One of the most striking details about the storied lawyer and first black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, is from a professor at the University of Maryland law school. He described him as the kind of man who in his youth “wore life like a loose garment.” When researching Marshall’s early years, this detail struck me, because it contradicts how pivotal civil-rights figures are often portrayed in Hollywood films — staid, sanitized men and women hyperaware that they are making history.

Marshall, the Reginald Hudlin–helmed film starring Chadwick Boseman, falls into the trap of flattening its titular character, choosing to render him as a hollow legend in the making rather than taking an interest in who he was as a person. The film centers on an early case in Marshall’s long career from 1941, when he was in his early 30s. He crisscrosses the U.S. as a traveling lawyer for a struggling NAACP, under the guidance of Walter Francis White (Roger Guenveur Smith). The case brings him to Greenwich, Connecticut, to defend a black chauffeur with a sullied past, Joseph Spell (Sterling K. Brown), from a rape charge leveled at him by his white employer, Eleanor Strubing (Kate Hudson). It’s actually a Jewish insurance lawyer, Sam Friedman (Josh Gad), who defends the case, as Marshall isn’t allowed to even speak in the courtroom — he’s forced to only advise by the hostile Judge Colin Foster (James Cromwell), who just so happens to be a family friend of the prosecutor.

The film gestures at that striking quality I discovered in reading about the real-life Marshall: Boseman grants the man a distinct swagger and forceful sense of humor, seemingly designed to rile white people and disabuse them of their preconceived notions about him. A scene at the very end of the film — after Marshall has moved on to a new case in the Deep South — shows him drinking from a whites-only water fountain, an older black man looking on in shock at his brazenness. It’s supposed to be a humorous and cutting moment, nodding to how Marshall is in a class apart from others around him. It only reminded me how little effort the film makes in understanding why Marshall makes such bold decisions on a deeper level, and who he was beyond this arrogant, quick-witted man it presents.

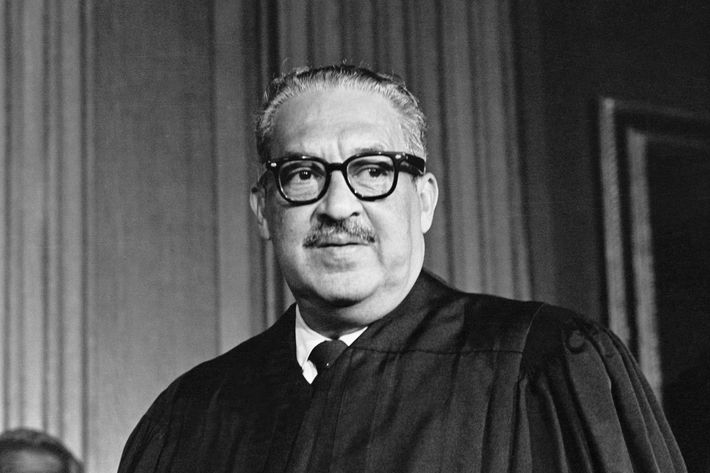

Marshall’s filmic characterization ultimately comes down to big speeches on courtroom steps, a lot of swagger, and little else. But the issues with the film are apparent long before Marshall ever makes a grand speech about the power of the law. All you have to do is look at Boseman to see that this film has a blinkered view of history and blackness: The real-life Marshall was a light-skinned man, and his place on the color spectrum undoubtedly influenced how he became such a legend.

