One of the earliest, most intriguing images that appeared in trailers for Blade Runner 2049 was that of Ryan Gosling walking toward an enormous head of a female figure, in the irradiated ruins of what appeared to be Las Vegas. It was striking because of its graphic starkness, and its comparative lack of visual resemblance to anything in the original film; it was director Denis Villeneuve’s first shot across the bow to prove what this visually iconic universe might look like in his and Roger Deakins’s hands. Later trailers revealed the giant women to be a running visual theme in the Blade Runner universe’s late Sin City, with eerie shots of dust-covered, gargantuan nudes frozen in submissive poses, as if the people behind the Korova Milk Bar had been given a substantial public art grant circa 2025.

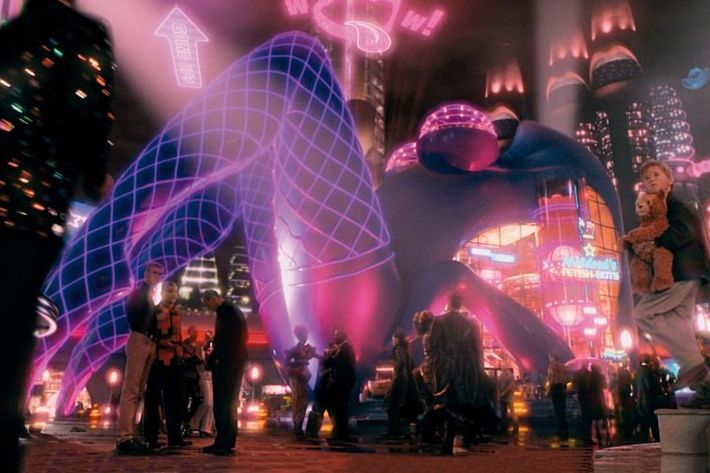

Even before the film’s release, this imagery placed Blade Runner 2049 in an existing realm of sci-fi imagery. If we could see its future Vegas in its heyday, it might look something like A.I.’s Rouge City. The neon-lit den of vice from Steven Spielberg’s critically divisive sci-fi fairy tale is a place where seemingly every desire can be satisfied; one can procure the services of a robot prostitute, or step into a booth where Robin Williams Googles stuff for you. For David (Haley Joel Osment) an android boy preoccupied with winning back the love of his mother, Rouge City is full of maternal possibilities, as evidenced by the giant pair of splayed female legs that welcome him at the entrance.

Ever since Metropolis’s men of science and industry gazed up at the gigantic bust of mother figure Hel, the future cities of the cinema have had a thing for giant ladies. (To be fair, Joel Schumacher notably also threw some giant men into his vision of Gotham City, to the extent that Batman is a work of cyberpunk.) It makes sense that colossal human figures would play into our visions of cities on the brink of collapse; we know how these figures will look in pieces, brought low and made to rest in a museum. Bigness goeth before destruction, etc. But unlike Constantine and Nero, political figures whose likenesses rose up to a hundred feet over Rome, we keep imagining a future where our cities’ colossus budgets favor frequently nude, nameless women.

The first, and most obvious, observation is that these are commercial images, and the fallout of commerce run amok is a cornerstone of cyberpunk. The iconic LED geisha munching candies on the side of a skyscraper in the original Blade Runner has turned into four-story ballerinas and naked holographic girlfriends in 2049, walking commercials that stalk Los Angeles like benign Godzillas. They’re women, because looking at women is a universal pastime; they’re sexualized, because sex sells, baby. The idea is retro-echoed in the opening credits of Mad Men, in which a silhouetted ad exec falls past a cityscape wrapped top-to-bottom in the images of larger-than-life women hawking perfume and nylons and the dream of a better life.

The idea of explicit imagery getting past the standards boards of the future is another part of the dystopian fantasy: The line of history is leading inexorably to a godless future where everything is sexy all the time. Cinematic inventions like Rouge City and its ilk exist on an exceedingly well-worn trajectory where religion and sexual repression sit at one end, and scientific innovation and female objectification exist at the other. “You can’t have one without the other,” male filmmakers tell us with a solemn, regretful shrug. I’d take a wild, semi-educated guess that future-city movies are second only to Westerns for scenes set in brothels and red-light districts. (Hence the very successful synergy of Westworld.) But figures of the scale and visibility of Blade Runner 2049’s ad girls are supposed to represent something closer to the mainstream. We can infer, then, that there are no people (i.e. women) in this future world who would raise their hand in the planning meeting and point out that the latest Joi ad campaign, yes, looks wicked tight, but is kind of stupid.

But why does she have to be so big? Not for nothing, but there is a very real thing called macrophilia, which is a fascination and lust for gigantic, multistory-high women. (They are almost uniformly women; gay male and hetero female macrophiliacs are either rare or don’t spend as much time online.) It’s not exactly a fetish, since consummation is physically impossible; it’s something confined to the realm of imagination, mostly in art shared in various giantess (or GTS) message-board communities, aided by the power of PhotoShop. An adventurous search leads to countless images of tiny men being picked up and played with by enormous, scantily clad women, crushed between their toes, or crawling into their orifices like an X-rated Innerspace. Naturally, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is a seminal text for the community, as is Gulliver’s Travels.

So does Blade Runner 2049 harbor some latent macrophilia? In a 1999 Salon article on the subject, a psychologist asked for comment guesses that the fantasies of GTS aficionados might have something to do with a dominant mother figure in their past. That all seems a little Freud for Dummies, but then again, it’s hard to see anything else when A.I.’s David, obsessed with his mother to the eventual point of self-destruction, must enter the huge, parted red lips of Rouge City’s blow job–themed bridge in order to find the secret to being her son once again. And that’s to say nothing of Ryan Gosling’s K, whose entire adventure in 2049 begins with the discovery of a dead mom in a box, and is fueled by the possibility that she actually might be his dead mom. As he wanders the rainy forever-night of Los Angeles, thinking about his dead robot mom, he’s rendered embryonic next to the giant holographic women that pirouette and pout above him.

There are a wealth of female characters in Blade Runner 2049, and at least a couple are complex, dramatic creations. (I’m sure Robin Wright’s no-nonsense Lt. Joshi has some hot takes about the state of outdoor advertising that she’d share over a whiskey or two.) But Villeneuve’s film is ultimately obsessed with motherhood and the ability to reproduce over any other defining female trait, and feels less interested in questions of consciousness than in the pursuit of an elusive pseudo-religious special baby. This is not a film that was ever going to be interested in anything but familiar, even old-fashioned sexual politics, and I don’t want to spend too much time criticizing Villeneuve for his performance in a game he clearly wasn’t even playing. I just mean to point out that his use of female bodies as figureheads, these massive gaping-mouthed infertility idols, are not empty or neutral creative choices.

2049 might not be outright misogynist, but it does have a rather transparent mommy complex, even if in the end K doesn’t actually want to crawl inside a giant lady. It would certainly make for a great image, though, and I’d bet money somewhere on the internet someone’s working on bringing it to fruition. As 2049’s unforgettable three-way sex scene and the vibrant creations of the giantess community proves, just about any fantasy is possible with the right technology at your disposal.