When Bruce Dickinson first joined Iron Maiden, he was still using a student train pass and unofficially living above a hair salon. He lived about 100 miles outside of London, where he’d travel to practice with the rest of the band.

About five miles down the road, he’d pass time drinking scrumpy — a hallucinogenic cider made from undesirable apples — at a pub in the village of Elmley Castle. The establishment was full of semi-conscious metalheads and had a large pentagram on the floor. About ten miles west was Bredon Hill — the storied location said to have hosted the last recorded human sacrifice. Thirty miles in the other direction was the birthplace of the notorious Aleister Crowley, the mythical occultist and walking satanic symbol.

In 1982, 23-year-old Dickinson moved to London to record the band’s first No. 1 album, The Number of the Beast. He thought he’d left behind the “paradise for lunatics” and moved on to big-city living. But during the recording of the album, winter gloom, murder, and the imagery of 666 still permeated the band’s consciousness. Dickinson, who’d just been through the wringer playing in the competing heavy-metal band Samson, was cocky when he first joined Maiden — even scoffing at the notion of an audition. But it only took 20 or 30 takes of a single lyric before famed producer Martin Birch put him in his place. “This is your whole life, summed up in two lines,” he told Dickinson, after watching him throw a tantrum in the studio.

“I thought, ‘I can sing this stuff,’” Dickinson says. “And yeah, physically, there was no question about it. But it was the emotional input of doing those lines. Nobody had ever called me on that before.”

The singer then approached the microphone and uttered the introduction to “The Number of the Beast,” one of the band’s most iconic songs to date. Dickinson later learned that Birch had used the same shtick on Ronnie James Dio and the rest of his heroes in Black Sabbath just two years earlier while recording “Heaven and Hell.” “Once that little light bulb goes on in your head,” he says. “You’ve just walked into a whole new universe.”

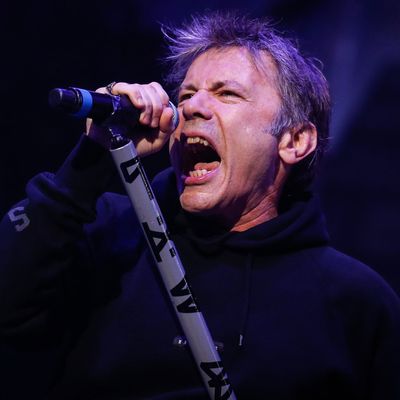

Along with countless others, this learning moment was crucial to Dickinson’s 35-year-career with Iron Maiden. Overall, the band has released 16 studio albums. They’ve played to legions of fans (upwards of 300,000 in Brazil) in more countries than most people could name. Their mascot, the demonic “Eddie,” can be seen touted by rock fans of all ages. Their statistical and economic impact on the genre of heavy metal may be outweighed only by their personal impact on fans in every corner of the world. If you ask any metal fan or critic, Iron Maiden is one of the biggest metal bands of all time. And while Dickinson, nicknamed the “Air-Raid Siren,” was not the original vocalist of Iron Maiden, he is highly regarded as one of the most dynamic vocalists in heavy-metal history — head to head with the likes of Judas Priest’s Rob Halford.

Now 59, he has lived as an airline pilot, competitive fencer, filmmaker, broadcaster, legendary front man, and solo recording artist. And with the release of What Does This Button Do?, he can add autobiographer to the list.

The nearly 400-page book is a compelling tale of a young English boy’s road from corporal punishment in boarding school to international superstardom. While it is a lesson in discipline and commitment, it’s also a compelling look at the wild days of the music industry, through the eyes of a man who has survived it all.

A recurring line in your book was, “Nothing in childhood is ever wasted.” What’s the significance there?

It doesn’t matter what experiences you have in childhood, it gets recycled somewhere down the line. All those things, they come back as demons. Or not.

As a child, you would look at a photo of your mother as a young ballerina, years before she’d give up on her dreams. Why did that image impact you so greatly?

