For a fleeting moment, it seemed like Jeff Lemire was finally slowing down. When I sat down with him at a hotel bar during this July’s San Diego Comic-Con, I asked the famously prolific writer-artist how he found the time to create the many comics he’s worked on. “Actually, it seems like I’m doing a lot more than I am,” he said. “Last year, I was writing eight books and then drawing two of them, so that was too much. But now I’m only really writing about three books a month and drawing one, so that’s pretty manageable for me.”

However, a few minutes later, he admitted that he was about to write a new series for DC Comics, later identified as The Terrifics. A few weeks after that, another DC book was announced, Inferior Five, which would feature writing and art from him. Then came the debut of Sherlock Frankenstein and the Legion of Evil, a new spinoff mini-series from one of his existing series at Dark Horse Comics. And earlier this month, Dark Horse announced yet another new mini-series he’d be writing, Doctor Star and the Kingdom of Lost Tomorrows. As the dawn of 2018 approaches, it looks like Lemire has yet another frightfully busy year ahead of him.

He’s used to that, and his productivity has paid off. The past decade has seen a meteoric rise for Lemire. His first published work — a little-read graphic novel called Lost Dogs — only arrived in 2005. Flash forward to now, and Lemire has a bibliography whose length rivals that of creators with three times as many years in the industry as him. The size of his résumé is impressive, but so is its range. He’s written mainstream superhero work (Animal Man, Moon Knight, Old Man Logan, All-New Hawkeye, Extraordinary X-Men, and Bloodshot Reborn, among others); but he’s perhaps even better known for quirky creator-owned titles that he’s either written (Descender, Black Hammer, Plutona) or written and drawn (Sweet Tooth, Trillium, The Underwater Welder, Royal City, Roughneck).

When I pressed Lemire on the question of how he gets it all done, he admitted that it might have to do with his upbringing in semi-rural southwestern Ontario. “I grew up on a farm, so we were expected to do a lot of work there,” he said. “I think you get a pretty good work ethic. My parents have a pretty incredible work ethic, so I probably got it from them. But I’ve always been very organized. It’s just the way I think.”

Lemire didn’t sound boastful when he said those words. He never did, throughout the entire conversation, even when he was speaking about his successes. Indeed, the whole interview was devoid of emotional frills. He’s a restrained and plain-spoken man, not given to much in the way of sentiment. Case in point: We were briefly interrupted by a woman who wanted to meet Lemire, and when she went in for a hug, he politely rebuffed her. As she walked away, he looked at me from behind his thick-framed glasses and said, “I’ll give you the headline: ‘Jeff Lemire, not a big hugger.’”

The most animated he got was when he spoke about the comics that shaped his brain when he was younger. His early-’80s childhood was spent perusing the spinner racks at gas stations, where superheroes abounded. “All you could really get was Marvel and DC stuff back then,” he said. “I was always a DC kid. I just loved that universe. I just would sit around and copy drawings from those books all the time and write my own Batman stories.” In the mid-’80s, he discovered a comics shop not too far from where he lived and new horizons were opened up for him in the years when the medium was taking some great leaps forward. “That was kind of like a golden age for comics, really, where you had The Dark Knight Returns, and Watchmen, and stuff like Tim Truman’s Scout really hit me,” he said.

His obsession grew, and in the early ’90s, he thrilled at the dawn of DC’s ambitious, adult-oriented Vertigo line. “Those were the perfect books for a moody 14-year-old Jeff Lemire: Hellblazer and Sandman and all that stuff,” he said. The final building blocks of his comics imagination were laid when he moved to Toronto and discovered hip shops like the Beguiling. It was there that he stumbled upon work totally divorced from cowls and spandex. “I started to discover underground cartoonists like Chris Ware, and Dan Clowes, and European cartoonists, and guys like Paul Pope,” he said. “It just reinvigorates your love of a medium at a different point in your life. There was always those things along the way that kept me in love with comics and made me want to draw.”

