In TV, movies, and real life, women have been at the forefront of the year’s biggest stories — so this Halloween season, we’re looking at pop culture’s most wicked depictions of female power.

In 2000, nu-metal band Papa Roach released a video for the song “Broken Home.” It’s about the fallout of a divorce, and like Papa Roach’s previous single, “Last Resort,” it was written specifically to appeal to teenagers going through very real emotional trauma. In one scene in the video, lead singer Jacoby Shaddix scream-cries while pounding the ground and grabbing fistfuls of sand next to a forlorn tire swing. Say what you want about “Broken Home,” or about nu metal in general, but Papa Roach were huge for a reason, and that reason has to do with their ability to convey the illusion of uncontrollable emotion. In other words, sad songs like “Broken Home” sell sadness, and when they’re successful, it’s because the sadness feels real.

Witch house, a subgenre of electronic music, sounds nothing like Papa Roach, but it was able to convey unfiltered emotion in similar ways. It was successful because it sounded sort of terrifying, and it was briefly popular — from 2009 through a little bit of 2010 — because everyone wants to be a little bit terrified sometimes. The genre’s day in the sun went by so fast that most of the artists lumped into it didn’t even have time to release an album during its short-lived heyday. Still, witch house was popular because it sold a mood — an unsettling mix of sadness, melodrama, fear, and paranoia — and if you made music that could be lumped into that weird mood mixture, then you, too, could become a practitioner of witch house. The problem was, no one could quite settle on what witch house was supposed to be, but everyone was sure they didn’t want to be part of it.

With the benefit of distance, it feels fairly obvious which bands were witch house and which were actually just experimenting with electronic music. At the time, though, the genre was appropriately murky. If you had a symbol in your name, you were witch house. If you made music anonymously, you were witch house. If your music had drums that sounded like they’d be more at home on a Three 6 Mafia song, you were witch house. The reality was that witch house was a blend of a couple of different musical ideas: shoegaze mixed with an admirable reverence for the psychedelic, chopped, and screwed mixtapes of Houston’s DJ Screw. Blurry synth and guitar tones were stretched and reversed, and vocals, if they existed at all, were largely unintelligible, mangled and slowed into a soupy moan.

The origin of the name is not as clear as it probably should be. The dominant story is that Travis Egedy, a Denver musician who records as Pictureplane, came up with the name as a joke in 2009. “Witch house” stuck because no one else could figure out what to call the dark electronic music that had cropped up as a reaction to the zonked-out stoner jams that were championed by chillwave artists like Washed Out. Other names also floated around, like “drag,” referring to the way sounds were stretched to the point of distortion, before the deeply regrettable period when musicians Lauren Flax and Lauren Dillard, who at the time were playing music as Creep, jokingly listed the genre as “Rape Gaze” on their Myspace page. In a 2010 Village Voice interview, Flax explained how it was a joke taken out of context. After the interview was published, she wrote in to explain further:

I just wanted to add something. I definitely didn’t express enough that we do not take the term “rape” lightly and would never want to advocate sexual violence against any human being. It was a play on words which we never expected to be used as an actual genre. If there is anyone out there that we may have offended, we sincerely apologize.

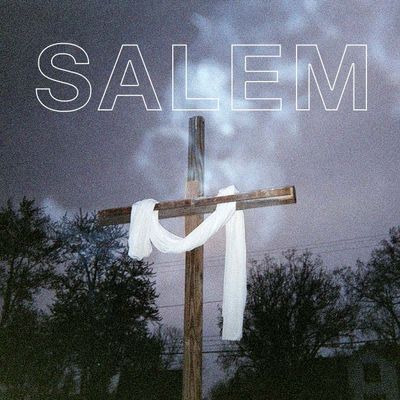

While musicians and fans were collectively struggling with how to describe music like witch house that was built on uncomfortable ideas and themes — if not lyrically, then sonically — a three-piece group from Michigan called Salem became the unwilling figureheads of the genre. Over warbly keys and ominous, claustrophobic bass tones, Salem’s earliest tracks were often gorgeous and unsettling. They all sounded like unfinished demos, or like the trio had built the skeleton of a track but forgot to finish it.

