Gerwig said, “but I don’t like things that are in quotes.”

Gerwig plans to tip the balance of her work going forward more toward writing and directing (though she’d like to keep acting). “You just stay in it long enough, and eventually you’ll just be old.” Nobody will worry over whether you are an actor or a director or a writer. “Everyone will just think, Oh, she’s such a wonderful 75-year-old now. She’s our lady Clint Eastwood.”

She has one script, something she wrote before Lady Bird, in the drawer, but for her next project, “I have an inkling of wanting to make something that’s more silent, literally fewer words.” She wouldn’t give any more detail, however. “I worry if I put an idea out in the sunlight too early, it shrivels, and I don’t want to shrivel anything right now.”

Baumbach’s most recent film, The Meyerowitz Stories, was released on Netflix and in theaters just a few weeks before Lady Bird, which comes out on November 3. Both movies open with a parent and child, driving together, on the cusp of the difficult moment when college is about to force that relationship into its next, more distant, phase; both puncture the sweetness of the scene by someone melting down immaturely. In Baumbach’s film, it’s the parent. In Gerwig’s, it’s the daughter.

With Mistress America and Frances Ha, said Baumbach, the pair were able to create “a synthesis” of their two voices, “a kind of a third thing that allows you to try different selves on.” But the couple have strikingly different tones to their independent work, although they tread the same thematic ground (and give each other notes on drafts). Family, in much of Baumbach’s filmography, has been a source of neuroticism for his protagonists, often children picking up the pieces, learning to overcome the limits of a selfish, immature parent’s love. Lady Bird, by contrast, is about a child failing to recognize, in the moment, the expansiveness and totality of her parent’s love for her — as well as the complicated dynamic between teen girls and their mothers, even those who are fond of each other. Baumbach, though, sees their emotional truths as more related. Both movies, he said, are about “how hard it is to acknowledge positive things in someone you need to move away from, and how hard it is to leave.” Gerwig’s story is, in her phrasing, “a movie about wanting to leave a place that’s secretly a love letter to the place, and a movie ostensibly about a daughter that’s secretly about the mother.”

“Oh, I’ve got a lot of guilt,” Gerwig replied quickly when I mentioned that I had seen the film as, in part, a meditation on that particular emotion, and how deeply it can become intertwined with love. “We always joked that we should put up a title card at the end of the movie that said CALL YOUR MOTHER,” she said. The guilt kicked in. “I need to call my mother.”

Gerwig showed her parents and friends the script before shooting and screened the film for them before it premiered, but she also spent a lot of time considering how she’d treated her mother as a teenager. “I could only see the faults in clear relief, but as I’ve gotten older, it’s like, Goddamn, she was right about almost everything.”

For all that she insists Lady Bird isn’t exactly her own story, it feels like a coming-out of sorts for Gerwig’s own sensibility, her preoccupations. “I only ever write from a place of love,” said Gerwig, “which sounds goofy but is actually true. Some writers write from a place of anger or analysis, or something that feels more didactic, but that impulse means that I also write out of real love, which is complicated and changing.”

“Sincerity means a lot to me,” Gerwig continued. “Actually, in Frances Ha, at the beginning, she’s reading out of a literary-criticism book called Sincerity and Authenticity. Basically, the question she’s setting up is, what do we mean by sincerity, and does it diminish the thing?” She considered. “But I’ve always felt like it heightens it.”

