2018 is a few months from over, and the year has seen plenty of films worthy of great praise — and breaking box-office history. Here are the best movies Vulture has reviewed, according to our movie critics David Edelstein and Emily Yoshida.

(A quick note about our methodology: We’ve restricted this list only to films that have had an official release in the first 10 months of 2018, though we will continue to update it throughout the year.)

Annihilation

To dismiss Garland’s trippy expedition as woo-woo nonsense would be missing out on so much emotional work that he and Natalie Portman are doing. In his hands, the annihilation of the film’s title is first and foremost psychological, and it casts a bone-deep dread over the film, even when the Hollywood narrative trappings let it down. The film departs significantly from VanderMeer’s great book, but it, too, is about something that can’t be uttered. Accordingly, Garland goes silent for the film’s stunning finale, which is something at the intersection of 2001: A Space Odyssey and modern dance, and left me breathless. —Emily Yoshida

Black Panther

A momentous event in pop culture: A comic-book superhero epic directed by a black man, Ryan Coogler, with a nearly all-black cast that set box-office records. Though the fictional African nation of Wakanda looks to the world like one of Trump’s “shitholes,” its hidden capital is a work of genius, with roots in ancient folklore, pop sci-fi, and an Afro-futurism that’s all its own. And its mightiest warriors are women. The conflict is both fantastic and real, between a king (Chadwick Boseman) trying gently to end his country’s isolationism and a separatist (Michael B. Jordan) who wants a full-scale race war. He’s crazy. But as a street kid with a chip on his shoulder, he’s compelling in ways that leave other comic-book antagonists in the dust. —David Edelstein

Blockers

Pitch Perfect writer Kay Cannon’s directorial debut is a pushy teen sex comedy with a freewheeling, improvisatory spirit that works like gangbusters. The protagonists are also the antagonists: three parents (played by Leslie Mann, John Cena, and Ike Barinholtz) on a hysterical odyssey to keep their high-school daughters from fulfilling a pact to lose their virginity on prom night. The movie has the quality of an ancient, bacchanalian comedy in which humans are reckless fools, but the forgiving spirit of comedy itself leaves the characters in one piece — and the audience exhausted from laughing. —DE

Can You Ever Forgive Me?

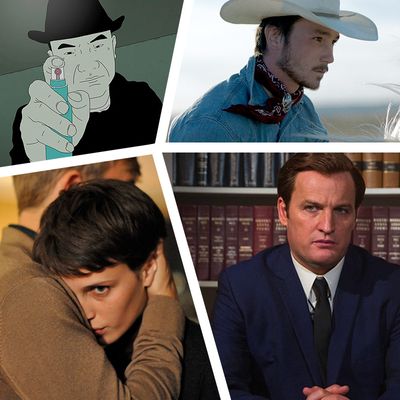

A melancholy, well-observed comedy-tinged drama from Nicole Holofcener is always something to welcome, if not be terribly surprised about. But her and Jeff Whitty’s adaptation of celebrity biographer Lee Israel’s memoir of literary failure and forgery has a deceptively wide-screen sense of loneliness, thanks to Marielle Heller’s wise, observant direction and prickly, deeply sad performances from Melissa McCarthy and Richard E. Grant. What could have been a Breaking Bad-esque ticking-clock tale of small-time crime becomes something more observant about the solitude of a life of writing about other people. —EY

Chappaquiddick

Chappaquiddick is the kind of movie that could never be made while its subject was alive, which of course is the only reason it was worth making. But rather than simply point out that the famous man did a bad thing, Jason Clarke’s fascinating portrayal of Ted Kennedy is something more elemental, a snapshot of the failure of all the things masculinity was and to some degree is still billed as. —EY

Double Lover

Like a steamy alternate-universe Frasier fanfic, Francois Ozon’s story of a woman caught between two psychologist brothers is a pulpy, uproarious stunt of a film. The twin-based body-horror premise (based on a Joyce Carol Oates novel!) is Freudian to the point of being purposefully reductive, but its sense of eroticism is far more adventurous. Parasitic twins, pegging, Jérémie Renier making out with himself — somehow it all coheres pretty seamlessly, even at its most ridiculous. —EY

