After a 26-year, industry-changing run, DC Comics has canceled its Vertigo imprint, the home of the Sandman, Preacher, Y: The Last Man, and many other enduring, adults-only hits. Sadly, the news wasn’t unexpected, as sales had been disappointing for the better part of a decade, despite numerous reboot attempts. (The most recent happened this past August.) Given this news, we’re republishing this essay from January 2018 about Vertigo’s significance, which was originally published on Vertigo’s 25th anniversary.

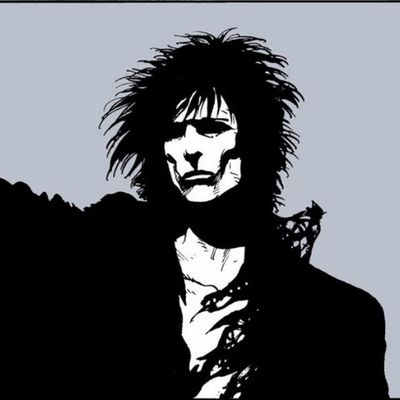

Over the past few years, I’ve repeatedly tried to find a juicy story about the founding of Vertigo, the “mature readers” imprint of DC Entertainment. I always fail, and everyone involved should take that as a compliment. By all accounts, the process behind the scenes was dull (in a good way). As the 1990s dawned, DC Comics editor Karen Berger had already built a name for herself, helming a handful of acclaimed series that walked their own weird path, diverging from the standard all-ages superhero fare that the average comics fan was familiar with. The Sandman, The Saga of the Swamp Thing, Animal Man, Doom Patrol, Hellblazer, Shade, The Changing Man — these were unprecedented experiments that birthed indelible new characters and reinvented old ones. In shepherding those books, Berger fostered the development of some of comics’ most stunning young talents, many of them British: writers like Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Peter Milligan, Jamie Delano, and Grant Morrison, to name just a handful. So one day, DC’s powers-that-were asked Berger to set up her own imprint where such creators could tell impressionistic, unsettling, explicit, and formally inventive stories. A few months later, Vertigo was launched. No uphill climb, no personality clashes, no desperate searches for funding. That was that.

In other words, perhaps Vertigo was simply an idea whose time had come, and the Weltgeist had no interest in standing in its way. In January of 1993, 25 years ago, those aforementioned six series got the Vertigo label stamped on their covers and two mini-series became the first titles to begin with said label: Enigma and the Sandman spinoff Death: The High Cost of Living. This landmark is being recognized quietly. To DC’s credit, a celebration-slash-relaunch of the imprint is planned for August, but this frozen month saw no parades for Vertigo. That’s somewhat fitting for an experiment that was remarkable for the degree to which it favored contemplation over bombast, conversation over kicking.

It’s essential to remember how unusual such an approach was back in ’93. The previous few years had seen the rise of the blockbuster superhero comic. Marvel was breaking sales records by hawking titles in which oversize forearms held oversize firearms. DC had punched Superman to death and was rewarded with fevered media coverage. Boob-and-blood-obsessed creators like Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld had turned into crossover superstars and joined with some like-minded colleagues to form a publisher called Image. Fans were being told that every issue of these kinds of comics were collector’s items, leading to a speculation bubble the likes of which the industry had never seen. It was an era in which the adolescent froth of sex and violence was quite lucrative, and countless consumers had no reason to believe the ride would ever end.

Then, here came Vertigo, walking leisurely in the opposite direction. Though its writers had great respect for pulpy tales of spandex, they’d also spent considerable time reading — horror of horrors — poetry and prose. Their artists paid homage to cape-and-cowl legends like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, to be sure; but they were just as interested in Monet and Dalí. You’d occasionally see characters with some of the trappings of the American superhero, but their adventures felt more like therapy sessions than monomyths. There was sex and violence, yes, but it usually came with consequences that weren’t paved over when the next story line began. The imprint was beloved by teenagers, but it didn’t alienate adults. And good taste won in the long run: If a comics newbie asks a veteran for a first hit, it’s approximately 8,000 times more likely that the recommendation will be Sandman rather than, say, Youngblood.

But, like so many innovators, the imprint eventually became a victim of its own success. Others — including, in a fascinating historical irony, Image — adopted the Vertigo aesthetic and have grown rich off of it. Meanwhile, despite the best efforts of some very talented people, Vertigo has gradually withered into a shadow of its former self, especially after Berger’s 2013 departure. Bound editions of old series still rake in cash at bookstores and comics shops, but recent titles have failed to make a dent. The upcoming reboot may recapture former glory, but if it’s going to do so, new editor Mark Doyle and the leadership at DC would do well to study what made Vertigo so ahead of its time.

