It’s not hard to see why Philip K. Dick’s stories are adapted so often. They’re imbued a frequent sense of paranoia, a fixation on memory, and a haunting discussion of identity, all of which remain every bit as timelessly fascinating now as they were during his decades-long career. At this point, Dick’s work has influenced generations of writers and directors: Blade Runner and Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly are both based on Dick’s ideas, and one can draw a line from his 1957 novel Eye in the Sky to the Black Mirror episode “USS Callister,” for instance. So it’s not surprising to see an anthology show built entirely around his short fiction: Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, which debuted late last year in the U.K., and recently premiered Stateside on Amazon Prime.

The ten stories adapted for Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams are scattered across a number of collections. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, which has published a number of Dick’s books in the United States, released a tie-in volume collecting all ten, along with short essays by the screenwriters responsible for adapting them. In some cases, this offered insights into why certain changes were made from page to screen. That said, fidelity to Dick’s original texts didn’t necessarily correspond to a level of quality: One of the most effective episodes was especially faithful to the original story, while another that impressed me had almost nothing in common with its prose counterpart. Here’s a look at what changed and what was left intact when bringing each story into a new medium.

“Real Life”

In his introduction to the story “Exhibit Piece,” on which this episode is based, Ronald D. Moore (Battlestar Galactica, Outlander) notes that his adaptation opted for a less literal approach. “Very little remains of this story in the show,” he admits.

Both story and episode focus on someone living in the future who then enters a compelling simulacrum of the past. In the case of the story, that’s George Miller, first glimpsed wearing “an archaic suit from the twentieth century” en route to his job at the History Agency. He explores the exhibit that he’s tasked with supervising, and finds himself greeted by a wife and children in Eisenhower-era America. Memories of a life in this time and place come flooding in, even as his colleagues in the present day attempt to convince him that none of it is real.

Very little of that is adapted directly in the episode. “Real Life” begins with driven Chicago cop Sarah (Anna Paquin) on the hunt for a master criminal in a futuristic landscape. Her wife, Katie (Rachelle Lefevre), offers her a virtual-reality “vacation,” which brings her back to our present, in the body of wealthy inventor George (Terrence Howard), searching for revenge on the criminal who killed his wife. George also invented a virtual-reality device, leading to an increased sense of ambiguity about whether Sarah or George is real, and whether the other is a simulation.

Where “Exhibit Piece” is relatively staid — a man trying to figure out if he’s a futuristic bureaucrat or an office worker in the past — “Real Life” introduces a central character (or central characters) whose work is more kinetic. Much like the story, as Sarah spends more time in George’s life, memories of his world begin to flood her mind. The episode’s characters are also more questioning of their circumstances, with good reason. Sarah herself wonders if her life is too good to be true: “Doesn’t it seem like some ancient male fantasy? What they used to call science fiction?”

One small detail that plays like an homage to the story: Sarah has a fondness for a retro diner. Her partner keeps referring to her fries as “fingers,” an echo of the moment in the story where George’s co-worker is bewildered by his “alligator hide briefcase.”

Of course, the casting of Paquin and Howard also opens the door to questions of race and gender that the original story never did, although neither is fully explored in the episode: Both Sarah and George are married to versions of the same woman, though in George’s world she’s been killed, and he’s looking to avenge her. The combination of casting and premise would suggest that there’s more to be said here, which the episode never quite does.

“Autofac”

After a devastating war, a surviving pocket of humanity must contend with a new threat. An automated factory has survived the war and continues to send out products, and its mining for raw materials threatens the continued existence of people with no need for the goods it provides.