Eighth Grade

Bo Burnham’s terrific debut feature reminds you what great teenage coming-of-age stories share: unbearable levels of anxiety. The movie chronicles the last week of middle school for a lonely 13-year-old girl named Kayla (Elsie Fisher), when not a huge amount happens and everything that does feels momentous. Fisher gives the impression of a girl who has been thrown into the middle of a movie without a script and forced to improvise in every scene, clinging to words like “like” and “yeah” and “awesome” while tremulously attempting to keep her head above the surface. She’s, like, awesome. Yeah. Burnham gives her a banner line, the existential question of her age, as well as an age in which kids make YouTube videos and pray for views: “It’s about ‘putting yourself out there’ — but where is ‘there’?” —DE

En el Séptimo Día

Jim McKay’s gentle but overwhelming film charts eight days in the life of José, an undocumented Mexican immigrant and food-delivery guy who sleeps in a Sunset Park, Brooklyn apartment alongside nine other undocumented Mexicans. There’s a suspenseful, go-for-it storyline — José needs to convince his boss to let him play in a championship fútbol match on a Sunday that he’s ordered to work. But given José’s essential alienation and the lack of a social safety net, the film teeters on the edge of despair. McKay leaves those of us with vastly more power feeling angry at ourselves for living comfortably within this system, for lacking not so much empathy as curiosity. It’s a social-realist triumph. —DE

First Man

Damien Chazelle’s Neil Armstrong film opens with rattles, shakes, and jerky close-ups of Ryan Gosling’s eyes as he watches primitive-looking dials with numbers going up when they’re supposed to go down. The sequence sets the tone. As in his other films, Chazelle’s protagonist is a person who sacrifices earthly relationships to reach the stratosphere, and Gosling’s baby blues seem smaller here, maybe because he turns them inward, towards more calculations, more vectors. But his impassivity is volatile — we pick up the inner tremors. As Armstrong’s wife, Janet, Claire Foy suggests fear and anger through the tension in her muscles: It’s exhausting watching her watch him. Chazelle’s La La Land felt light on its feet, effortless. First Man is purposefully laborious. The moon was hard earned and so was this stupendous movie. See it in IMAX for the first panorama of the lunar surface: The silence is exultant. —DE

First Reformed

Paul Schrader’s searching loss-of-faith drama is a late triumph in his long and bravely self-lacerating career. Ethan Hawke plays his protagonist, Toller, an emotionally bereft, alcoholic pastor in a historic upstate New York church who preaches to his tiny flock while struggling to keep his spirit aloft. The set-up owes much to Ingmar Bergman’s severely depressing Winter Light (1963), but Schrader is more attuned to specific, imminent catastrophe: This is Winter Light for the age of climate change and Trump and a sense that the church has forsaken progressive political activism opposed by big industrialist donors. As in all of Schrader’s work, the hunger for transcendence manifests itself in violence against both others and the self — though by the time he’s through there isn’t much of a separation. The question Schrader poses remains unanswered: “Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to this world?” —DE

Foxtrot

Samuel Maoz’s acclaimed and reviled Israeli triptych centers on the death, rebirth, and death of a soldier and his parent’s attempt to make sense of the senseless. It’s thick with grief, confusion, and metaphor, the latter extending to the title, the name of an isolated desert checkpoint on a road trafficked by Palestinians and a dance step in which you end up where you start. This is life, Maoz says, in a traumatized, blindly militaristic state. Its surprise failure to win an Oscar nomination is a testament to how corrosive it is and, as such, a badge of honor. —DE

Have a Nice Day

A bag of money and a botched plastic surgery create havoc in a rainy, anonymous postindustrial Chinese town in this electrifying animated crime yarn. American filmmakers looking for new depths for the neo-noir in 2018 would do well to check out director Liu Jian’s brand of brilliantly funny, utterly disaffected cynicism, and his portrayal of a world where literally everyone is just trying to make — or scam or steal — a yuan. The bone-dry humor of Jian’s Coen-esque caper is often as jarring as its minimalist animation style, but the sum of its tangled cast of characters and crisscrossing murder plots — which somehow comes in at a brisk 75 minutes — is satisfying in the extreme. —EY