For one thing, it rewarded its creators. It’s all too common to see comics companies place their intellectual property ahead of the people responsible for advancing it. If you create a new superhero for the Marvel universe today, for example, you retain no ownership rights over it and aren’t entitled to any money for its adaptations into other mediums. DC has a more generous profit-sharing program for new creations, but their creators still don’t outright own their brainchildren. If you build a new toy, the C-suite can nab it away from you at any time and kick you out of the building so you never touch it again. It’s an approach that disincentivizes risk-taking on the part of writers and artists. Why put out your best stuff if you don’t get to control it?

That was a problem that Vertigo was keenly aware of. It offered a much better deal: Berger enabled writers and artists who invented entirely new characters under the Vertigo banner to retain full rights to them and their stories. Not only did that tactic embolden people to think big, it’s also had downstream effects on the rest of the entertainment economy. It’s why we’re able to get wild, thrilling adaptations like AMC’s Preacher, a rendition of Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Vertigo series of the same name. They were able to shop it around and do as they liked with it, without having to worry about it being watered down by skittish Warner Bros. bigwigs — and that’s how television ended up with a series where an angel and a vampire can do cocaine together. DC still makes money from sales of the comic, but Berger and her collaborators weren’t afraid to allow great minds to run wild and retain the sweat of their brow.

Creator ownership wasn’t an entirely new concept in comics when Vertigo implemented it. Indie publishers like Eclipse and Pacific were pioneers in that field a number of years before, and in 1982, Marvel had even tried to pull it off with a creator-owned imprint called Epic. But by the time Vertigo launched, those efforts had all faltered. Vertigo succeeded because it wasn’t just a creator-owned initiative, it was a brand. Berger and her cohort were brilliant at marketing the imprint as the place where readers both young and old could find outré works that never quite resembled one another, yet shared a philosophy of ambition. You knew that the Vertigo label meant there was something interesting about what was underneath the cover. It was the best of both worlds: the financial ethics of an indie company with the selling (and hiring) power of a multinational corporation.

Key to that brand loyalty was the degree to which Vertigo reached out to a wide array of readers and, once it had them, didn’t talk down to them. Marvel and DC today are, to a large extent, beholden to the so-called “Wednesday warriors”: the people, typically imagined (whether or not market data backs this up) as straight, white males, who reliably show up every Wednesday to pick up new comic books at their local shops. When those people get up in arms about a comic, their voices are heard all too loudly by the people in charge. They’re the superhero industry’s base, the ones everyone at the top fears alienating. If they’re up in arms over a change or a story line, you can expect to see it disappear sooner rather than later. As a result, Marvel and DC’s lead characters, as of 1993, were overwhelmingly straight, white men, and long had been. A thin tranche of the population guided the creative direction of an entire industry.

Vertigo, on the other hand, was entirely uninterested in limiting its perspective like that. Its characters came from a dizzying array of ethnic backgrounds, defied gender stereotypes, and were often queer in ways that mainstream art in any medium was loath to depict at the time. Women lined up in droves, dressed as Death of the Endless, eager to get Gaiman to sign their books. A young Steve Orlando, now a superstar bisexual comics writer, found himself reading Enigma and being stunned by the non-hetero content therein. People of color abounded in tales like 100 Bullets, Cairo, and Y: The Last Man.

And beyond the diversity of the characters, there was the sheer diversity of the styles. You could find stories about cops, stories about criminals, high fantasy, low fantasy, realism, surrealism, sci-fi, political drama, and sci-fi political drama all at once. Golden-age Vertigo was willing to try odd ideas out and commit to them. If they didn’t work out, they weren’t spooked away from future innovation. What’s more, they were often willing to gamble on relatively untested creators, giving them the kind of megaphone usually reserved for tested company men. It was all a series of remarkable gambits for a spandex-fixated industry, and it paid off in the way it brought readers who couldn’t give less of a crap about Superman into the sequential-art fold.

It wouldn’t last. It’s impossible to pinpoint a single cause for Vertigo’s decline in the present decade, but it’s not hard to find a likely culprit. DC Comics took a decidedly more risk-averse turn in 2011 when it reformatted itself as DC Entertainment, an entity explicitly dedicated to making its comics properties more marketable in television, film, and video games. That can still lead to wonderful art, of course, but DC had no incentive to prioritize an imprint that rewarded creators with full control of their characters and stories in other mediums.

Berger left Vertigo in 2013, and though good books were launched under the tenure of her successor, Shelly Bond (Gilbert Hernandez and Darwyn Cooke’s The Twilight Children was terrific), they didn’t reach the old heights of fame. Bond was forced out in 2016 and the flow of Vertigo titles has slowed to a trickle, holding place until the Doyle-supervised relaunch. We don’t know what the parameters of that effort will be, and it’s entirely possible that the secret ingredient was always just Berger’s good taste, which is now being ported over to her latest effort, the Dark Horse Comics–published Berger Books line. Nearly all the indie publishers try to be like classic Vertigo these days, anyway, so maybe nu-Vertigo will just feel like a Johnny-come-lately. It more or less doesn’t matter. If the relaunch gives us great stuff, terrific; if not, the ethical, unrestrained spirit of Vertigo lives on elsewhere.