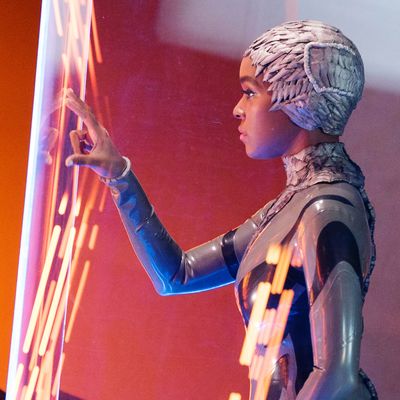

Certain aspects of this satire of consumerism have been amplified from page to screen by writer Travis Beacham (Pacific Rim), but they seem largely in keeping with Dick’s satirical jabs in the original. When Janelle Monáe shows up as an android representative from Autofac, her dialogue is delivered with a pitch-perfect faux-empathy that echoes every automated customer-service line you’ve ever called. (Here, Monáe is playing an android who toes the company line — basically, the anti–Cindi Mayweather.) And Autofac’s methods of delivery here include an abundance of drones carrying perfectly packed brown boxes. Any resemblance to the company airing Electric Dreams in the United States is, I’m sure, entirely coincidental.

Both story and episode involve a trio of people using an Autofac device to reach out to a wider corporate network. In both, the same method is used: entering the word pizzle to bewilder the automated system. There are some smaller alterations here as well: The trio that initially reaches out to Autofac is all-male in the story, while Juno Temple’s Emily is the focus here. At one point, she also salvages a collection of Jorge Luis Borges stories, which is about as overt a nod to Dick’s work as you can get without actually having someone pick up a Philip K. Dick book.

“Human Is”

Some of the Electric Dreams episodes keep the names of the characters the same and change virtually everything else. The reverse is true for “Human Is,” which alters the names of several of its characters, but leaves the story beats intact. Thanks to three terrific performances and some judicious expansion of the story’s core themes by writer Jessica Mecklenburg (Stranger Things, Gypsy), it makes for one of the highlights of the season.

The arc of the episode is the same: The protagonist’s husband returns from an interstellar mission with a radically altered personality. She begins to suspect that an alien being may be possessing him, but since this new personality is altogether friendlier and warmer than her husband had been, she’s fine with it. In the story, they’re Jill and Lester; in the episode, they’re Vera (Essie Davis) and Silas (Bryan Cranston). The episode’s third major character, General Olin (Liam Cunningham) occupies a place roughly similar to the one that Jill’s brother Frank has in the story.

Other expansions and alterations in the episode’s script accentuate the themes of the story. In one scene, Vera ventures into an underground community, seeking the attention and pleasure that the standoffish Silas is unwilling to provide. The climax, in which Vera turns the tables on the government officials who believe that Silas has been taken over by an alien, is expanded: In the story, she tells them that he’s fine and that’s that, but the episode makes room for both Davis and Cranston to have big acting moments. The story also hints that the original Lester can be recovered; that option does not seem to exist in the episode.

The impression that the story gives is of Jill and Lester as a relatively young couple; she mentions being married for five years and they have a young son. In the episode, despite having been matched by a state-run procreation program in the episode, Vera and Silas have no apparent children, perhaps an echo of the planet in decline that provides the backdrop. The fact that Vera and Silas appear to be older than their counterparts in the story also makes the pain of their marriage more deeply felt.

“Crazy Diamond”

Tony Grisoni, who adapted Dick’s story “Sales Pitch” for Electric Dreams, has adapted works by the likes of Hunter S. Thompson and David Peace for the screen. In his introduction to “Sales Pitch,” he cites a 1978 interview in which Dick expressed his regrets at his own ending for the story, first published in 1954. Grisoni refers to “freely adapting” the story, which is accurate. In both story and episode, a couple named Ed and Sally have an unexpected visitor who offers to sell them something. That’s about where the similarities end.

In the story, Ed is an intergalactic commuter who dreams of a less technological life, a potential move that his wife is less entranced by. They’re soon interrupted one night by a massive robot known as a “Fully Automatic Self-Regulating Android (Domestic),” or fasrad, which proceeds to destroy their home as it makes a sales pitch for itself.

In “Crazy Diamond,” Ed and Sally are Steve Buscemi and Julia Davis, and the unexpected visitor is Jill (Sidse Babett Knudsen), who’s selling insurance — specifically, a double-indemnity policy. As that might suggest, the episode is as influenced by film noir as it is the works of Philip K. Dick. Jill, a synthetic human, has been carrying on an affair with Ed, whose wanderlust manifests itself as a desire to travel the world on a sailboat. During a scene of Jill bonding unexpectedly with Sally, Sally recounts a strange dream she’s had, which neatly encapsulates the plot of the original story: “I even dreamt we had this fasrad come around, who wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

“The Hood Maker”

“The Hood Maker” uses numerous elements from the original short story, but dramatically repurposes them, altering where our sympathies fall and who occupies a more heroic and antagonistic position within the narrative. It also manages the neat trick of simultaneously seeming to be set 40 years in the past and 40 years in the future, which, given writer Matthew Graham’s background on shows like Life on Mars, seems appropriate.