Though critical reception was initially positive, the more Salem did, the harsher the reactions got. Jack Donoghue — who provided much of the vocals for the group — made the decision to sometimes pitch his vocals down and start rapping. He was accused of trying to “sound black,” and after a bad performance at the FADER Fort during SXSW, Salem went from being widely critically acclaimed to being parodies of themselves. The internet hype cycle subsumed them and spit them out before they could even figure out what they were doing. Salem’s experience was echoed by witch house as a whole: The genre was so identifiable that artists proliferated at a rapid rate, and what sounded unique started to pretty quickly feel ridiculous.

It didn’t help that what felt like hundreds of witch house bands began popping up. A band called White Ring sounded almost exactly like Salem, and others, like oOoOO, managed to nail the oppressive darkness that Salem wielded, but couldn’t maintain much of the dynamics. Even Deftones front man Chino Moreno got involved with a side project called ††† (pronounced Crosses). You had to be careful how you typed, though, because there was also a producer named †‡†, which was somehow pronounced Rrritualzzz. The writing was on the wall: The aesthetics that helped define witch house had become more important than the actual sonics. Moreno’s project actually sounded nothing like witch house, and even Clams Casino — a rap producer who made a name for himself working with Lil B and A$AP Rocky, and later produced on Vince Staples’s excellent 2015 album Summertime ’06 — was thrown in with everyone else. It’d be easy to say that witch house lost the plot, but the reality was that there wasn’t much of a plot to begin with.

It would be remiss of me to not mention my involvement in the genre. I first blogged about Salem in 2008, and championed them for years afterward. In 2015, I covered its rise and fall for Grantland. Though witch house’s tendrils would stretch beyond its closed circle of collaborators (Donoghue was involved with Kanye West’s Yeezus), and dedicated fans still populate message boards, any cohesion or scene surrounding it is now virtually nonexistent. This is not surprising — it happens to every subgenre of music ever — but witch house was defined by the fact that it never moved beyond a work-in-progress. It was the sound of a bunch of people trying to figure something out.

By the time Salem released King Night, their lone LP, in 2010, listeners were moving on. There are unfortunate moments on the album, but years later, the highs are high. Closing track “Killer” is a guitar-centric downer anthem that pointed to where Salem could have gone next (their subsequent EP, I’m Still the Night, didn’t really expand on the promise of “Killer,” but its cover of Alice Deejay’s “Better Off Alone” never got the credit it deserved). Other songs on the album played with dynamics in interesting ways — Salem were known for making music so blown out that you had to excavate for details in dense layers of sound — but tracks like “Hound” shaped that denseness into jittery washes of noise. It sounds like all the air getting sucked out of a room.

Looking back, it’s clear that witch house happened because a new crop of artists had the entire history of recorded music at their fingertips. Everything — everything — was suddenly fair game. Any sense of linear musical history was washed away in favor of genre-less, boundary-less experimentation. Everyone was trying everything, and without the artificial restriction of genre, it was a miracle that anyone ever made anything cohesive. Though the music that was categorized as witch house was dour, the enthusiasm for experimentation was palpable and exciting.

So why did we mock it into oblivion? Why do we mock anything? Is it possible that we were ashamed to enjoy music that so directly considered sadness and darkness? Papa Roach and the rest of nu metal were defined by their acceptance and empathy for adolescent rage. Over time, the nu-metal bands slowly limped back into the critical conversation, usually after some time away, or a heel-turn toward middle-of-the-road echoes of alt-rock. It’s no longer embarrassing to say you like Deftones or a sizable portion of Korn’s back catalogue. Knowing that all musical trends come in cycles, we’re in for a witch house revival in just a few years, if not sooner. For now, I’m going to jump the gun: Witch house had some clunky moments, but the nascent genre’s ability to convey despair, hopelessness, and uncertainty at what the future will hold was dead-on. Maybe the genre just needed more time to grow, and the currently en vogue collective embrace of nihilism to thrive.