Isle of Dogs

Wes Anderson’s stop-motion animated film is a gorgeous hodgepodge, its disparate elements magically unified by the director’s trademark off-symmetrical compositions, pop-out colors, and dry wit. The story of canine refugees on a garbage dump off the coast of a Japanese city is an allegorical painterly kabuki comedy that’s also a howl of rage against authoritarianism in all its forms. Voicing the main canine, a stray who says we’re all in some sense astray, Bryan Cranston gives a sharp but indelibly soulful performance. (The cries of “cultural appropriation” shouldn’t be fully discounted — only partially. Anderson’s borrowings are loving.) —DE

Leave No Trace

The extraordinary saga of a 13-year-old girl (Thomasin Harcourt McKenzie) who lives in the woods, hiding from authorities with her traumatized Iraq vet father (Ben Foster), is both melancholy and brimming with hope. They have an easy tender relationship — the actors seem keyed to each other’s thoughts. Though she loves her dad, she slowly realizes that his damaged psyche doesn’t have to be yoked to hers. Of all modern feminist directors, Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone) is the most mournful. Her heroines don’t move on happily, but they’re responsible for themselves, kids, and, implicitly, the life of the species. So move on they do. —DE

Love After Love

It’s swimming with hate, much of it self-hate. Russell Harbaugh’s extended-family psychodrama charts the impact of a father’s death on a verbally abusive child-man (Chris O’Dowd), his arguably too close mother (Andie MacDowell), and another son (James Adomian) who is staggeringly drunk at an engagement party and pees on the guests’ coats. Watching them flaying one another (and bystanders) is a masochistic experience, but not an emptily masochistic one. And if you think MacDowell can’t act, well, you’re mostly right, but here she’s superb, her placidity a form of passive-aggression. —DE

Loveless

The title of Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s wintry, symbolic drama of a 12-year-old boy’s disappearance denotes a state of mind, a lament, and an indictment of crimes against the human spirit that seem to emanate from the country’s current president. Here and in his last film, Leviathan, Zvyagintsev anatomizes a spiritual disease for which a partial cure will be more movies like his. —DE

Minding the Gap

A decade ago, Bing Liu of Rockford, Illinois — ranked the country’s second most dangerous city among those with fewer than 200,000 souls — began filming two of his skateboarding buddies, Zack and Keire, and his documentary is full of marvelous, hot-dog skateboard montages. But these are contrapuntal notes, liberating flurries of motion in a powerful saga of kids who were — and in some cases still are — miserably stuck in place. Liu’s real story is childhood abuse and its frightening legacy. The movie builds towards a triple catharsis as each of the protagonists (Liu is the third) attempts to reckon with what he has endured — and what he might do to his own partners and children. —DE

Night Comes On

Actress Jordana Spiro’s inspiring directorial debut is shaped like a revenge film, but its rhythms come from the young black actresses at its center: Dominique Fishback as Angel Lamere (symbolic name alert!), fresh from a juvenile detention facility and all hard edges, and Tatum Marilyn Hall as Abby, the kid sister with a soft face and presence. There’s a Sundance Screenwriting Lab tidiness to the film, but the emotions onscreen are unruly enough to overcome the fine carpentry. Though slow, it’s intense, and you’re hooked from its first scene to its last, wrenching image. Like Moonlight, Night Comes On takes much of its soulfulness from la mer and people’s capacity for rebirth in its waters. —DE

Paddington 2

Children — and adults — deserve more movies as generous and lovingly made as Paddington 2. The sequel follows the template of the original almost to the minute, but manages to inject even more fun, freewheeling energy into each beat. In this installation, the Peruvian bear voiced by Ben Whishaw tries to find a job and winds up … enacting prison reform instead? Director Paul King still has loads of visual tricks up his sleeve that never feel too imposing on the story, and Hugh Grant gives one of the best unqualified performances of the year as a washed-up actor Paddington runs afoul of. The whole thing is a delight from start to teary-eyed finish. —EY