The story itself feels very American: There’s an allusion to debate over “the Anti-Immunity Bill,” and whether it’ll actually pass. The episode, by contrast, feels very English — and the bill in question has already become law by the time the episode opens. That immunity is from being telepathically probed: In the near future of both story and episode, the government uses a group of telepaths (or “teeps”) to monitor crime. The hoods in question allow people to keep their thoughts to themselves; in his introduction to the story, Graham writes of his first encounter with the story, and believing the hoods to be actual hoods, rather than “a concealed metal headband.” In the episode, however, the hoods are proper hoods, equal parts postapocalyptic garb and Greek theatrical masks. It’s a disquieting look, but that’s in keeping with the way, in this adaptation, that what’s heroic in the story becomes sinister, and vice versa.

Consider the role of the telepaths: In the story, they’re portrayed as decidedly sinister, a group with an ominous agenda and a willingness to use their abilities to advance it. (They’re compared to Nazis and Bolsheviks at one point.) In the story, they’re the result of an explosion on Madagascar — and, at the story’s climax, they discover that they’re sterile, a piece of information that causes one of their leaders to commit suicide. In the episode, they’re more along the lines of mutants in the Marvel Universe, or the precogs in fellow Dick adaptation Minority Report: a next step in evolution who unnerve plenty of people who lack their abilities.

Dr. Cutter, the hood-maker of the title, is portrayed as a rogue but honorable scientist in the story; in the episode, Richard McCabe’s performance hits a number of mad-scientist beats. The story’s Cutter is a kind of resistance figure, while recipients of the hoods in the episode tend to use them for hate crimes. The primary telepath in the story is Ernest Abbud, who’s also the villain; Honor (Holliday Grainger), a telepath working with the police, is arguably the episode’s most sympathetic character.

“Safe and Sound”

“Safe and Sound,” which adapts the story “Foster, You’re Dead,” is one of two episodes this season that takes substantial liberties while remaining thematically consistent with its source material. Collaborators Kalen Egan and Travis Sentell have both worked with Dick’s estate, and this adaptation echoes the spirit, rather than the letter, of the original work.

“Foster, You’re Dead” follows a young man named Mike Foster, who spends his school days preparing for nuclear war. Foster is shunned because of his father’s “anti-P” stance: The family doesn’t have a fallout shelter, as Foster’s father feels that they’re a consumerist ploy to convince the population to continue buying things. The story more or less bears this out, showing how newer and fancier shelters are trotted out regularly by their vendors. By the end of the story, nuclear anxiety has been supplanted by fear of “the new Soviet bore-pellets,” which in turn require the owners of existing shelters to buy upgrades in order to stay safe.

“Safe and Sound” keeps that coupling of a satire of consumerism with widespread societal anxiety in place. Its protagonist, Foster Lee (Annalise Basso) has moved with her mother Irene (Maura Tierney) from an isolated “bubble community” to a large city. Foster is an outcast here, too: Her lack of a digital tracking bracelet called a Dex keeps her as an outcast. (“Nobody knows where she’s been,” one of her classmates says.) While both of Mike’s parents are present in the short story, Foster’s father is long dead, which becomes a plot point late in the episode.

In “Safe and Sound,” nuclear anxiety is replaced with another set of grave concerns: mass shootings and terrorist attacks. But here, too, consumerism is portrayed as exploiting human fears to sell products. Specifically, Irene’s political outspokenness causes Foster to be targeted by Ethan (Connor Paolo) and his supervisor (Martin Donovan), who embroil her in a conspiracy to ultimately entrap her mother as a would-be terrorist. The endings are very different, but their critiques strike the same target.

