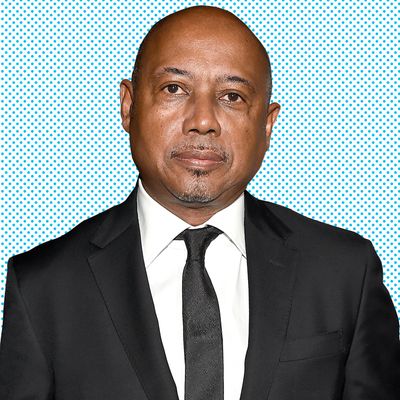

America might finally be ready for filmmaker Raoul Peck. His James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro was a surprise hit, earning an Academy Award nomination and turning the Haitian anti-capitalist into a marketable name after over 30 years in the business. Now he’s looking to make the most of it: Peck’s latest is a comic-book movie for commie millennials, an earnest and unapologetic story about some cool 20-somethings picking fights, having fun, and trying to change the world.

In European period costumes and traditional biopic formula, The Young Karl Marx is Peck’s most conventional feature so far. And yet, it’s the one he never thought he could make happen. Co-written with frequent collaborator Pascal Bonitzer, Young Marx stretches from the beginning of Karl’s (August Diehl) partnership with Friedrich Engels (Stefan Konarske), to the triumphant collective writing of The Communist Manifesto.

Ahead of the U.S. release of Young Marx, Vulture sat down with Peck to talk about the contemporary importance of Marx’s method, the role of the artist in the age of planetary capitalism, and his forthcoming projects on rebel icons John Brown and Frantz Fanon.

Who was this movie for? As a Marxist, a Jew, and a freelance writer, I felt like the movie was made for me personally.

The idea was to make a film for today’s young people. When I was your age, I remember, thank God, I had people giving me books. There were groups I could engage with, groups at the university, with friends. And this is mostly missing today. It seems like you have access to everything, it seems like you’re being informed. You know the newest Kelly Clarkson song, and you know it immediately. But that doesn’t leave space for anything else.

How did that happen?

I remember quite well when the Berlin Wall went down, I was in Berlin at the time. It was like “Okay, capitalism won, there is no more resistance, there is no reason to fight for a better world.” All of those countries became totally capitalist, even China in the way its economy functions. Profit now determines every decision. Capitalism has become a planetary system, just as Marx predicted in the Manifesto.

How useful do you think Marx’s work, and the ideas you depict in the film, are today?

Marx wrote not only as an economist, but also as a philosopher, also as a sociologist, also as a scientist. The work he left us is exactly the instrument we need to analyze what happens in this society today. He tells you how your place in the system influences your consciousness, your political consciousness, your subconsciousness. Maybe Trump says something about draining the swamp, but objectively he is part of it. Each individual reflects his place in the machine; if you don’t understand that, it’s very hard to understand what’s going on. All the bases for that analysis are in Marx.

In the movie, you do a great job placing Marx in this “Young Hegelian” milieu, which must have been difficult. So much of his early work is detailed, even petty criticism of men who are minor figures in the history of philosophy, like Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner, etc.

Pages and pages of it!

How did you go about representing that on film in an engaging way?

Marx had to go all the way to the ground on everything. He didn’t just pretend. Today, you know, with all this fake news, you just pretend, you don’t have to prove anything. Marx was exactly the contrary. When he said something he had to prove it, even if it took three months in the British Library.

If I had tried to do this movie by reading and studying all the contributors to and interpreters of Marx, I would have been lost. So we chose to go directly to Marx as a human being, as a young man in a world of inequality. If you read the correspondence between Karl and Jenny, Marx and Engels, these are young people writing to each other. In those letters there are political discussions, there’s theory. But they speak about their friends, their lives, their work. They are funny, they’re ironic, they’re passionate. That was the fuel for the film. We wrote 80 percent of the screenplay based on the correspondence, that’s why they’re so human.

There are times when the dynamic between Karl, Friedrich, and Jenny made me think of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Yes! They were in the street doing nonsense.

Jenny Marx (Vicky Krieps, of Phantom Thread fame) is a major character, she’s always one step ahead, pushing Karl and Friedrich to go further.

She was an incredible woman. Jenny was four years older than Karl, and they’d been in love with each other since their teens.

Theirs was a true love story, and she had a huge influence on his thought. It was important for us to have this strong woman character. We tend to see this big man in front and forget about the teamwork.

What do you make of the criticism directed at the film that the biopic genre or format is intrinsically bourgeois?

That’s the most crazy criticism. That’s an excuse for not engaging with the content of the movie. Film critics sometimes, you know, can be very lazy.

Come on, formal criticism is valuable too.

But I’m amazed when this is the thing they put in front of the discourse. My situation is that I’m dealing with a highly explosive subject, a taboo subject that nobody wants to deal with.

Karl Marx?

Yes, this is the first film ever in the Western world about Marx. And I managed to make an almost mainstream film out of it. You want me at the same time to play the artist and do a risky film about the way my camera moves and the way I edit? No, it’s complicated enough!

The artistic challenge — and it took me ten years with Pascal to write this story — was the writing. That was the most difficult part. We were making a film about the evolution of an idea, which is impossible. To be able to have political discourse in a scene, and you can follow it, and it’s not simplified, and it’s historically true. This is the accomplishment. So when someone criticizes the formal aspects without seeing that first, for me, it’s laziness or ignorance. There’s an incapacity to deal with what’s on the table. I make political films about today, I’m not making a biopic to make a biopic. I don’t believe in being an artist just to be an artist. And by the way, this film cost $9 million. I dare anyone in the United States to make this film for $9 million.

I heard a rumor your next movie will be about John Brown…

We have projects with Amazon and John Brown is one of them. That’s the same thing. The acceleration we’ve had over the past 30 to 40 years is a machine, you can’t stop it. There is no short-term response to what is happening in the world, to capitalism. The whole system has evolved in such a way where you can’t say as an individual “I want to stop it.” No, you lose your job. As a filmmaker, as an artist, the only thing I can do — unless we have a collective movement — is to provide the instruments for the battles to come. And that’s what I try to do with my work: Put more knowledge on the table, put more instruments on the table. And the next generation will do whatever it decides to do, but at least I make the transition, I give back what I used for my mental, political, philosophical construction.

So Marx, Baldwin, John Brown…

I had Baldwin on my list 30 years ago. Marx, I could not have Marx on my list because I never thought someone would finance a film like this. But we found a connection and we went for it. And I just finished a screenplay with Pascal on [revolutionary psychiatrist and writer] Frantz Fanon. You know Fanon?

You’re going to do John Brown and Fanon?

Of course, of course. That’s the idea! I’m not in the movie business to make films. Otherwise I could be very happy doing Scary Movie 6 and 7. It’s about how do we provide instruments and material for the next generation. Whether they use it or not, it’s going to be there, it’s going to exist. The Young Karl Marx that’s, again, the first film ever in the Western world about Karl Marx. So you can say I don’t like it or I don’t want to see it, but it exists.

For those who want to see it, they can see it. And I see the result. In Germany, in France, young people were the people who got the film right. They understood what it meant because it reflects on their life today as young people in a world of injustice. And it gives them the idea: We can fight, we can organize, we can study. It’s about learning, and working, and trying to come up with something.