Looking for some quality comedy entertainment to check out? Who better to turn to for under-the-radar comedy recommendations than comedians? In our recurring series Underrated, we chat with writers and performers from the comedy world about an unsung comedy moment of their choosing that they think deserves more praise.

You’d be hard-pressed to find someone working in comedy that hasn’t creatively cribbed from Monty Python. The influential British comedy troupe’s trademark surrealism, self-referencing, and artistic anarchy has been coded into the DNA of many modern architects of America’s absurdist comedy Zeitgeist, from Doug Kenney to Amy Sedaris to the minds behind Mr. Show. With Flying Circus, Python reconfigured the stuffy structure and unadventurous format of the modern sketch show, thumbing their noses at the medium by acknowledging its limits then speeding past them completely. Sketches would connect, reference each other, and bend time and space but would never fully conclude or tie up loose ends. It was an exercise in creating a lattice of meta-narrative and self-aware characters, which ultimately established its own extended universe of comedy iconography that is still being cited nearly 50 years later. I mean, the Dead Parrot sketch is just straight-up foundational.

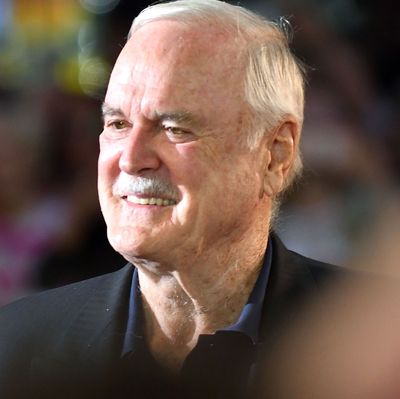

But beneath Python’s Dadaist deconstruction of comedy trends (sideways credits FTW!) was a mean anti-authority streak. Their films were big and silly, yes, but their themes took direct aim at nationalism and war (Holy Grail), dogma and religious fundamentalism (Life of Brian), and class (Meaning of Life). Founding Python member John Cleese made this clear during our conversation, telling me that “anti-authoritarianism was deeply ingrained in Python” growing up in post–World War II United Kingdom.

Cleese, who is currently on tour screening Holy Grail followed by career-spanning conversations with audiences, wanted to pay homage to the stylistic forefathers of Python, The Goon Show, for our Underrated series. Created by British-Irish satirist Spike Milligan along with Harry Secombe and Peter Sellers, The Goon Show disrupted the most dominant entertainment format of the ’50s — the radio show — with a cast of fictional characters (with Sellers, Secombe, and Milligan embodying multiple personalities) performing scripted three-act shows parodying aspects of modern life and mocking show business, the military, advertising, and English culture along the way. The Goons also used music and sound effects in innovative ways, creating a more surreal and heightened atmosphere unlike anything else on the BBC Home Service at the time. Picture A Prairie Home Companion on acid, or Tim and Eric distilled into audio form. Cleese claims the Goons had the greatest impact on the troupe, and after hearing him speak about them, it’s easy to see why.

It’s impossible to overstate how influential your body of work — from A Fish Called Wanda to Fawlty Towers to especially Monty Python — has been on modern comedy. But what comedy inspired you growing up that your fans may not know about?

Well the biggest influence, and this might surprise you, is not something we were watching. We were listening to it because it was a radio show. It was a radio show in the ’50s called The Goon Show. It was a pure radio show and we all were listening to it. Kids were devoted to it in England. It was written by a guy who was a bit of a genius, rather a depressed one of course, named Spike Milligan. It also had Peter Sellers in it, who of course is the greatest voice man of all time. If he could listen to you for five minutes, he could do a perfect impersonation of you. He had this wonderful program he created which allowed him to experiment with his insanely funny characters. We used to listen to that in the same way that people listen to Monty Python. In the morning, we’d be at school and we’d discuss the whole thing and rehash the jokes and talk about it. We were obsessed with it.

What was it about The Goon Show that you gravitated toward?

It was absurdist. It didn’t try to be intellectual, yet it at its core it still was. I always had an affinity for the silly, and the humor of The Goon Show was just that. It was also very subversive. Spike and [co-creator Harry Secombe] were in the armed forces during the Second World War, you see, and they had developed a rather disrespectful attitude towards authority and the officers, and that was always coming through in the show — just a disrespect for the pompous old-style English guys and the upper class. And that anti-authority really spoke to us [in Python]. People used to ask us to describe what sort of humor Monty Python was because they didn’t know how to categorize us. We’re just silly. Other people who come across us can give us labels if they want.

Was that your first introduction to Peter Sellers?

Oh yes, that was where he started. Then he made some very good English comedies, and then he made one or two extraordinary ones like Dr. Strangelove. You’d be impressed to know that I used to write film scripts for him with Graham Chapman. We all wrote together. Only one of them was done and it was … pretty terrible. It was called The Magic Christian. I worked with him and I very much liked him.

