Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

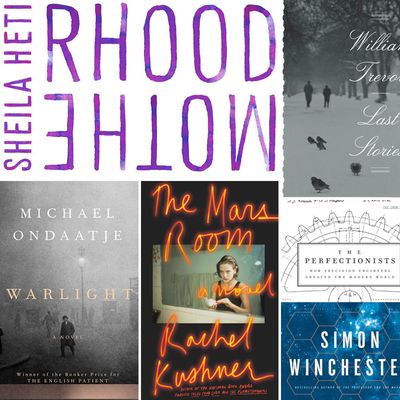

The Flamethrowers, Kushner’s glorious novel, had flashes of dark violence (it was about ‘70s radicals), but also romance, idealism, and virtuosic writing. Her new novel, set in largely in a women’s prison and centered on a San Francisco stripper with a horrific past, mines a segment of American society that’s grown up with almost no room to maneuver, no physical or spiritual escape. Kushner’s writing is brutal and spare, but she never condescends; even her most pitiable or evil characters make choices, have minds, entertain hopes. She renders them visible, then compels us to look.

Writers have lately addressed race with funny twists and surreal tropes — but not Brinkley, whose debut collection of stories lays out deeply realistic characters (mostly black men in Brooklyn and the South Bronx). The star of the title story is a janitor who muses on his reputation for good fortune; older African Americans in “Clifton’s Place” confront the onslaught of “revitalization”; an ex-con considers embarking on a new life with an old friend’s widow. Their very different struggles are all complicated by race and all in some way about coming of age — whatever age that happens to be.

The title of Heti’s latest work of autofiction — a fashionable hybrid of essay, memoir, and novel — should properly end in a question mark like her last book, How Should a Person Be? The Heti-an narrator, gliding into her late thirties and partnered to a man with a pre-existing daughter, contemplates whether to bear children and upend her writing life. Heti’s aggressively ruminative avatar documents parenthood in her demographic as though it were a distant continent in a world without jet travel: the crossing would be perilous and irreversible, and require a lot of unpacking.

The English Patient fans won’t be disappointed in Ondaatje’s latest big-canvas narrative of life on the outskirts of a global conflict. What they might have forgotten is how good the author is at surprising shifts of perspective. Warlight starts in England at the close of World War II, when Nathaniel’s mother and father flea to Singapore, leaving the teenage boy and his sister in the care of neo-Dickensian rogues. But when their mother’s secrets eventually tumble out (she returns to England to fight the first salvos of the Cold War), the novel both deepens and accelerates.

Whereas Knausgaard’s world-famous semi-nonfictional six-part series My Struggle took off from the very first sentence, his new quartet of seasonal books only really gets going in this third installment. Following the essayistic jottings of Autumn and Winter, Spring is more or less a return to form — an excessively detailed evocation (in a good way) of quotidian experience, particularly the raising of a young daughter alongside a bipolar partner. Bonus — this one actually kind of has a plot. You might almost call it a novel, though the master of “slow fiction” probably wouldn’t.

The great and prolific popular historian illuminates a rather technical field that really did change the world — as when John Wilkinson perfected iron-boring, turning James Watt’s janky steam engine into a device that reordered the planet. Winchester, whose father was a precision engineer, skirts the legendary inventors in favor of people who either perfected machines or scaled them up — acts that could actually pull in opposite directions. Winchester juxtaposes Henry Ford’s mastery of interchangeable parts with the limited-edition hand precision of the Rolls Royce — both exemplars, in different ways, of capitalism at its best and worst.

The master miniaturist’s final stories, written before his death in 2016, were among his darkest. A morbid pall looms over even his stories of coupling, in which motives are generally transactional and never pure. People use and misuse and steal from each other: a prostitute swipes an amnesiac’s savings, a woman conceals her disabled cousin’s death to keep collecting the pension. But there’s always comedy, as well as Trevor’s genius for compression and sly wit — and in the end, a sympathy for both victims and perpetrators that enlarges our consciousness of internal lives.

The brilliant author famously followed up her cult-hit debut, The Last Samurai, with a slow-burn breakdown as her second novel (Lightning Rods) almost fell victim to a publishing merger. Here she finally takes her revenge, with thirteen ornery but self-aware stories about the vultures who tear apart our culture. Artists resist the money-changers via the art of self-sabotage, which ranges from craven capitulation to, say, an unhealthy obsession with mathematical formulas. There’s some bitterness here but no sanctimony, because the author is almost as funny and self-deflating as she is smart — which is saying a lot.