But although he wanted to draw, he assumed there wasn’t much point in pursuing a future where he did that professionally. “There was no comic-book university,” as he put it. So when he looked at higher education, he opted to go to film school. “All I really knew was, I wanted to tell stories. So I thought, Maybe that’s an avenue, because there really was a booming film industry, especially in the late ’90s, early 2000s, in Canada and Toronto.” In other words, it was a safer bet than the tumultuous world of the funnybooks. “I thought, Well, y’know, it’s an actual industry, there’s schooling, I can maybe get a job afterward and work my way up,” he said. “When you’re 18, 19, you don’t really think all this stuff through.”

Film school, as it turned out, ended up being “a four-year process of deciding I didn’t want to do film, I wanted to do comics.” He fell into a series of dead-end jobs while cranking out never-to-be-published stabs at sequential art. While struggling as a nighttime line cook at a cheap Mexican restaurant in Toronto, he put pen to paper and began work on Lost Dogs, a graphic novella about a sailor who turns to prizefighting after losing his wife and daughter. Lemire wrote and drew the first 12 pages of the black-and-red-streaked tale in a single 24-hour period, and after spending a month finishing it up, he won a $5,000 grant to self-publish the book with a run of 700 copies. It may not have been a huge hit, but it was a confidence-booster and set him up for his massive next step.

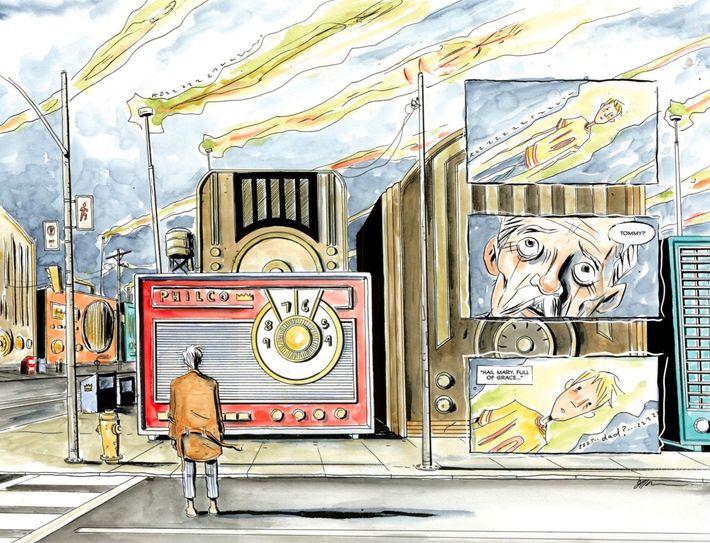

Essex County was light-years ahead of Lost Dogs in its emotional breadth and thematic depth, recounting a multigenerational saga about a family in rural Canada. He sold indie publisher Top Shelf Productions on the idea and it was published in the form of three books from 2006 to 2008. The branching, achronological narrative came out of Lemire’s changing perspectives on the people that surrounded him as a child. “I had been away from home for long enough that I could look back on my childhood,” Lemire said. “I wanted to do something really personal and that was really me. So I went back to my childhood and just told a story about where I grew up and how I grew up.” It was a sensation, snatching up award after award and being named by the CBC’s Canada Reads program as one of the best Canadian novels of the decade — something no comic had done before.

With his swirling, thick-lined visual approach and stark prose style, Lemire was in a position to become a young turk of realist indie comics at the turn of the decade. But he took a sharp left turn into genre work. He was snatched up by DC, embarking on projects for the Vertigo imprint he’d so loved as a kid. First came a hardcover graphic novel based on H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man entitled The Nobody, but while researching it, he found his mind drifting toward another Wells work: The Island of Dr. Moreau. Its human-animal hybrids, as well as those of comics legend Jack Kirby’s postapocalyptic series Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth, started dancing around in his imagination. As Lemire said, “You just put your love of all these different stories that you love into something new.”

That something new was another Vertigo title, one that would further cement his place as a formidable new talent: Sweet Tooth. Running from 2009 to 2012, it was a monthly series about a part-boy, part-deer named Gus and his grizzled human companion Jepperd, the two of whom wander a North America that’s been destroyed by a mysterious virus. By turns heartwarming and horrifying, Sweet Tooth was widely regarded as one of the best comics of the new decade, earning acclaim from mainstream figures like author Junot Díaz, and Lost and The Leftovers co-creator Damon Lindelof.

