At a studio in 2016, Dave Longstreth was working by himself on a chord progression, as he usually does when writing for his band, Dirty Projectors. “It’s normally a pretty solitary process,” he says now. But that time, Solange was there, as were Sampha, a British songwriter and producer; Blue, Solange’s engineer; and a bunch of other creative people, all part of what Longstreth calls “the camps,” to make Solange’s 2016 album, A Seat at the Table. “I’d have a melody from her, and would be just harmonizing on it, and she would come over and say, ‘Ooh, I really love this chord and that chord, but this one is too dissonant,’ ” he recalls. “To be just a spoke on the wheel was a novel experience, and to be thinking in a collective way was just really fresh for me.”

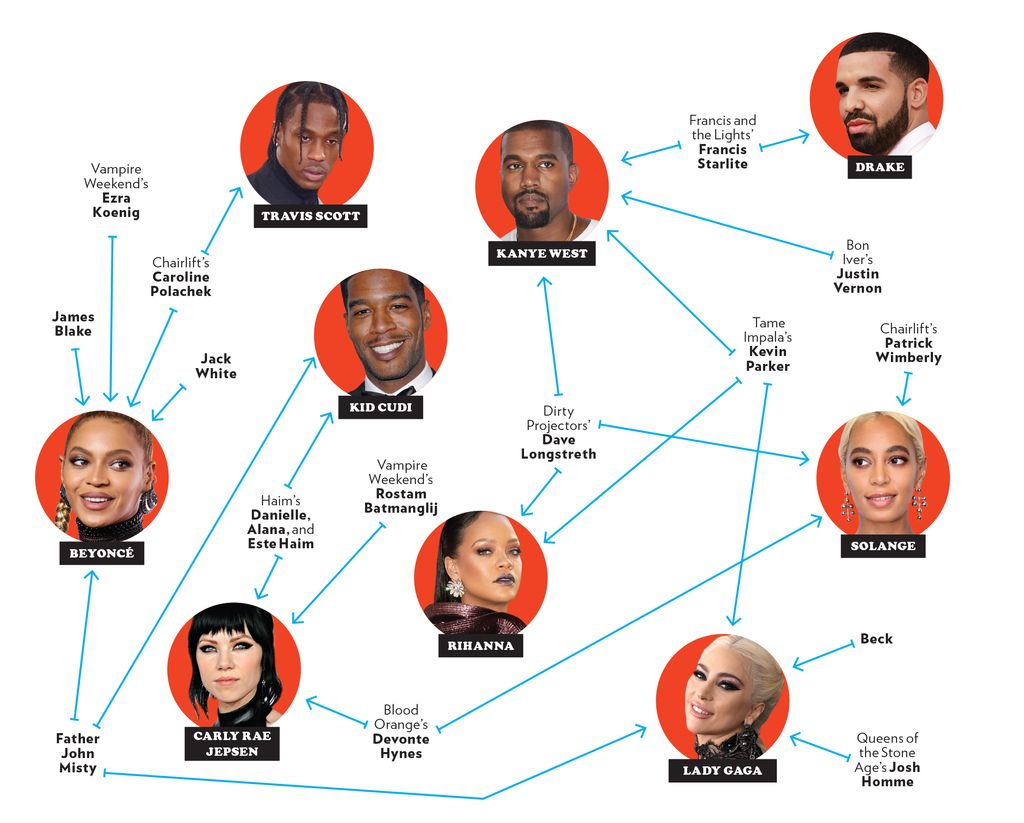

As long as there has been indie rock, songwriters have worked in their own band bubbles — it’s hard to imagine Michael Stipe taking a break from R.E.M.’s Document in 1987 to string together a few verses with George Michael while lounging in the south of France. But over the past decade, the genre’s biggest names, including Longstreth, Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig, Father John Misty, and Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker, have substantively contributed to albums by Beyoncé, Rihanna, Kanye West, Lady Gaga, and others. Many of these connections happen by serendipity — Beyoncé’s “They don’t love you like I love you” hook in “Hold Up,” widely thought to be about her husband Jay-Z’s infidelity, was actually the result of Koenig tweeting a slightly misremembered line from Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ 2003 single “Maps,” then recording it with Diplo.

Songwriting camps have convened since the early ’90s, when Police manager and I.R.S. Records chief Miles Copeland invited heavy hitters such as Cher and Squeeze’s Glenn Tilbrook to his French château. For Rihanna’s 2009 album Rated R, Def Jam Records chief Antonio “L.A.” Reid hosted what John Seabrook, in his book The Song Machine, called “the mother of all song camps.” Camps have multiplied since then: In June, Alicia Keys held an all-female retreat, called She Is the Music, at Jungle City Studios overlooking the Manhattan skyline; publishing giant Warner/Chappell Music invited 45 writers to Las Vegas; and independent label and publishing company Concord Music Group held one with 87 songwriters in Nashville to create music for movies, ads, trailers, promos, and TV shows (and has made $3 million so far from songs written at these “synch” camps). At an ASCAP camp in France, three veteran country writers penned “Somethin’ Bad,” which turned into a Grammy-nominated duet for Miranda Lambert and Carrie Underwood; Dua Lipa’s 2018 hit “IDGAF” came out of a Warner/Chappell camp in Las Vegas. “If you’ve got a huge song coming out of the camp, it’s definitely paid for the camp and probably beyond that,” says Kara DioGuardi, who has written hits for Pink, Kelly Clarkson, Britney Spears, and others and recently purchased a Nashville building to hold camps and other music-business events.

