An old teacher of mine had a portrait of Stalin hanging in his kitchen. A friend of mine used to have a large image of Donald Rumsfeld’s forehead and eyes hanging in his office. In this somewhat sophomoric spirit — not quite the full-on irony of, say, Soviet artists Komar and Melamid, whose 1982 painting Yalta Conference put Stalin next to E.T. and Hitler in the background shushing the viewer — I recently began decorating part of a wall in my apartment with photographs of minor dictators. (Most of my decorations are historical maps.) So far I’ve hung a shot of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu of Romania waving from a White House balcony in 1973 and one of Enver Hoxha addressing the Albanian Trade Union in 1954. Hoxha ruled Albania from the end of World War II until his death in 1985.

Hoxha never made much impact on American consciousness. The only time I recall him coming up in U.S. pop culture is when his voice is heard on a propaganda recording used by robbers as a decoy to distract police in Spike Lee’s Inside Man. After an education in France and a wartime career as a partisan rebel, Hoxha took power and aligned Albania with Stalin. He remained Stalinist after the Soviet leader’s death, but broke with the Soviet Union in 1962, aligning first with China and then leading the country on its own from mid-1970s, an isolate totalitarian state on a small scale. He had a bunker mentality and filled Albania with more than 170,000 bunkers to be used in case of foreign invasion or nuclear attack. State murder, political imprisonment, and internal exile were common practices under Hoxha. It was basically impossible to survive as a dissident, and being a writer meant complicity, to some extent, with the regime.

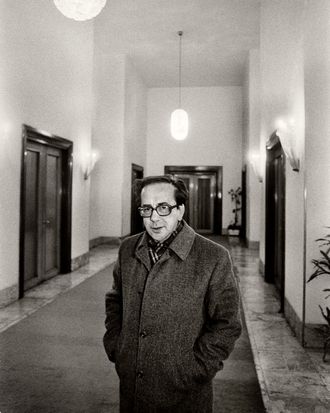

Ismail Kadare began publishing poetry and fiction in Albania as a teenager in the 1950s; became internationally famous for his novel The General of the Dead Army when it appeared in French in the early 1970s; and has for decades been seen as the first Albanian author with a chance to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, a possibility that recedes each year no matter how many £20 bets I place on him with the London bookie Ladbroke’s, which I do out of a sense of both literary appreciation and ethnic loyalty.

My paternal grandmother, Clathie, was Albanian; her parents immigrated to Boston from Korce, south of Gjirokastër, where both Hoxha and Kadare were born, in the first decade of the 20th century. My Albanian-American experience is confined to annual outings to a cookout when I was a child; obsessive following of the NATO intervention in Kosovo while I was in college; and attendance of a big party on the 100th anniversary of the Albanian Orthodox Church of Boston featuring a speech by the deputy prime minister and a set of Blues Brothers numbers performed by Jim Belushi, the most famous, after his dead brother, of all Albanian-Americans. I’ve never visited the country. The one time I tried to take a bus from Athens in 1997, after the violence around the pyramid schemes that had plunged the nation into turmoil, it was sold out. (A friend of mine tells me it’s a great place to spot rare birds.)

All along I read Kadare novels. He was the only Albanian writer you could get a hold of in English, other than a few unnoteworthy anthologies. These days Albanians are making inroads in international pop charts and winning prizes at art fairs. The prime minister, Edi Rama, is an artist himself. But there hasn’t been another literary breakthrough. Some of Kadare’s critics blame him for sucking up all the oxygen. We await the Knausgaard and the Ferrante of the Albanians.

From the start of his career, Kadare broke with the prescribed literary mode of socialist realism to write fiction rooted in history, myth, and allegory. But he never became a full-on dissident.

