In 1987, the Nemo Press released The Essential Ellison: A 35-Year Retrospective, a collection of writings spanning the long career of Harlan Ellison. It speaks volumes about Ellison’s work that this attempt to distill his bibliography down to something that could be called “essential” still resulted in a book well over a thousand pages in length. (A subsequent edition, The Essential Ellison: A 50-Year Retrospective, is even longer.) Some writers’ greatest hits can be read over the course of a day; Ellison’s, this implied, was the stuff of seasons.

The size of his bibliography is one thing that makes discussion of the influence of Ellison, who died Wednesday at the age of 84, tricky. In terms of his prose, he worked primarily in shorter forms, winning a host of awards along the way; as a screenwriter, he wrote one of the most acclaimed episodes of Star Trek, “The City on the Edge of Forever,” along with several episodes of the 1980s revival of The Twilight Zone, and many other shows. In a 2013 interview with Damien Walter for The Guardian, Ellison estimated that, at that point in his career, he’d written around 1,800 stories, novellas, screenplays, teleplays, and essays.

Ellison’s short stories took wildly disparate approaches to the form. “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” a formally inventive story that gradually reveals itself to be about time travel, bears little resemblance to “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” a tale of a godlike artificial intelligence tormenting humans, shot through with a not insignificant account of body horror. While a survey of his most acclaimed fiction reveals little overtly in common, a sense of anti-authoritarianism prevails, something which is echoed in both the stories’ subject matter and in the often-inventive structures Ellison used to tell them.

This boldness with form wasn’t limited to his prose. Ellison’s unproduced screenplay adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (first serialized in 1987 in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, which provided my first exposure to Ellison’s work) took its structure from Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Finding common ground between a classic work of science fiction and a groundbreaking work of cinema is unexpected, but it ultimately works — and, perhaps, played a role in the gradual lowering of boundaries between genres across media. (See also the aforementioned “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” which appeared alongside works by the likes of Alice Munro, Lorrie Moore, and Mary Gaitskill in The Best American Short Stories 1993.)

Ellison’s primary literary legacy, though, may well be a broader aesthetic one — specifically, of showing writers that structural inventiveness, high concepts, and deft prose can all neatly coexist. One can see this approach in the work of writers as disparate as Kelly Link (in whose work Jeff VanderMeer found parallels to Ellison in 2005) and Ted Chiang (who, like Ellison, had some fantastic work published in Omni magazine in the 1990s). Ellison opened a certain literary door; what we’ve seen in the decades since has been a flourishing of ideas and concepts, recombining in fascinating ways, that that opening created.

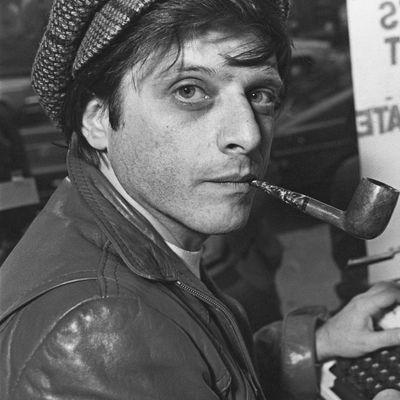

Ellison was also known for his larger-than-life personality. (“Nearly everyone who has been in science fiction over the last 60 years has a Harlan Ellison story, and I have two,” begins John Scalzi’s remembrance of him.) In screenwriter Josh Olson’s 2007 “The Life and Death of Jesse James,” a sinuous and harrowing nonfiction account of online impersonation and toxic behavior, none other than Harlan Ellison figures into the plot in a not insignificant way; were it a movie, his would be the plum supporting role that wins someone a late-career Oscar. There are few writers about whom this could be said; for Ellison, falling into such an archetypal role in a true story made perfect sense.

That outsize personality could cut both ways, however. A 2006 incident in which Ellison groped fellow writer Connie Willis while receiving an award at WorldCon — and Ellison’s subsequent response to it — was cringeworthy at the time, and has become even more so in the ensuing decade. (This 2014 essay by Nick Mamatas provides a good overview of instances of his bad behavior.)

A different aspect of his public persona may provide the most significant, and unexpected, component of his legacy. From the 1970s onward, Ellison would periodically write stories in the windows of bookstores. In a 1981 interview, he spoke of doing it to demystify the process of writing: “I show people it’s a job of work like being a plumber or and electrician,” Ellison said.

Not every writer has access to a bookstore window in which to write, or can get writing prompts from the likes of Chris Carter or Robin Williams. But that sense of writing in public is something that, with the advent of social media, has increased exponentially: writers frequently post glimpses of works in progress, updates from their desks, and photos of them at work. It’s not quite the writer as public spectacle, but it’s also not far removed from it.

Ellison’s take on writers online was sometimes contentious — “I think any writer who gives away his work demeans himself, demeans the craft, demeans the art, and demeans the buyer,” he said in 2013 — and yet, that aspect of his writing career translates neatly to the online sphere. If that seems contradictory or paradoxical, it’s certainly not the only part of Ellison’s legacy about which that could be said.