Would you give me a call—I need your opinion on something pressing—thanx.

Frank Langella’s email hits my in-box late on a Sunday afternoon in March. The subject line reads A FAVOR. In a few days, the actor will head west to begin shooting Showtime’s new Jim Carrey series, Kidding.

“I don’t see how I can do this,” Langella tells me the next morning, his familiar baritone pinched thin with stress. In Kidding — which premieres September 9 — Carrey plays Jeff Pickles, earnest host of a long-running children’s TV show and linchpin in the merchandising empire it’s spawned. Think of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and Captain Kangaroo combined, and you might approximate this slightly bent project from Carrey’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind director Michel Gondry and Weeds writer Dave Holstein. Langella, who has four Tony awards and an Oscar nomination for Frost/Nixon, will provide ballast as Jeff’s father, Seb, the pertinacious chief of staff determined to keep everyone — especially his sullen, fragile son — from jeopardizing their multimillion-dollar business.

Langella shares with me his dismay that in just the first two episodes, Seb gets attacked by a swarm of bees that swell his face red with stings that he’s furiously dabbing with pink Calamine lotion. And his first Big Speech ends with a kvetch about “a balloon of poop in my colon that’s gonna pop any second.” Here’s an actor whose moody Bogart eyes, set in a bejowled mask, have taken on an immutable aspect since his Nixon turn and his calm-the-waters spy-handler Gabriel in The Americans — and they want him popping cherry-colored dots like some vaudeville clown? I commiserate over the prospect of humiliation. It reminds me (and Langella) of Douglas Brackman Jr., the Alan Rachins character on L.A. Law, continually subjected to exploding toilets and other indignities. Beyond that, I hold my tongue. I’m not about to encourage him to give up a lucrative job.

Ever since he had asked me to be his biographer 18 months ago, I’d learned to listen as Langella worked through his demons and formulated the tale he wants me to tell. One of the most revered stars among the generation that came of age in the ’60s and ’70s, Langella thrived (and, not infrequently, faltered) on dangerous choices, professionally and personally.

“I want to be the animal in the jungle you watch,” he told me. “I want you on the edge of your seat from the moment I appear till the end. The experience for an audience every night has got to be catastrophically emotional on both sides. And the only thing that can do that for them is an actor who decides to go for their throats. I’m shocked and dismayed at how few actors want to do that.”

Although Langella often bounced ideas around his intimate circle of friends, he followed his own instincts. After all, hadn’t he published (in 2012) Dropped Names, a selectively revealing account of his sexual adventurism and conquests? And hadn’t some found it catty, even cruel?

Now he was ready for a fuller accounting, beginning with the arrival of an awkward, wonky kid from Bayonne, New Jersey, in New York City in the late 1950s, having survived adolescence with a suffocating mother and a philandering father whose business instincts had taken the family from near-poverty to considerable wealth and back. “When I was a kid my deranged mother would put me to bed in the late afternoon, after homework and a meager supper,” he wrote me in an email, “and I would lie in my bed listening to all the kids playing outside on the street in the sun. It was then, I think, I began to believe that I was not meant to be where there was laughter and playing — but alone in my imagination. It was then I began to feel I was not meant to run with the pack.”

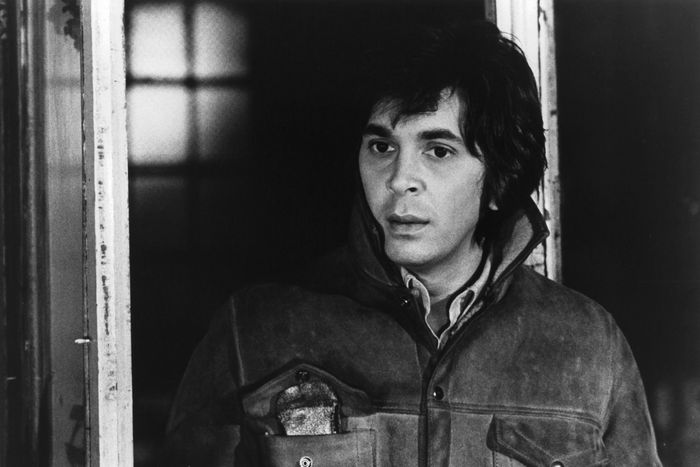

Langella had a natural command of the stage and, directors quickly noted, a fierce work ethic, arriving off book not just at first rehearsal but even at auditions. With his piercing dark eyes, the cheekbones of a Vogue cover girl, and sleek black hair, he landed several leading roles Off Broadway in quick succession. “I was very aware that Frank was already on the rise,” recalls the actor René Auberjonois, who worked with him in the early days of the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center. “His desire to create himself as the kind of leading man that he wanted to be, and be recognized — well, he had a very strong competitive streak.”

That early success led to starring roles in two 1970 films: Mel Brooks’s The Twelve Chairs and Frank Perry’s Diary of a Mad Housewife, in which he played an icy Lothario. Onstage, Langella seemed to have a rippling cloak of pheromones, but it didn’t translate to the screen, and his Hollywood career foundered. In 1977 he landed the title role in Dracula on Broadway, earning $30,000 a week.