“The Father Thing”

One of the more straightforward episodes in Electric Dreams, “The Father Thing” finds a young boy convinced that his father has been replaced by an alien doppelgänger. The episode, written by Michael Dinner (Sneaky Pete), is a largely faithful retelling of Dick’s story of the same name: The boy, Charlie, finds evidence that something’s happened to his father, he enlists some friends to help, and they stop an alien invasion. (The invasion in the story is presented as fairly localized, whereas the episode’s protagonist links up with other people online who have also noticed loved ones behaving strangely.)

Expansions fill in the backstory of the family before catastrophe struck. We meet Charlie’s father (Greg Kinnear), who bonds with Charlie (Jack Gore) over baseball and camping; we also learn of trouble in his marriage to Charlie’s mother (Mireille Enos). The story opens with Charlie having just seen his father talking to his double in the garage; the episode begins before that, with idyllic scenes of Charlie’s childhood and — after a meteor shower and strange sounds in the neighborhood — a gradual sense that something’s wrong, even before Charlie’s father’s double devours him.

However, there’s a greater sense of wrongness from the father’s duplicate in the story. Because Charles is the central character, the reader gets a sense of the father thing as a kind of flawed double. In the episode, a lump occasionally moves under Evil Kinnear’s skin; that’s about it.

“The Impossible Planet”

In his introduction to the story in the anthology, David Farr (The Night Manager, Hanna) writes, “When I adapted it I added a strangely romantic element that isn’t really in the adaptation but just leapt out at me.” Romantic isn’t usually a word that comes to mind describing Dick’s works, so for an episode that faithfully adapts a number of elements, it still lands in a different place than its source.

The setting is far in the future, to a point where Earth is a distant memory for most. (Even someone who remembers it refers to “Carolina” rather than either one of the Carolinas.) The crew of a leisure vessel, Andrews (Benedict Wong) and Norton (Jack Reynor), is hired by Mrs. Gordon — Irma (Geraldine Chaplin) in the episode — an old woman in ill health traveling with a robotic assistant (Malik Ibheis and Christopher Staines), to take her to Earth. The amount of money she offers them is absurdly large, and they set off on their voyage.

The rapport between the more pragmatic Andrews and the more idealistic Norton is taken directly from the story, as is Irma’s assistant’s dedication to her. There’s an ambiguity about Irma in both the episode and the story: Does she know that she’s being conned? Or is the illusion all that matters? In both the episode and the story, it’s explained that she has very little time left to live. Perhaps it’s enough that someone tried very hard to make her believe that she was returning to her family’s ancestral home.

Norton’s role is expanded somewhat from the story: In the episode, he’s given an unhappy relationship and an uncertainty at his chosen career, neither of which is present in the source material. The most jarring changes involve the bond between Irma and Norton, however. We learn that Norton is the spitting image of Irma’s grandfather, and he finds himself strangely drawn to her. When they arrive at their destination in the episode, it’s a harsh wasteland; the two ultimately remove their protective suits and vanish into an idyllic landscape of the past, the afterlife, or something weirder.

The story’s ending is more in keeping with what’s come before: Mrs. Gordon sees the ocean one last time, then dies and is carried by her attendant into the water. Andrews and Norton quarrel about the ethics of what they’ve done, and then Andrews finds the remain of a coin — which turns out to be a very worn piece of American currency. In this case, it was Earth all along, whereas the episode makes a pretty convincing case otherwise.

“The Commuter”

As with “The Impossible Planet,” “The Commuter,” adapted by Jack Thorne (The Last Panthers), interprets its source faithfully, but adds a more overtly metaphysical aspect into the mix. Both story and episode concern themselves with Macon Heights, a mysterious town that shouldn’t exist.

The story and the episode begin with railway-ticket-office workers Jacobson (Timothy Spall) and Paine (Rudi Dharmalingam) dealing with an exasperated commuter seeking a ticket for a destination that doesn’t exist, and then vanishing when the town’s nonexistence is pointed out. In the episode, the person making an inquiry is Linda (Tuppence Middleton), who has a prominent role in the running of Macon Heights. The story opens with a focus on Jacobson, but rapidly shifts to Paine, who enlists his wife in uncovering the mysterious history of Macon Heights, a town whose name seems familiar, but which exists on no maps.