Doing so probably would have meant execution. (Consider the plight of those in Kadare’s situation the next time you hear American leftist activists likened to totalitarians: The comparison is ludicrous.) He saw his books banned and experienced internal exile, but he also served as a minister of parliament. A lack of purity in opposition to Hoxha may be one reason Stockholm has never honored Kadare. He describes his own relationship to the dictator as a game of “cat and mouse”: He wanted to survive, remain in his homeland, and continue writing; Hoxha “didn’t want to be seen as an enemy of writers.” Kadare left Albania on the verge of its opening up to the West in 1990 and moved to France, and since then his writing has been openly critical of the Hoxha era and its atrocities.

There are two new books by Kadare being published in America this winter — the novel Girl in Exile: Requiem for Linda B. and the collection Essays on World Literature — and another novel, The Traitor’s Niche, will appear this summer. Though more than 20 of his books are now available in English, they come to us out of sequence. For many years, so slim was the Anglophone-Albanian slipstream, Kadare lacked an English translator, and the books were translated to English from their French translations. The previous novel to appear in America, Twilight of the Eastern Gods, dates from the late 1970s and draws on his experience in 1958 as a young writer at the Gorky Institute in Moscow: The narrator, an authorial alter ego who dreams of writing the books Kadare would later write, has a doomed love affair, rejects social realism, worries that all the writers around him from various corners of the Eastern bloc might be informers, and follows the controversy in the press surrounding the award of the Nobel Prize to Boris Pasternak. It struck me as classic Kadare in a minor key, a personal book — you could call it paranoid auto-fiction — about a young writer’s collision with history. It belongs with his major works: The General of the Dead Army, about an Italian officer who comes to collect the corpses of the invaders from the Second World War; The Three-Arched Bridge, an allegory about tyranny (could be capitalist or communist) set during the Ottoman conquest of Albania; and Broken April, a tale of blood feuds in the mountains of northern Albania.

A Girl in Exile was published in Albanian in 2009, when Kadare was 73, and is thus a work from Kadare’s frankly anti-Hoxha late phase. It’s set in the early 1980s, sometime between the Iran hostage crisis and Hoxha’s death. The structure is loose, admitting dream sequences, hearsay, fragments of unfinished plays, and digressions into ghost stories. Its governing myth is that of Orpheus and Eurydice, perhaps the ultimate ghost story. The novel’s hero is a playwright named Rudian who’s come to the attention of the Party Committee and its investigator because a girl in possession of a signed copy of one of his books has died under mysterious circumstances in the hinterlands outside the capital. The girl, the Linda B. of the subtitle, is a friend of Migena, a woman engaged in an affair with Rudian. The fate of his new play is in the balance, and he wonders if Migena, whose name is an anagram for “enigma,” might be a spy for the secret police. He accuses her and has the impulse to hit her, an outburst that fills him with guilt and only further clouds his mind. What begins like a conventional thriller devolves into a muddled ghost story about the way the persecution of the few can infect a whole society. There are engaging riffs on Orpheus, flashbacks to the partisan struggle, a cameo by Hoxha himself, and a subplot about aluminum exports, but the novel never gains the tragic force of Kadare’s major works.

Essays on World Literature — consisting of studies of Aeschylus, Dante, and Shakespeare — is the more fascinating because of the way Kadare looks at his subjects through the lens of his native land. Having been a backwater for so many centuries, Kadare asserts, Albania is closer to the world of Aeschylus and to the origins of tragedy than any other modern nation. He sees the structure of Greek tragedy preserved in Albanian wedding and funeral rites and in the Kanun that, though outlawed, still governs blood feuds in the country’s mountains. Dante came late to Albania and was only read widely after the end of the Ottoman occupation, soon followed by an Italian one in 1939, and collaboration with the Italians resulted in exile for one of Dante’s Albanian translators and commentators, Ernest Koliqi, a writer Kadare compares to Ezra Pound, though he asserts that unlike Pound, Koliqi was never fascist in his literary work. He writes of a staging of Hamlet in Kosovo’s capital Pristina in 1999, after the NATO intervention, and how it was seen in Serbia as an act of revenge. Kadare’s case that his homeland is intimate with the wellsprings of the great works of Western literature is convincing. It will be interesting to see what his inheritors make of their country’s belated encounter with the present.