In Alex Strangelove, the teens swear. And not just in a PG-13 “one fuck limit” (i.e. “Am I a bet, am I a fucking bet?”) way — in constant, squirrelly, often disgusting, pretty fucking true-to-life way. I found myself racking my brain for the last time I’d seen this much explicit dialogue in a teen movie, and came up with Cruel Intentions, a film about the depraved, sexually conversant offspring of Manhattan billionaires, and a rare R-rated teen movie. Most theatrical teen films can’t afford to block that huge a chunk of their target demographic from buying a ticket; this had me wondering if this was something Netflix was going to be good for — accessible teen fare that inches, in some regards, at least, to veracity with the messiness of teen life.

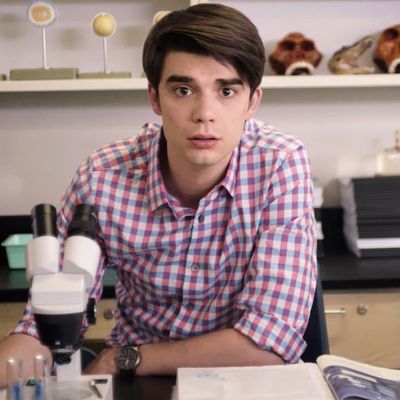

The film follows Alex Truelove (Daniel Doheny), the kind of affable, everybody’s-kind-of-friends with him guy; popular enough to be elected class president, not popular enough to have had sex yet. He’s a bit of a nerd (the science-y kind; he’s obsessed with cephalopods,) but not too socially awkward to have a girlfriend, Claire (Madeline Weinstein). We never see him bullied in the present day, there is nothing particularly tragic about his middle-class existence. As his buddy Dell (Daniel Zolghadri) points out, their school is relatively open-minded when it comes to sexual orientation and gender identity — “Why can’t anyone just be straight!?” Dell laments, like a bewildered senior citizen scrolling through Tumblr. But unlike, say, Love, Simon, a movie Strangelove will certainly court comparison to, the comfort Alex is afforded is not in pursuit of some insistent “he’s just like you!” blandness. There are too many things about Alex, played with neurotic sweetness by Doheny, that are utterly specific (again, the cephalopods). He’s not neurotic to the point of caricature, he’s comfortable at a stoner-y theater-kid party and dancing at a concert in the big city. There’s a genuine sense of a person in progress.

Alex is consumed by the fact that he hasn’t had sex yet, made worse by the pestering of his friends. He and Claire have positioned themselves at a remove from the more carnal aspects of teenager-dom, showing up for all the school dances in jokey costumes, and commentating on their more lascivious peers on their wildlife-documentary-style YouTube channel. (The YouTube material, which comes back as a thematic button in the film’s final moments, feels a little extraneous in what otherwise feels like a pretty timeless narrative.) They have decided they are above sex, which of course is easily recognizable as barely concealed terror. When they finally decide they’d better do it, and make big plans for the occasion, Alex begins to think about what he really wants, something further complicated when he meets a cute guy from another school over a passed joint at a theater-kid party.

Written and directed by Craig Johnson, Alex Strangelove is a coming-out narrative, and as such it can’t help but hit a lot of familiar beats. But its script feels personal, and less airbrushed than most in its recollection of the utter uncoolness of being a teenager. It’s sex-obsessed in the kind of cringe-y, clueless, completely uncynical way that is rarely seen in film and TV; its characters are not mouthpieces for the adult writer behind them, but actual attempted approximations of what it’s like to be a 17-year-old virgin. And it happily doesn’t fall into the trap of having every scene be about Alex’s impending revelation about his sexuality — there’s plenty of life happening all around him, including a more or less inconsequential, but nicely realized side plot about Claire’s relationship with her ailing mother. Weinstein is particularly fantastic in the film, playing a role that is very similar on paper to her turn in last year’s Beach Rats (which she was also great in) but miles apart at the same time. It’s clear that Johnson cares about her as much as Alex, which only makes us care more about both of them.

Alex Strangelove is a little stylistically unambitious, nor is it terribly compelling as a romance — who Alex ends up with is ultimately beside the point. That’s a smart decision, if a visually uninteresting one; there’s very little subjectivity or impressionism to its roil of adolescent emotions. But after a stumble with the middle-aged cranks in Wilson, it seems abundantly clear that a little earnestness is a good look for Johnson.