Shirkers

Sandi Tan’s idiosyncratic, dreamy excavation of the would-be punk cinema masterpiece she wrote and shot with her friends in the summer of 1992 contains multitudes. It’s an intriguing whodunnit about the mysterious man who entered her life and cut her cinematic dreams short, but it’s also a glorious celebration of youthful rebellion and creativity. The footage of the original Shirkers — whose mere existence is not as much of a spoiler as it sounds like — tells Tan’s unusual tale, and is a shimmering, melancholy time capsule of an adolescence and a country long since rendered unrecognizable. —EY

Sorry to Bother You

Boots Riley’s raucous arrival as a filmmaker is the take-no-prisoners punk film that 2018 deserves. The story of an flailing telemarketer (a never-more-squirm Lakeith Stanfield) who finds himself catapulted up a nefarious corporate ladder is bursting with visual and auditory ideas that feel instantly iconic — from the protagonist’s “white voice” (courtesy of David Cross) to Tessa Thompson’s literal statement-making jewelry. Sorry to Bother You is angry, hilarious, and never nihilistic, even as it takes a third-act turn that is still too unbelievable to spoil. —EY

Support the Girls

Regina Hall is magnificent in Andrew Bujalski’s pleasantly shambolic day-in-the-life of a Texas “breastaurant.” As the manager of Double Whammies, her day veers from wrangling her staff (including Haley Lu Richardson and the rapper Shayna McHayle a.k.a. Junglepussy, both terrific), to avoiding the wrath of the restaurant’s owner, to managing her own messy home life. But Bujalski’s film doesn’t come off as an airing of grievances; rather, it’s a straight, sober look at the invisible art of emotional labor. —EY

Suspiria

Luca Guadagnino’s gorgeous, shrieking reimagining of Dario Argento’s giallo classic will not be for everyone — it’s a cold, stately, anti-patriarchal thesis paper on trauma and dance and the horrors of 20th century Germany with one of the most gruesomely violent scenes of the year tucked into its first act. But what a thrilling swing, as bold in its content as Argento was in style (and just about as bold in style.) Dakota Johnson stars as Susie, an idealistic American drawn to the Markos Dance Academy in Berlin, where she quickly rises up the ranks, even as the dark magic within the school claims more and more victims. It may look daunting, but the two and a half hour runtime is the least scary thing about it. —EY

The Death of Stalin

Armando Iannucci’s acid satire charts the days in 1953 when the Soviet Union lost its paranoid-psychotic leader of three decades and members of his inner circle argued, plotted, and killed a lot of people while selecting a successor. The joke is that the characters (played by the likes of Steve Buscemi, Jeffrey Tambor, and Simon Russell Beale) order torture and mass murder in the prissy, peevish accents of Cockney or American bureaucrats, creating a colossal disconnect between small-minded egotistical clowns and the large amount of horror they have the power to inflict. If there’s a single theme, it’s the disfiguring effects of terror on the simplest human interactions. It’s farce transformed into collective tragedy. –DE

The Final Year

Greg Barker’s quietly devastating behind-the-scenes documentary tracks the Obama administration from late 2015 to the early morning of January 20, 2017, with special attention to U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power, Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes, and Secretary of State John Kerry. It’s their last chance to cement a foreign-policy legacy as the clock ticks down — although as we watch, we know what they don’t, that the next president will be insanely bent on undoing everything they’re trying furiously to accomplish. The film has been unjustly criticized as Obama propaganda, but it’s haunted by a tragic failure: Power’s inability to prevail on the president to intervene forcefully in the humanitarian crisis in Syria. —DE

The First Purge

The fourth installation in James DeMonaco’s increasingly close-to-home horror–sci-fi concept is an origin story of sorts for the franchise, taking place in the even nearer-future Staten Island. But the story of how an ultra-right-wing administration uses a disenfranchised community as a testing ground for their gruesome human experiment is less about the violence that supposedly lurks in all of us, than it is about the people who need us to believe in that violence in order to maintain their power. It may end up being the most inflammatory political film of the year (that’s not named Sorry to Bother You). —DE