“Frank was stunningly sexy,” recalls Elizabeth I. McCann, one of the show’s lead producers. “He played it with great gusto and great wit and great style. He had it nailed. To me there would never be another Dracula.”

The exposure and renown encouraged his growing sexual adventurism in a no-holds-barred era. In the theater, he shifted easily between the classics and contemporary plays; his private life life swung between extremes as well, though less gracefully. When I mentioned to one of Langella’s closest friends that he was ready to discuss his affairs with men as well as women and his destructive sexual addiction, he nodded in recognition. “When we went through the entire era of the AIDS epidemic,” the friend told me, “I was very blunt with Frank,” telling the actor that “you may not be able to be helped if you’re not gonna protect yourself.” As is true of any addict, the pursuit of his drug — in his case, sex — took precedence over everything else, including work.

It wasn’t until 1993, when Ivan Reitman cast him in his political comedy Dave as a scheming White House chief of staff, that he started to find his place in Hollywood. “Dave was a defining role for me,” Langella told me. “I hadn’t been seen onscreen for a while and I had begun to lose my hair. I was 20 or 30 pounds heavier.” The matinee idol was now playing the heavy. While Langella continued to earn Tony awards for his dazzling stage work, Hollywood wanted him as a character actor, and he was happy to go along for the ride.

“I’m perfectly willing to accept the [charges of] narcissism, the vanity, the desire to be center, to rule,” he says. “What I will not accept is the rap that I did it for: Outta my way” — that is, ambition for its own sake or at the expense of others. But, he says, “I do have self-valuation. Whenever I get an award, I think of all that I haven’t achieved.”

Langella’s late-career revival includes scene-owning turns in the films Robot & Frank, Starting Out in the Evening, and All the Way, as well as the recurring role of Soviet-era spy handler Gabriel in The Americans. He also played King Lear, in a performance that left both British and American critics exhausting the superlatives. And yet, since winning that fourth Tony in 2016 for his heartbreaking performance as a combative man receding into dementia in The Father, he hasn’t been offered work.

Not until Kidding, and this stolid character, Seb.

The series begins as Jeff’s inextinguishable good nature and belief in the efficacy of noble intentions have begun to dissolve in the acid bath of a family tragedy. His wife (Archer’s and Arrested Development’s Judy Greer) is divorcing him. Their pubescent son (Cole Allen) is spiraling into a drug haze. Jeff’s sister (Catherine Keener), who creates the puppets for the show, has her own marital issues.

And then there’s Seb. “I was writing it for Jason Robards, but it turned out he’s deceased, and Frank Langella was the next best great thing,” Dave Holstein tells me from his car. It’s hard to tell if he’s joking. “Jim [Carrey] immediately wanted him. He brings such a gravitas and seriousness to all of our most absurd moments in the show. I just wanted to write big, Tony-nominated speeches for him.”

That proved irresistible to an unemployed actor of Langella’s stature, and it came after a long and frustrating period when he’d poured his heart into a stage revival of Arthur Kopit’s 1962 farce, Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad. A year earlier, in a workshop in Times Square, I’d watched as all six-foot-four of him, in pearls and lipstick, his voice pitched high but not too high as Madame Rosepettle, entered, savaging the winded bellhops arranging her luggage in a hotel room as her stuttering son watched.

Kopit had been eager to see his long-forgotten play resurrected with Langella as Mme. Rosepettle. “Frank wanted to do it, and what he thought about how to do it was exactly right,” he says. “He understood how it was about terror, and how Madame Rosepettle was scared. He understood something about it that I thought was absolutely real.” But it was not to be. At the workshop production, I watched as the invited guests squirmed, declining to engage. No producer ever came forward to mount a full production. The project was shelved.

Was this a failure? I didn’t think so. It was the perfect illustration of the qualities that have set Langella apart from so many of his colleagues. True to form, he’d made the dangerous choice, following where instinct led him.

Which is why I hold my tongue when Langella asks me about Kidding. The artists involved are interesting and the money is great. Bee stings? Constipation? I figure he’ll find a way to make it work. A few days later, he writes:

Jeremy,

All good on KIDDING. I prevailed with a reasonable and sensible proposal that makes the character much more palatable to play and the rewrites came swiftly and satisfyingly.

I leave for LA Sunday.

Shortly after that, he tells me he’s decided not to move forward with the biography, though, that he “must” tell his story in his own voice. I heard nothing more from him during the months of filming Kidding, during which time it’s also announced that the title role in the film of The Father is to be played by Anthony Hopkins. Showtime declines to make Carrey, or any of the principals involved, available for this story.

A few days ago, I emailed him about setting up a time to discuss the new show.

Jeremy,

It was a long four months in LA. I am planning on a respite from anything show biz for the rest of the summer and therefore must decline your request for an interview.

I hope you are well.

All Best,

Frank

With a bit of trepidation, I open the advance screeners of Kidding. King Lear he isn’t, but it looks and sounds like the great Langella. Sure, the bee stings are there, and the dabs of Calamine lotion. So is the gravitas. The poop line is gone.