The camps, or at least the collaborative songwriting process, have fundamentally changed the way pop music sounds — Beyoncé’s Lemonade was a strikingly personal album, full of scorned-lover songs, but it was conceived by teams of writers (with the singer’s input and oversight). Key moments came from indie rockers, including Father John Misty, who fleshed out “Hold Up” after Beyoncé sent him the hook. Similarly, West’s Ye deals with mental illness and other intimate themes, but numerous writers, from Benny Blanco to Ty Dolla $ign, helped him turn those issues into songs. (Father John Misty, Parker, Vernon, Koenig, and other indie-rock stars refused interview requests.)

“Those artists still have a heavy hand in what songs they pick,” says Ingrid Andress, a Nashville singer-songwriter who is readying new solo material and regularly attends camps for pop stars. “But people forget that not just Beyoncé feels like Beyoncé. I guarantee all the people who wrote for Beyoncé’s record are coming from a place of also being cheated on, or angry, or wanting to find redemption in their culture.”

The camps aren’t for everyone. Madonna, who tends to collaborate with one or two producers at a time, recently complained on Instagram that she wanted to be “allowed to be a visionary and not have to go to song writing camps where No one can sit still for more than 15 minutes”; Oasis’s Noel Gallagher piled on Ed Sheeran and “the little fella from One Direction” for collaborating with numerous songwriters at a time. But Madonna and Gallagher are missing the central point of the camps — they’re not corporate factory farms where major labels crunch songwriting parts together and come out with chicken nuggets; they’re just another way to find that elusive spark, just as combos of jazzmen do onstage, or John Lennon and Paul McCartney once did when they stumbled onto the B7 chord in “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” DioGuardi compares them to the Brill Building, which housed songwriters like Carole King and Neil Diamond in the ’50s and ’60s. And Longstreth says, “When people look at things like that — ‘Oh my gosh, there’s 17 writers, what is music?’ — it’s a little bit misleading.”

“All the walls came down,” says Brett Williams, who manages Dirty Projectors and other indie acts. “Ten years ago, it wasn’t necessarily a trendy thing to do — have guys who wrote cool music also be writing songs for Britney Spears. Now it’s a selling point.”

When I walked into a room at the Lakehouse Recording Studios in Asbury Park, New Jersey, in late June, my eyes took a few seconds to adjust from the fluorescent hallway lighting. Through flickering candles, I made out Chelsea Jade, a New Zealand singer-songwriter, dressed in black, singing in a high, glassy pitch; Danny Mercer, a Colombian-American guitarist and singer, tapping out a Depeche Mode–style riff on a keyboard; and Randy Class, a Bronx producer, capturing everything on a laptop and looping it back. This was the BMI songwriters’ camp, which split up ten top writers into groups of three or more with the hope of regurgitating multiple daily songs. In this case, it was entirely songwriters and producers in their 20s and 30s; BMI put them up at a downtown hotel and arranged activities like a day of surfing. They worked hard (three writers struggled for half an hour over the line “This feels like a movie, right?”) and partied hard (my Friday-night interviews were full of background whooping).

At first, in their dark room, Jade, Mercer, and Class seemed disconnected, respectfully arguing about whether a man or woman should sing a line about crying, but they abruptly changed course and were now physically facing the same direction. Jade improvised: “I’m a psychopath.” Class quickly discerned a double meaning about a “psycho’s path.” Mercer fleshed out the melody with Spanish-guitar runs. I left before they finished, but it sounded like something Ellie Goulding could sing to airy dance rhythms.

The next room I went in had a different ambience. Four songwriters were jammed onto a couch, as producer Tim “One Love” Sommers cranked out synth chords near the doorway and caffeinated Joe Kirkland of the veteran songwriting duo Whiskey Water bounced around the room. I could see a half-finished bottle of tequila on top of one of the speakers. Singer-songwriters Olivia Noelle and Andress shouted the chorus: “I’m still fucked up from last night!” The other songwriters were all men, and they were waving their arms excitedly, adding to the momentum with lyrics and “whoa-ohs.” Kirkland came up with a chorus: “Who cares / Not me / We’ll make / It up / Eventually.”