The Hate U Give

George Tillman, Jr.’s adaptation of Angie Thomas’ bestselling Y.A. novel flies leaps and bounds over any expectations of what that genre and demographic demand. The Hate U Give, the story of a young black woman’s radicalization after a police shooting hits extremely close to her and her community’s home, is a contemporary epic, endlessly complex and mature, while not above indulging in the occasional dollop of teen-movie schmaltz. Amandla Stenberg’s thoughtful lead performance blooms into top-of-her-lungs passion in the film’s final act; it feels like the true grown-up arrival from her that we’ve been waiting for. —EY

The Rider

What’s so subtly special about Chloé Zhao’s intimate, lyrical film is the way it takes what easily could have been reportage and turns it into modern American myth. Injured cowboy Brady and his rodeo riding friends live in a milieu both quintessentially American and completely obscure to most 21st-century Americans. And yet, their story will feel immediately relatable to any person — or country, for that matter — that has ever had to accept a fundamental change or loss or blow to their sense of self. —EY

The Wife

The Wife is based on a nearly 15-year-old novel by Meg Wolitzer, but I recommend going in with no knowledge of the plot, if possible. The story of a writer (Jonathan Pryce) traveling to Stockholm to receive a Nobel Prize, along with his faithful wife/assistant Joan (Glenn Close), unfolds with high-minded luxuriousness and steadily mounting intrigue about what’s really going on in his wife’s head. Director Björn Runge and Close do such patient, simmering work in letting Joan’s secrets and hidden frustrations inch into the light on their own, that by the time the dramatic fireworks hit, each feels satisfying and earned. —EY

Three Identical Strangers

In Tim Wardle’s knockout doc, triplets adopted by three different families meet by chance in the late ‘70s, bond as if they’d known one another all their lives, and become a media sensation. But what begins as a goofy, Parent Trap-like tale drifts into darker waters — from a secretive adoption agency to nature-versus-nurture study overseen by a Strangelovian Austrian Holocaust refugee. First, nature seems dominant. Then nurture makes a comeback, big time, as the brothers’ existential anguish holds us spellbound. —DE

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

As a teenage romantic with a secret stash of unrequited love interests, Lana Condor is a ready-made star, and Noah Centineo rises to meet her as the adoring, throaty lunk any introverted girl dreams of coming around and melting away her shyness. Theirs is a teenage romance we can believe in, despite its ridiculously convoluted circumstances, on the merit of the leads and Susan Johnson’s effervescent direction. And when was the last time you believed in a teenage romance!?

Upgrade

Leigh Whannell’s grubby sci-fi horror yarn about a man implanted with a Siri-like AI in his nervous system is the kind of thing they don’t make nearly enough of any more — less Charlie Brooker, more John Carpenter. But aside from its gory, chop-socky delights (turns out AIs can be very helpful when you have some vengeance to exact), the film — and Logan Marshall-Green in particular — is often transcendentally hilarious, and its gruesome slapstick gets at some all-too real truths about the horrors we wreak when we let our digital aids do our dirty work. —EY

Wildlife

Carey Mulligan gives the major performance we’ve been waiting for in Paul Dano’s grimly fascinating — and often plain grim — adaptation of Richard Ford’s novel. She plays a beautifully-coiffed 1960 “homemaker” whose failed golf pro husband (Jake Gyllenhaal) elects to join a fire brigade in the distant mountains, leaving her with a 14-year-old son (Ed Oxenbould) and lots of bills. Before the boy’s horrified eyes, she gravitates towards her employer, a much older man (Bill Camp) who’s unnervingly comfortable taking advantage of her. Zoe Kazan co-wrote the script with her Ruby Sparks co-star (and partner) Dano, and it’s brilliantly attuned to all the roiling psyches. —DE

Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

Morgan Neville’s surprisingly moving doc sets Fred Rogers side by side in the multiplex with Han Solo and various Avengers—and guess who seems like the bigger superhero? Telling the story of a man and a kids’ show that, in the words of one director, “took all the elements that make good television and did the opposite,” Neville gently eases us into a neighborhood-as-world in which all talk is soft; all fantasy is plainly handmade, as if by a child in a playroom; and the most important thing is that no matter how we look or feel (sad, mad, plaid), we’re special, each of us, loved unconditionally by this nice, nice man. It’s a wonderful breather from reality, from which you come back more conscious of — and dismayed by — the hate that now runs the world. —DE