In that same stretch of time, Lemire did something unusual for a cartoonist auteur of his caliber: He started making superhero comics. DC hired him to write stories about Superboy and the Atom in 2010, but his big break in the cape world arrived when the publisher launched an ambitious, line-wide relaunch called the New 52 the following year. Fifty-two new series had to be created for it, and though many of them starred headliners like Superman and Batman, there was room for experimentation with lesser-known DC intellectual property.

“There were a few books I think DC was just kind of throwing things at the wall to see if it would stick,” Lemire said, and one such book was a revival of outré character Animal Man. Lemire was put on the project as its writer, and it became one of the most acclaimed of the New 52 series. More DC superhero-writing work followed in the pages of Frankenstein, Agent of S.H.A.D.E., Justice League Dark, Green Arrow, and Justice League United, among other titles.

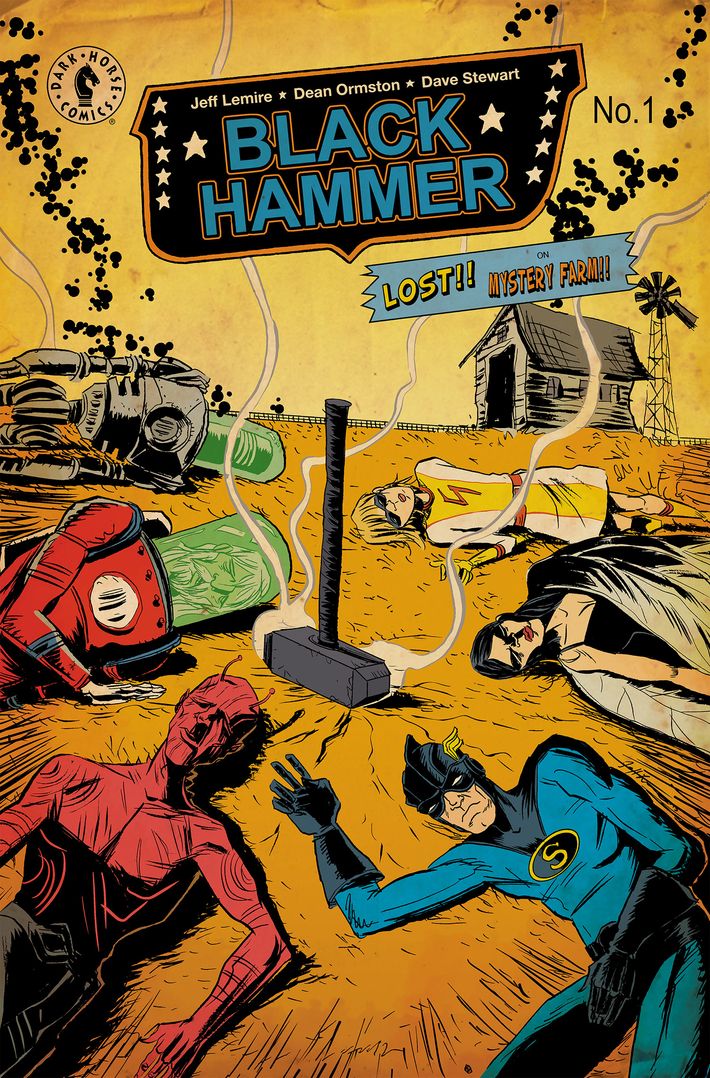

It was in those early and middle years of this decade that Lemire’s prolific nature first came into full view. In addition to all of the aforementioned superhero and Sweet Tooth material, he also wrote and drew a Top Shelf graphic novel called The Underwater Welder (which Ryan Gosling is now planning to adapt) and began writing for upstart superhero publisher Valiant. Sweet Tooth wrapped up, but he almost immediately started writing and drawing another Vertigo series, Trillium, a piece of semi-experimental art in which the reader had to repeatedly rotate the comic in order to follow the plot. In 2015, he jumped ship from DC to Marvel for multiple assignments and also started writing two creator-owned series at Image Comics, Descender (drawn by Dustin Nguyen) and Plutona (drawn by Emi Lenox). Then came Black Hammer, a dark superhero pastiche co-created with artist Dean Ormston at Dark Horse. In 2016, he worked on ten different comics in one capacity or another — something unheard of in the industry.