What were your feelings towards American humor at the time? Could you find any symbiosis between your distinct British sensibilities and American comedy?

I grew up watching more American television than English television. In the ’50s, I used to watch George Burns, Jack Benny, Phil Silvers, Amos ‘n’ Andy, and, of course, Joan Davis. I especially loved the big musical-comedy films every summer with Danny Kaye. So I was very aware of and in tune with American humor. Then as I got into my late teens, the most exciting humor was coming from America, but in those days it was over gramophone records. I used to listen to Mort Sahl, Shelley Berman, Bob Newhart, and Nichols & May — these extraordinary talents, and they would perform all different types of humor. You couldn’t label it. Lenny Bruce even. You couldn’t label it because they were all so different. It was far more intelligent and much more lively than anything we had going on in England.

Then English humor started to get very good after that point because it became a mixture of that forward-thinking style and all the great old vaudeville people. You had an enormous number who’d grown up entertaining the troops in the Second World War and then much younger people, a lot of them coming out of Oxford and Cambridge, starting with the genius satirist called Peter Cook and his friend Dudley Moore. Then following Monty Python there were a couple of generations of people after us who did a blend of all this and made their way to [American] show business. It was a golden age of probably 25 years, then there was a brief return to that phase in the ’90s.

Is there a comedic performer or comedy writer that you’re particularly impressed by today?

No, and I’ll tell you why. It’s because as you get older, and after you’ve spent your life doing comedy and not much else, you mainly get excited to do other things. I’ve written a couple of books on depression and on psychology. I lecture on creativity. I’m a phony professor at Cornell. I go and talk to them about things that interest me. I’ve just seen so much comedy that now that I’m older, it’s very rare to come across someone who’s a true original. I remember how enormously exciting it was to first discover Buster Keaton or W.C. Fields or the Marx Brothers. But there was a wonderful social critic called Bill Hicks — he must have died 20 years ago, but he was a young fellow. I really thought he was wonderful. I think he is harder style, much harder than mine, but very strikingly his own. He impressed me.

You’re participating in an upcoming retrospective series at the Kings Theater in Brooklyn where you’ll be screening Holy Grail and following it with a thorough oral history of your storied career. I read on the press release that you only want absurd questions during the Q&A. Care to elaborate?

To express it another way, I would like disrespectful questions. What I hate is getting someone from California telling me how wonderful I am or asking for advice on how to be as wonderful as I am. That’s awful. I like rude questions, like “Why can’t you stay married?” or “Why is [Michael] Palin so much funnier than you are?” It doesn’t have to be respectful. In fact, my daughter will be the questioner. She’ll be in charge of which audience inquiries are good enough because she has no respect for me at all. You see, the problem with most interviewers is they’re much too respectful.

Why’d you decide to screen Holy Grail for this tour and not, say, Life of Brian or The Meaning of Life?

There’s a simple answer to that: It’s the film that is most popular in America. My favorite film of ours is Life of Brian. I do think it is a better film. I think it’s a much better story and it’s also about something important. It’s a more interesting subject. But the fact is — and I’m very grateful for this — Americans seem to love Holy Grail. They sell out tickets for a showing so much faster. Holy Grail was our very first film together as a troupe and the first major thing we did after Flying Circus, so it’s an easier gateway for the audience to ask questions about Python’s history. But sometimes people just want to ask about the other things that I’ve done in my career. We also talk about politics, or what’s going on in society, or what makes me laugh, or the parameters of political correctness — all those kinds of things. These conversations get really interesting.

Is there a cardinal rule of comedy that you lived by that you would encourage aspiring comedic performers to follow?

I think the most important thing that you can do is get in front of an audience, because you have to develop a style. You can’t be one type of a performer one night, and another kind of performer on the next. The only way you’re ever going to develop your style is by being in front of an audience. I suppose if you’re just a writer, then that’s different. You can develop it there on the page, and of course, writing, I always advocate. I recommend trying to write if you can, because if you’re just a performer, you’re entirely at the mercy of the whims of the world. Somebody might write you something, but suppose if they don’t? Try to write something yourself. Have a go at it yourself. It’s not easy to write original comedy. You just have to work it out and fine tune it in front of an audience. You mustn’t be frightened of failure. The only way to avoid failure completely is to go at it the exact same as you’ve always done it. If you do that, you’ll never fall flat on your face, but you would never do anything interesting either. So you mustn’t be too frightened of failure. It’s embarrassing when you tell a joke and people don’t laugh. You just have to learn to deal with that. Move on quickly to the next joke.

Here’s a fun thing: There’s an exercise that people can do which I think is very valuable. In my day, I used to do it with gramophone records but now you can do it with clips. Take a scene that you love that’s been done by one or two people that you also particularly love. Watch it again and again and again until you’re no longer amused by it. Watch it so many times that you don’t actually laugh at it. When you start laughing at it again, that’s the moment when you start typing out how it’s done.