American film often flattens pivotal black figures, treating the experience of blackness as if it has no particular textures or contradictions. In Hollywood movies, racism is something we all experience in the same way, which couldn’t be further from the truth. This is often clearest when it comes to issues of colorism, which stretch across the black diaspora, as well as other communities of color. In reality, being of a lighter complexion grants a level of privilege in moving through the world, while being of a darker hue is derided, aligned with its own noxious stereotypes about intellect and sexuality, and can play a factor in prison time. The issue of colorism is multifaceted and wide-ranging, touching on a host of complex issues — the history of how some black people have passed for white, how lighter-skinned black women are deemed more beautiful because of a perceived proximity to whiteness, internalized racism. Typically, films will cast lighter actors in roles they are ill-suited for. Remember when Zoe Saldana was burdened with laughable prosthetics and darker makeup in order to play Nina Simone last year? Marshall is a rare example of the opposite happening, but it’s just as insidious — it signals that the film deems colorism, and the way it touches Marshall’s life, as inconsequential to blackness and the history it seeks to untangle.

Being light-skinned granted Marshall access. Marshall was aware of the effects of colorism, thanks to stories he’d heard growing up from his father — a man light enough that he could pass, but chose not to — and an incident in his high-school years, in which a brawl broke out when a man called him a “nigger” and his Jewish boss had to bail him out of jail. It’s hard to imagine his light skin didn’t have a role in his survival of this incident, giving him access to jobs in which a white boss would even be willing to defend him.

This isn’t to say that Marshall didn’t experience racism. He was a still a black man who looked like a black man, and white people were quick to remind him of it. Just look at what Marshall experienced during his confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court: At one point, committee chairman James Eastland, a Democrat from Mississippi, asked Marshall if he was “prejudiced against white people in the South.” But in watching the film, I couldn’t help but notice how better suited Boseman’s co-star, Roger Guenveur Smith, would have been for the role, if it were a story about Marshall later in life. Smith is cast in the movie as Walter White, a man who could easily pass — something he used to advantage whenever traveling to the South. In his autobiography, White wrote, “I am a Negro. My skin is white, my eyes are blue, my hair is blond. The traits of my race are nowhere visible upon me.” (Smith may be light-skinned, but under no circumstances could I see him ever being able to fully pass as a white man.) Marshall and White dictate, in dramatically different ways, how entrenched colorism is, and also how it exists on a continuum: Marshall may have been light, but he could not pass and move through the world in the ways White did. It’s a shame the film doesn’t explore these dynamics.

Marshall’s refusal to grapple with colorism is quickly revealed to be a symptom of a larger problem — its blunt understanding of race and utter disinterest in Marshall himself. In ignoring the lived reality of colorism, Marshall creates a circumscribed version of blackness that’s easy for white audiences to consume, lacks any sort of challenging narrative, and bypasses the more fascinating wrinkles in its characters’ lives. Despite his name being its title, the film doesn’t care about Marshall so much as it does Sam Friedman — it’s his journey from reluctant lawyer to ally that proves to be the true bedrock of the film.

Sure, there could be an interesting narrative developed from interrogating how two very different communities — in this case, blacks and Jews — handle bigotry and come together. But that the first major biopic about Marshall pushes him to be a supporting player in his own story — and instead explores Friedman’s Jewish faith, marriage, and ultimately, the importance of his allyship — is insulting. Marshall’s impressive legal mind is nowhere to be found in the film. Yes, he’s shown capably helping Friedman. Yes, he’s shown using whatever venue he’s in as a stage, facing press and protesters from the community, who hold signs riddled with slurs, with a confident disposition. Ultimately, though, the film doesn’t answer the one question necessary to make this biopic work: Who was Thurgood Marshall, really?

Film isn’t necessarily responsible for teaching people a history they aren’t already curious about. But it would be ignorant to act as if film — Hollywood and otherwise — doesn’t reflect, reimagine, and sometimes even reshape the world we inhabit. In many ways, Hollywood history is American history. It tells us what we value, what we ignore, what we choose to glorify. What Marshall chooses to ignore — despite having a black director — is how being light-skinned shaped Thurgood Marshall’s path in life. It also refuses to grapple meaningfully with who he was. He’s painted instead as a dashing, sometimes wry symbol in a three-piece suit. If there’s anything that registers from watching civil-rights biopics of this ilk, it’s that while grandiloquence makes the legend, it is minutiae that informs the man.