In the episode, Jacobson is the undisputed center of the narrative. (The trip that he makes via train to seek out the location of Macon Heights is undertaken by Paine in the story.) Jacobson’s home life is also expanded in the episode: He’s married, with a teenage son who has a number of behavioral and mental-health issues. (There’s something disquieting about the racial subtext of this as well. Specifically, the choice bits from both characters in the story have uniformly gone to the older white guy in the cast.)

In both episode and story, Macon Heights is a town that would have been built had things gone slightly differently. In the story, a proposal to build it is voted down by a narrow margin; in the episode, financial issues doom it, as well as its builder. The story suggests that the time stream is fluid, and that Macon Heights’ arrival is taking place in concert with other alterations to recent history. It ends with Paine arriving home, only to learn that time has changed and he has a child who previously hadn’t existed. Macon Heights occupies a more metaphysical place here, with the changes to the time stream as a means for some to avoid trauma (one person Jacobson meets was the victim of a hate crime; another was sexually assaulted), and for others to avoid having committed violent acts that they later regretted.

A few scenes are taken nearly verbatim from page to screen, including the first glimpse of Macon Heights, as a group of commuters leap from a train and move toward “the bank of grey haze.” But a story about the malleability of time becomes an episode about the more tried and true motif of needing to embrace the good and the bad of life.

To an extent, the shifting purpose of Macon Heights adds a few moments where the plot folds in on itself. Jacobson’s initial trip erases his son from existence, while a similar lack of that caution prompts his co-worker, Paine, to have fathered multiple children in the revised timeline. It’s an interesting reversal of the story, in which the previously childless Paine discovers the existence of Macon Heights and returns home to a previously nonexistent child. But the episode’s climax, where Jacobson asks for his son to be restored to the timeline, stumbles somewhat. Wouldn’t that cause Paine’s kids to cease to exist? It’s an ethical conundrum atop another ethical conundrum, without the time given to properly process them all.

“Kill All Others”

Dick’s story “The Hanging Stranger” is about as close to cosmic horror as you’re likely to get from him. The premise is chilling: TV salesman Ed Loyce discovers a stranger’s body hanging in the local town square, and is unnerved to discover that none of his fellow citizens are terribly alarmed by it. There’s a good reason for that: Many of them, including one of his children, have been replaced by insectlike beings from another dimension. Loyce flees to another town and notifies the local authorities, only to learn that they’ve also been replaced. It turns out that the bodies act as a kind of bait, as only someone not under the control of the invaders would be alarmed by them. And since Loyce is a stranger in this new town, well …

Virtually none of that is in the adaptation by Dee Rees (Mudbound), and yet this episode perfectly captures the sense of paranoia, danger, and alienation found in Dick’s story. Protagonist Philbert Noyce (Mel Rodriguez) lives in a future society in which a single candidate (Vera Farmiga) is running for presidency of a combined “meganation” known as “Mexuscan.” The candidate makes periodic utterances to “kill all others,” and Philbert seems to be the only one alarmed by any of this. As the episode escalates, Philbert and his wife see a random person pursued by their suddenly murderous neighbors. He and his co-workers debate what makes someone an “other.” Finally, when a billboard pops up near his workplace, featuring a hanging body, Philbert climbs it in a futile attempt at protest; in the episode’s final moments, his own body hangs beside the billboard, a horrifying image in its own right and a powerful echo of the original work. The candidate declares that the “others” she referred to were those alarmed by the message of “kill all others” — a callback to the notion of the hanging bodies in the story being bait.

In her notes on the story, Rees writes about the process of adapting it for the screen during the 2016 election. There are nods to current events throughout, from the normalization of the previously unthinkable to Farmiga’s swooping haircut. But what’s most fascinating about this adaptation is how it repurposes the subtext of Dick’s story. At one point, Loyce alludes to the KKK and Nazis; in other words, right-wing terrorism and violence were clearly on his mind as Dick wrote this. But in that story, there’s at least the nominal idea that its villains are monsters from another world. In Rees’s adaptation, there’s no scene wherein Farmiga pulls away a human face to reveal something alien. In this one, the monsters were us all along.