It was really sad. I felt sorry for her. That was her big break and it was squished. I didn’t appreciate how sad it was until quite late on. When you’ve left the nest you start to realize these things.

Did spending time with someone who’d given up on their dreams contribute to your perseverance?

It was more internal. One gift my grandfather gave me was a TV. For a working-class family in England in 1958, having a TV was a big deal. People would come around and not even watch it, just look at it! I witnessed the Kennedy assassination and the Cuban missile crisis, all whilst looking at that little TV. I was under the age of 5 but I remember. That lens on the world. It opened out my world way beyond this little mining town of Worksop.

You’ve described your relationship with your parents as strained and somewhat loveless. You don’t have quite as fond memories of your father, do you?

When my dad took over, that threw up tension. As in me saying, basically, at 5 years old, “Who the fuck are you? You just turn up and start bossing me around?” That was obviously a source of conflict and anger.

“Where were you the last five years?”

Exactly. My dad was very young. I have no clue how I would’ve coped if I had been his age when I had kids, especially if I had a kid like me who threw things through windows because he was pissed off.

So, you have to cut people a bit of slack. He was very driven. He worked his ass off. He never went to college because they couldn’t afford to send him. He was always driven by scarcity and a fear of losing things. Consequently, he worked every hour that God made. He said to me once, “Whatever you do, have a go at everything.” That stuck with me, which is, What Does This Button Do? He was also big on was finishing what you started. This story is actually not in the book. I was racing go-karts and had an uncompetitive secondhand kart. Everyone else had big engines. I had a shitty engine. I felt embarrassed; “Why even turn up to these races, dad? I couldn’t possibly win.” And he said, “Just finish. If you finish every race that you start, you will win something. These guys are stupid. Their ego will get in the way. They’ll crash or spin out. Do what you can do. But don’t tell me what you can’t do.” That sounded like scarily good advice. I took that to heart.

It’s strange, it sounds like your father gave positive reinforcement. But eventually, you’d rather be caned at private school than spend any time at home.

Rebellion, you know? I used to argue with my dad a lot. He was pretty stubborn. He’d take up really extreme positions on politics. We’d back each other into a corner. We bonded up to a point but there was always a big distance in the relationship. Even though I was at boarding school having a shitty time, I thought, Well, at least I don’t have to deal with the emotional baggage.

I’m glad you mentioned the concept of ego. Early on, when you played in Samson, you’d already learned so many lessons before even joining Iron Maiden. Was that lesson in humility a good jump-start?

Everything that possibly could go wrong did go wrong. To compound it, one of the reasons was that the entire unit was permanently chemically impaired. It’s goofy, but it was kind of endearing. Then, joining Iron Maiden was stepping up. It was like going from Little League to the Mets overnight.

I saw you play at Madison Square Garden around ten years ago. You somehow managed to blow out the power at the Garden. Your temporary fix was playing soccer onstage.

[Laughs] Well, if in doubt, juggle! It happened in the U.K., a big place, Earls Court, a similar situation, the power supply actually welded itself together. So, it wasn’t just a question of a fuse blowing, this was actually lumps of three-phase wire that had just melted into each other. It took us 45 minutes, we switched the power off, we had guys with big chainsaws and pliers just rigging up an alternate power supply backstage. Forty-five minutes is a long time to juggle.

The reason I bring ego up … If you had too big a head, I’d imagine you’d storm off the stage in anger. You seem surprisingly levelheaded.