Even for someone with a farmer’s work ethic, it was too much. Something had to give, and it ended up being his gigs at Marvel. “Last year at this time, it was rough, and a lot of it was the Marvel stuff I got,” Lemire told me. He’d been writing All-New Hawkeye, Old Man Logan, Extraordinary X-Men, Thanos, and Moon Knight for the venerable superhero house, as well as co-writing a crossover event called IvX and its prelude, Death of X. “That kind of made me want to, yeah, scream and do terrible things,” he said. I asked him what specific problems he was having with the company, and he declined to get into specifics other than to say, “It wasn’t a great fit.”

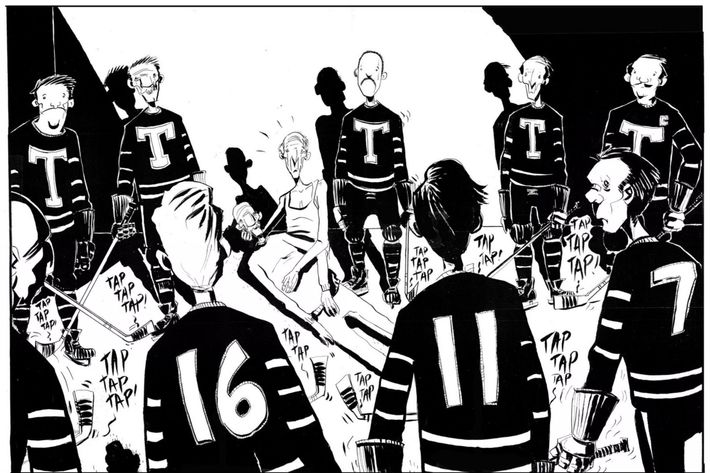

Luckily, he’d earned enough fame to be able to move to a more personal set of projects. The past few months have been ones in which Lemire has been asserting his own muse. He’s been particularly proud of Black Hammer, and has decided to use it as a foundation stone for an expanded universe: the aforementioned Sherlock Frankenstein and Doctor Star minis (drawn by David Rubín and Max Fiumara, respectively) both build on Black Hammer characters. His newest Image series, Royal City, which he writes and draws, is a tender look at a family whose members are each being individually haunted by versions of a dead relative. Perhaps most notably, Lemire put out yet another fully formed graphic novel this year, a chronicle of a bitter Canadian former hockey player called Roughneck. It was released not by a comics company, but by Simon & Schuster — and when I asked why, Lemire let slip just a little bit of bragging, however restrained. Essex County is, according to him, “a real literary kind of classic now” in Canada, and he “kind of wanted to follow that up” with “something that was specifically for the book market.”

Still, he hasn’t abandoned the kitschy roots of his childhood. He’s making his return to DC with one of the flagship titles of their “New Age of DC Heroes” initiative, The Terrifics. Drawn by Ivan Reis with character designs by Evan “Doc” Shaner, it’s a riff on Marvel’s Fantastic Four that will feature sunny, high-flying adventure when it launches in February. June will bring his collaboration with legendary writer-artist Keith Giffen — a childhood idol of Lemire’s — on Inferior Five. Described by Lemire as “sort of a DC Comics version of The Goonies, or Stranger Things, or It,” it will have art from Giffen in the main stories, but also Lemire’s debut as a recurring DC superhero artist in backup features about old-school figure the Peacemaker. It wouldn’t be shocking to hear that he’s got something else in the works that’ll be announced before too long.

This ever-expanding portfolio shows the other thing that makes Lemire remarkable, apart from the quantity of his output: his ecumenicalism. He’s the rare comics creator who can do a Royal City at the same time as an Inferior Five, and the even rarer one who can write and draw for both. “I love all comics,” he said. “I’ve never been a snob about it. I don’t turn my nose up at superheroes or genre stuff. I think good comics are good comics. I love being able to play with all that stuff.” He paused for a second and cracked an ever-so-slight smile. “As long as I can, why not, right?”