Andress, 26, was the dominant figure in the room. She has an endearingly raspy voice (or did on that night), and her colleagues went silent when she spoke up. The Nashville singer had just been to Keys’s songwriting camp in New York, and I found out later from BMI executives that she had been the key “get” — the other writers agreed to attend the camp when they heard she would be there. Andress told me afterward she had a love-hate relationship with songwriting camps because she felt like she was sometimes writing for new artists who didn’t have a musical identity and relied on songwriters to establish it for them. “They’re artists! They don’t have time to experience real life!” she says. “I can’t even imagine having to be camera-ready all the time and then write a heartfelt song. I only write for artists who have a good idea of who they are. Otherwise, I can’t help them.”

Andress does, however, enjoy writing songs with friends, no matter who might eventually record them, and she was enthusiastically participating in the Friday-evening session. Amid cheers and chants in the room, she threw out this lyric: “I should say sorry, but Bacardi and me don’t ’pologize.”

The song sounded like something Kesha might have recited when she had the dollar sign in her name. At one point, Kirkland seemed to hint at who could sing it: “Bangerz! Bangerz! That’s the reason my dog is named Miley!”

Even before the songwriters took off on a Saturday afternoon, Samantha Cox, BMI’s vice-president of creative for New York, had been working her connections. She took a break from Asbury Park one day to hang out in New York with rising pop star Bebe Rexha, whom she knows, and her A&R man Jeff Levin. After she mentioned the camp, Levin told her: “I want to hear the songs.” Cox advises writers in camps to agree in advance to equally split song shares — a point Andress strongly agreed with — although once managers and attorneys get involved, negotiations often happen later. Writers may not get paid until the song begins to generate money through sales or licensing. “Is it going to cost me £1,000 to send the songwriter to the camp?” asks Kim Frankiewicz, Concord’s executive vice-president of worldwide creative. “We weigh it all up.”

This new lane of collaborative songwriting for pop stars comes at a crucial time for veteran indie stars — rock sales and streams have plunged from 29 percent of the overall record business in 2016 to just 21 percent last year, according to Nielsen Music. Meanwhile, Vampire Weekend hasn’t scored a gold record since 2014 and Father John Misty and Dirty Projectors have never sold more than 500,000 copies of an album. It can’t be bad financially for someone like Longstreth, whose music is idiosyncratic and full of off-kilter harmonies, to score a writing credit with Rihanna, McCartney, and West on 2015’s platinum-selling “FourFiveSeconds.” Longstreth and his manager, Williams, won’t say how much he made from that collaboration, which sprang from an impromptu gathering of writers and producers West held at a house in the Hollywood Hills, but it has streamed 475 million times on Spotify and another 393 million on YouTube.

“It can be lucrative, but it’s just a gamble,” Williams says. “Typically, our artists would take the lion’s share of a song — 80 percent or more. But Dave is in a room with Kanye, and Paul McCartney’s involved, and Rihanna, and all these other producers — you’re happy to get 10 percent.” If Longstreth’s cut truly had been 10 percent, the Spotify and YouTube streams of “FourFiveSeconds” would have made him around $25,000 or $35,000, depending on whom you ask in the music business. But, he says, “Economics has never been a super-driving measure of my choices, career-wise.”

Pop songwriting has been moving in a more collaborative direction for years, leading behind-the-scenes creators to scramble for credits — production duo Cool & Dre told Billboard that collaborating on an instrumental loop on the Carters’ Everything Is Love was “life-changing.” Drake’s “Nice for What” and Cardi B’s “Be Careful” list 16 and 17 writers, respectively. (Some are not new collaborators but authors of samples in the songs.) “Looking at the charts, nine times out of ten, pretty much everything is co-written,” BMI’s Cox says. “There’s at least three to four to five writers on every song that’s out there right now.”

Ben Dickey, manager of Future Islands, Washed Out, and other indie-rock stars, believes the trend begins with hip-hop, in which artists are more experimental and willing to take chances than those in any other genre. Whereas a songwriter in a rock band can be stuck in a routine, collaborating with the same people in the same configurations, West, Drake, and Beyoncé pick the best material from whoever inspires them at the time. “You come up with what can be a really interesting song that has way more diverse influences than what one singular singer-songwriter would come up with — then you have Kanye or Drake come in and rap over it,” Dickey says. If a songwriter swept up in their nets happens to be an established indie star, like Longstreth or Koenig, so be it.

Longstreth returned from his Solange and West camps inspired, telling reporters about the creative benefits of listening to music jointly with friends and collaborators. (With Solange, he got to work in New Orleans, Ghana, and elsewhere; Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, working on West’s 2010 album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, went to Hawaii. The high-end travel is no small perk for a songwriter.) To make Dirty Projectors’ recent album Lamp Lit Prose, Longstreth went back into solitary-songwriter mode, but he’d be enthusiastic about returning to a camp if he received an invitation. “There’s no real jamming as a songwriter, you know what I mean?” he says from his L.A. home. “This brought a feeling of spontaneity and improvisation to the process.”

The Freelancers

These pop artists have had songwriting help from indie rockers.

*This article appears in the August 6, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!