It doesn’t matter what you do, if you’re the best, you’ve still got limitations and deep down you have to know what they are. If you don’t, then you’re just a loose cannon or psychopathic lunatic. If you know what your limitations are, no matter how much bluster you put on the front, you stand the chance at being able to exceed them. You have to be straight with yourself. Sometimes that could be quite tough. When I left Maiden, I was pretty hard on myself. I said, “This whole setup is a limitation. It’s a lovely golden cage that’s comfortable and earns loads of money and I could go on recycling our identity, but I don’t want to do that. The only way I’m gonna find out what’s beyond and grow as a singer is to do something different. And the only way I’m gonna get taken seriously, is to leave.” I realized when you’re in Iron Maiden, everyone blows smoke up your ass. In the ’80s, when you’re in a big band, you have publicists and all kinds of people to protect you. As soon as you leave the bubble, everybody goes, “You know, I always just wanted to kick that guy in the nuts!” It’s open season! That’s what happened to me. It was a shock. But, at the same time, I was like, “Well, this is why you did it.” You step outside the box to find out what’s outside the box. You just have to take it on the chin and go, “Move on. This is evolution. This is Darwinism. It is survival of the fittest and if you can’t evolve into something that has a useful function, slink away and die.”

You said, “My problem was to establish where I belonged in modern rock music, if indeed I belonged in it at all.” Was that part of bursting out of the bubble?

Exactly. You basically throw yourself to the universe and say, “Okay, should I really exist as a singer? Is there anything useful I’m bringing to the world by being in a heavy-metal band other than nostalgia?” Because if that’s all it is, maybe I should just take that person and quietly strangle him and go do something more useful instead. If you want to be an artist, you’ve can’t be resting on your laurels. You’ve got to be out there doing something different. I didn’t know what to do, which is why I left. I think people assumed when I left that I had a plan. Nope. No plan. Which I think the guys in the band found really hard to understand.

In a similar vein, you mentioned that you didn’t know how Iron Maiden would sustain without falling into irrelevance. Why was that so important to you?

You can’t do that. Plowing the same furrow would maybe be the term. The audience would probably be happy with that, although it would slowly diminish. The band would become less relevant and gradually turn into a blob with the rest of the metal community. That’s not what I wanted. I learned so much when I was out of the band. I was a way better singer when I came back to Maiden than when I left. Consequently, the album we did when I came back, Brave New World, I think is one of our classic records of all time. That was because all the energy was back. Everything in the band changed at that point.

Before I’d left, there’d always been these little power struggles. When I came back, it was much more honest. People always say, “Maiden is like a family,” like a family is a good thing. But families aren’t necessarily good things. A happy family is a great thing, but families are just random events that happen. That organisms pop out of the same hole, that’s no reason why they should like each other, in truth. All this “Blood is thicker than water” … sorry guys, if your brother is an asshole, he’s an asshole!

We’re probably more friends now than we ever have been. We’re a band of brothers born out of the same mother, which is Iron Maiden. The mother ship gave birth to our relationship. We all accept that now. My loyalty is not to Steve, Adrian, or Janick. It’s to Iron Maiden and on that basis we have a great relationship. It means that we forgive each other, all of our little trespasses, if you want to use the Lord’s Prayer. I think it’s the same for everybody in the band, like, “Nu uh, it’s about Maiden, stupid.”

In your book, you detailed your experience with cancer intimately. But are you tired of talking about your tongue cancer? Or do you like putting it out there?

It doesn’t overly concern me. What I don’t want to turn into is somebody where people come up with sick babies and say, “Touch my baby! Heal me!” It’s a scary subject, particularly for people who are afraid of it or who know somebody with cancer. Obviously it was the beginning of the rest of my life. I also wanted to redress the balance from some of the really salacious shitty stuff that the trolling journalists stuck out when I first got it. There were some really offensive things. It’s not fair to every other man that might have this cancer. If you said that about women with cervical cancer, people would be outraged. But because it’s a guy, “We can make all these jokes about oral sex and put out offensive things about his wife.” It’s outrageous. Also, there’s a genuine public-health concern. This is a really big issue that’s gonna come back to bite 80 percent of the population, men and women. It’s something that people should be aware of but not scared of, because it’s a highly curable cancer. That’s why it’s in the book in that kind of detail.