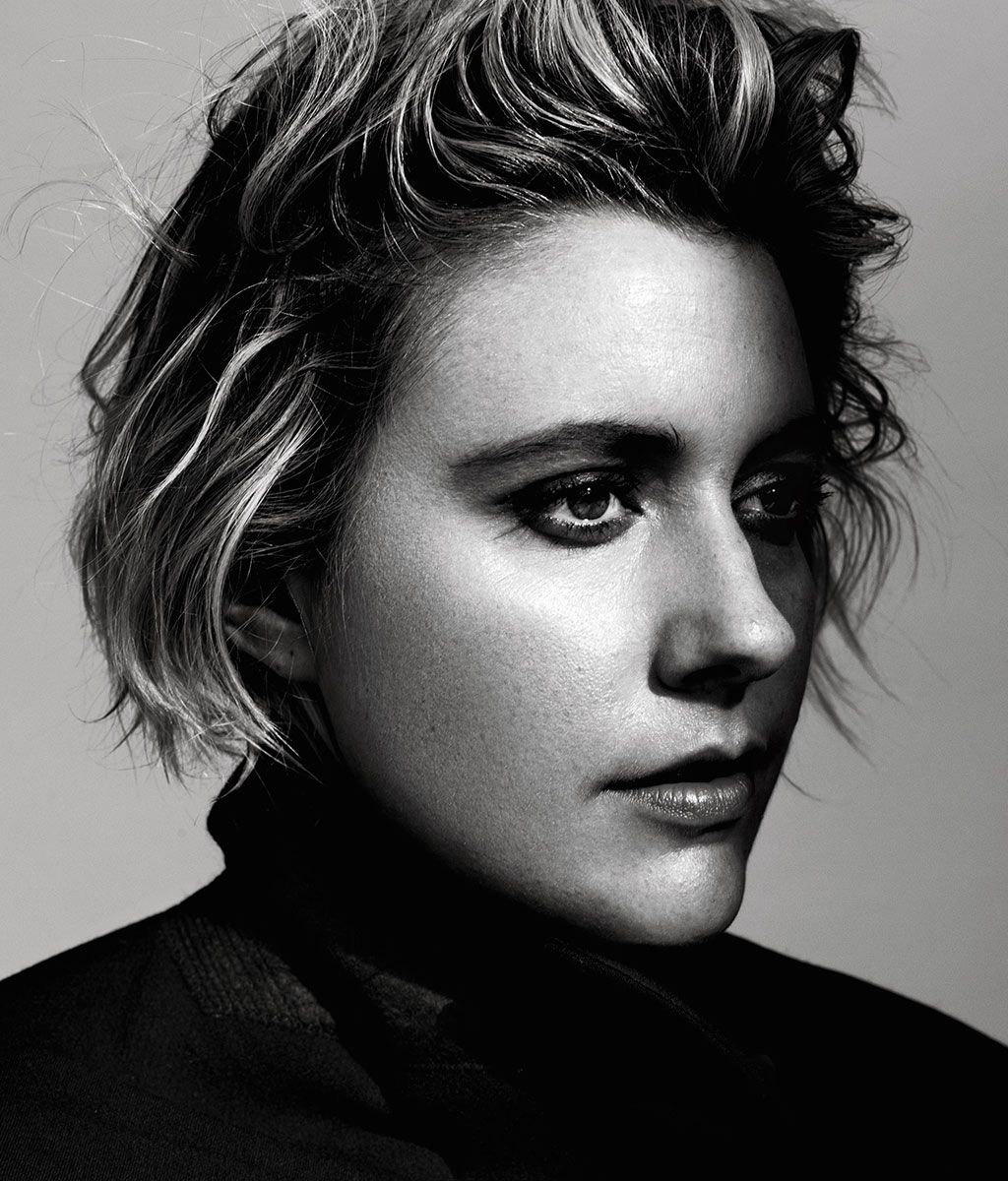

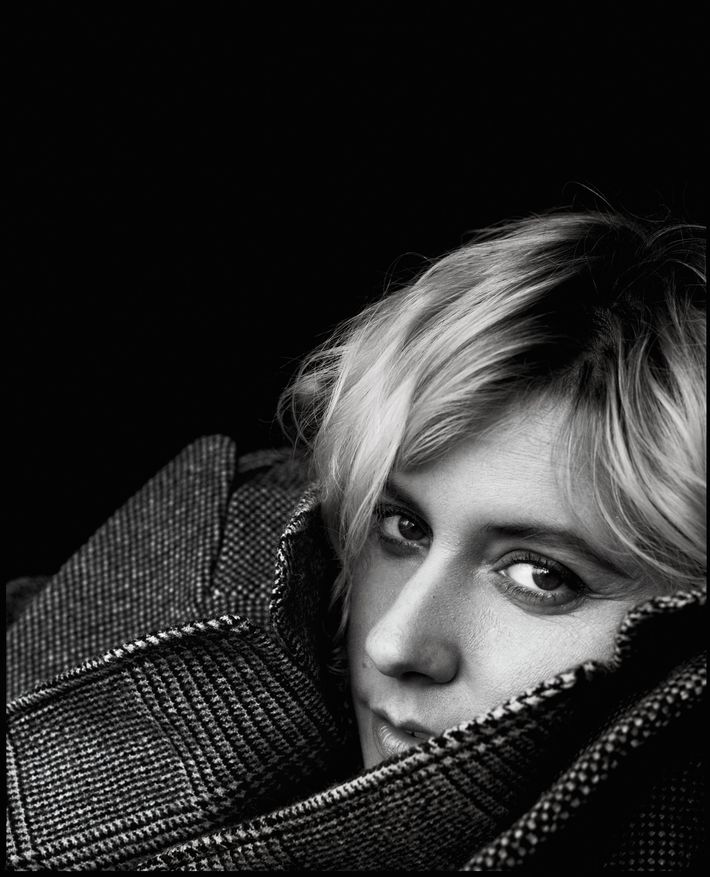

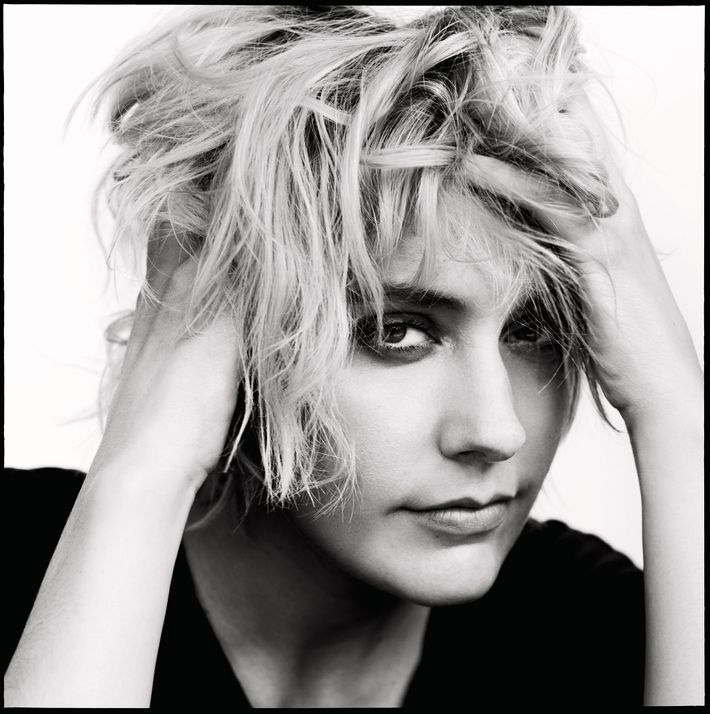

Production Credits: Photographs by Norman Jean Roy; styling by Bill Mullen; hair by Marco Santini for Ion Studio at Tracey Mattingly; makeup by Alice Lane using Milk Makeup at The Wall Group.

*This article appears in the October 30, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.