All this week, we’re publishing a series of pieces to accompany our New York cover story going behind the scenes of Netflix.

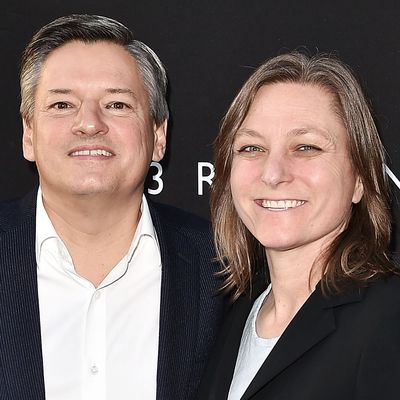

Before they were partners, Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos and original content VP Cindy Holland were (friendly) rivals. In the late 1990s, “Cindy and I were the only two people in the world buying DVDs for online video services,” Sarandos says. “I was doing DVD-by-mail for Netflix and Cindy for Kozmo.com.” Kozmo didn’t last; Netflix became, well, Netflix. Holland and Sarandos would end up transforming Netflix into the one of the most prolific producers of television programming in the medium’s history. “They’ve created their own culture,” says producer Ryan Murphy, who’s got two shows in the works at Netflix and next month begins a $300 million overall deal at the company. “And a lot of that culture, I think, is a hybrid of Ted’s showmanship and Cindy’s beautifully modulated creativity.” As part of my deep dive into Netflix’s binge factory, I sat down with Sarandos and Holland to talk about the origin story of their working relationship and how it’s evolved as the company has grown.

So after Kozmo shut down, Cindy went over to Mutual Films Company. How did you then end up finally working together?

Ted Sarandos: This is total happenstance, but back in the day I used to get a lot of DVDs handed to me. People would see me out, or at a party, and filmmakers would submit independent stuff. Someone handed me a DVD that was a documentary about Kozmo. And in the video I see Cindy sitting in at one of the meetings at Kozmo. It jarred my memory, like, “Oh, I wonder what Cindy’s up to?”

I called her and said, “Hey, I wonder if you still want to talk about coming to Netflix, blah blah blah.” We were literally sitting 50 yards apart. She was sitting in an office 35 steps probably from where I was, and we’re talking on the cell phone, she’s describing where she was at Mutual Films, and I said, “No, that’s where I am!” (Laughs.)

Cindy Holland: “Where?” “Raleigh Studios.” Where?” “This building!” “I’m right next door!”

That literally is L.A. Story.

TS: One-hundred percent. And the rest is history. We shared that office for a long time. It was just the two of us in L.A.

CH: We both worked together on buying DVDs from the studios, negotiating revenue share and deals. On the side, we were always finding cool projects, documentaries, foreign films, little indie films that we would then put on DVD. That was one of the things we really appreciated about each other when we first met — that love of independent films and documentaries and foreign films. “Hey, did you ever see this one or that one?”

At some point, you made the call to move Netflix from DVDs into streaming. What spurred you to make that leap?

CH: At the end of 2010, we were having conversations about what the five-year plan would be in the licensing TV from existing networks business, because that’s what I was overseeing at the time. We predicted there would be a time when a number of them would want to stop licensing to us because they wanted to preserve the content for their own, over-the-top [service].

TS: If we believed our own narrative, which was that TV would evolve to entirely be direct to consumer and on the internet, then the networks as they exist today would be direct to consumer on the internet. They wanted to keep their programming, not sell it to us. There was no evidence of it at the time; it was just a gut feeling.

CH: Amazon was spending money, Hulu had already been spending money. Pricing on second-run TV [syndication] was climbing rapidly, particularly for the top shows. We started looking at it, and we could see that the economics in second-run TV were heating up to the point where it might make sense for us to do first-run TV, because your economics would be a wash.

Once you decided to jump into streaming, how did Cindy end up running that division? At the time, it was seen as sort of a niche; DVDs were the heart of Netflix, and Cindy was key to that business.

TS: When we started doing original programming, it was a pretty small subset of the total spend, original versus licensed goods. I think we had a $10 million budget our first year for streaming [before House of Cards]. Cindy had already had this incredible reputation for her taste and her ability. [She can] read a script fast and immediately dissect it in her head — what’s broken and how to fix it and all those things. I’m not a disciplined reader. I can tell you quickly that something’s broken, but I’m not so fast as to tell you why. So I was always blown away by the skill, which I didn’t even know at the time was one of your first jobs in Hollywood — covering scripts!

CH: It’s a hidden talent. I had to dust it off!

TS: When it came down to, “We have to hire a head of original programming,” Cindy said, “I want to do that.” But at the time, it was in addition to the licensing. And I said, “We need to focus, so I really want to double down on specialization. If you’re willing to walk away from the other thing to do this thing, even though it’s just a test.” Cindy said, “I am willing to do that.” It was a pretty big professional bet for her — to already be running one of the largest TV-buying organizations in the world at this time, and then making that switch over to do this thing that may or may not work out.

What’s your daily interaction like these days? How do you lean on each other, and what do you take from each other in your relationship?

CH: We’ve either shared an office or had offices next to each other for 16 years, so we spend a lot of time together, and we still do. We both travel a lot, so not quite as much, but we have an unofficial routine: We’re generally both here early in the morning, we’ll talk about whatever’s going on … just to touch base, but it’s not formal.

Ted, do you still go to a lot of pitch meetings for new projects?

TS: A couple.

CH: We’ll both go to the more high-profile ones, but we’ve also been clear with all the sellers in town that neither one of us has to be in a room for a project to get green-lit and happen here.

TS: That’s what enables the speed to market. I feel like we’re more engaged in the fire drill of a show versus the day-to-day running of a show. When something breaks or is perceived to be pretty high-risk one way or the other, that’s when we go there, and that’s why it’s great when we have shorthand.

You guys move fast, but do you ever take a minute to reflect on how much Netflix has accomplished in seven years, and how big you’ve become?

TS: I try not to. Being here as long as I have, every two years it feels like a completely new thing we’re doing, from the DVD-by-mail, domestic-only business to streaming to international to movies to international original series. It’s a constant new thing. The scope, scale, reach, and impact year on year keeps growing to a point where I’m glad I never stopped and said, “Mission accomplished,” because there’s always the next thing. It doesn’t give you that much time to do a victory lap. We’re still in a rapidly growing business.

CH: We work well together because neither one of us is ever satisfied. We have a company full of people who are never satisfied. We do try to stop and celebrate milestone things, like the ending of a show or a particularly successful one, but we’re in this for the long haul, and we’re focused far into the future at this point.

Five years from now, will we not recognize Netflix?

TS: Remember, when we started this, Blockbuster was as big a beast as we could imagine. That was an $8 billion company when we started, and we thought, “Oh, if we could only get there!” When we started doing originals, I would have never, ever bet that we would have three series up for best series at the Emmys that we’ve had the last two years. The speed in which we were able to do this is one of those things where if I did stop and think about it, I’d have to stop longer and think about it, so I don’t want to do it.

CH: It’s probably going to be better and bigger than my imagination.

You mentioned Blockbuster. Isn’t their demise a cautionary tale about how companies so big can get arrogant and fail?

CH: As long as we are a merry little band of outsiders, or as long as we continue to feel like we’re the Little Engine That Could, it’s less feasible that that happens to us. We just don’t have that mind-set.

TS: Somebody told me this morning, the town has a way of putting you in a bubble that removes you from the public and their tastes. You have to be so careful not to let that happen to yourself.