And suddenly, Peter Bogdanovich is everywhere. The legendary director of The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon has just made a new documentary about Buster Keaton — The Great Buster: A Celebration — which will be premiering at the Quad Cinema in New York next week. A retrospective of Bogdanovich’s films, including many of his director’s cuts, starts at that same theater today. (A Keaton retrospective will follow a week later.) Meanwhile, the director is one of the stars of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind, which was left unfinished at the time of Welles’s death and which Bogdanovich actually helped complete. His relationship with Welles is also one of the key subjects of They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, Morgan Neville’s documentary about the making of The Other Side of the Wind. Both titles are screening at the New York Film Festival this weekend, ahead of their November Netflix releases. So, it seemed like a good time to talk to Bogdanovich.

Our conversation touched on Buster Keaton, what makes a good comedy, his difficulties with producers, and his contentious relationship with the late Burt Reynolds.

Your Buster Keaton documentary has a somewhat unorthodox structure. You go through Keaton’s life, but then you double back, and in the last section of the film, you dig deeper into the decade when he did his greatest work.

There’s an old showbiz maxim: “Always leave them laughing.” I didn’t want to end with the diminishing returns of Buster’s later decades. I felt the audience would be much happier with getting to the great stuff at the end, so the last third of the movie or so is devoted to the features. I had that idea fairly early on, before I started making the movie. And when I learned that the Venice Film Festival celebrated him the year before he died, and that he received the longest standing ovation in the history of the festival, I guess that’s when it all fell into place.

How well did you know his life story before you started working on this film?

I had read his autobiography, My Wonderful World of Slapstick, and I saw the Keaton films when I was young. My father, who was a good deal older than my mother, had basically grown up with silent films; sound didn’t arrive until he was 30 years old. So he took me to see silent pictures at MoMA when I was 5 or 6 years old. But one of my everlasting regrets is that I didn’t meet Buster. I could have, but I waited too long. We lived very close to each other, I found out when he died. I was just about to start tracking him down.

You made one of the all-time great comedies with What’s Up, Doc? And while other films you’ve done have had comedic elements, you never quite returned to that style of very broad, screwball comedy. Do you sometimes wish you had?

Once I had done it, I figured I didn’t need to do it again. But I have made a few comedies. I think Paper Moon is a comedy-drama. What’s Up, Doc? was the most severe comedy, but my favorite film of my own is They All Laughed, which is a kind of bittersweet comedy. It was made tragic because of Dorothy [Stratten]’s death, but it was conceived as a romantic comedy. [In 1980, Stratten, Bogdanovich’s girlfriend and star, was murdered by her estranged husband, which Bogdanovich wrote about in his 1984 book The Killing of the Unicorn.] I’ve done it on the stage, too. One of my biggest successes on Summer Stage was a comedy called Once in a Lifetime by Kaufman and Hart.

Is there a secret to constructing a great comedic set piece?

Comedy has to be built carefully. I interviewed people like Leo McCarey and Frank Capra, and got to be friendly with a number of people like Howard Hawks, who made great comedies. And one of the things I learned was that you have to pay things off — this idea of three laughs and then a topper. An obvious examples of that in Doc is the scene with the pane of glass — not so much the glass itself, although that’s a very big joke, but the scene with the cars crashing into that parked van. The topper is the guy runs out and the whole van falls over. The chase was inspired by Buster Keaton at the time. He didn’t actually do a lot of chases, but his dynamic inspired me.

Another example in my pictures is [in] Paper Moon. We were finishing the picture and we didn’t have an ending. The one in the script I didn’t like, and I didn’t like the end of the book either. Then I remembered what I’d been told by McCarey and others about paying things off. It struck me suddenly that as we were about to leave Kansas and move to Missouri, we hadn’t paid off the $200: “You still owe me $200!” We had started with that at the beginning of the picture. That’s where I got the idea that she runs off after him. I also realized that we hadn’t paid off the photograph of her with the cardboard moon. And we hadn’t paid off the brakes on the truck being defective. So put all that together — and that was my ending.

That sounds not unlike Buster Keaton’s method of shooting his films without a finished script. Do you like that approach?

They never had a script on some films. They had a good beginning, good ending, and they said the middle would take care of itself. I’ve done a bunch of pictures where I didn’t have a complete script when we started. They All Laughed, Saint Jack, most of those films we were rewriting as we got to know the picture better. I liked doing it. It was a little dangerous, but luckily, I had producers that didn’t bother me.

Speaking of producers who bothered you: There are a lot of director’s cuts in the line-up of your Quad retro.

I wanted them to show the director’s cuts; I didn’t want to run the other versions. One problem is that Texasville is not available in the director’s cut except on a laserdisc, which they weren’t going to show. I’m trying to get the Criterion Collection to let me put together the director’s cut of Texasville, which is better in the sense that it’s a lot sadder. Because there’s 25 minutes missing [from the release version]. I wanted to reissue The Last Picture Show in theaters before we released the new film. The head of the studio when we were preparing to make the picture was Peter Guber, and he said, “Fine.” While we were shooting, Frank Price replaced him. Frank Price did not like me, and I did not like him, because he had already fucked up Mask, and I had fought with him on that. He didn’t want to reissue The Last Picture Show. He referred to that as “cheating.” I thought that was the stupidest thing I’d ever heard. And the movie wasn’t available at the time. So we cut a lot of the sadder parts that referred back to the earlier film — because audiences wouldn’t have had a chance to see it — and that left it more of a comedy.

What happened on Mask?

Mask wasn’t the version that I wanted when it was originally released. It made money, but it would have made a lot more money. My version was a lot less depressing — tragic, but a lot less depressing. I had to wait 20 years to get that right. The music was supposed to be by Bruce Springsteen, and there [were] 10 minutes that were cut out, too. Later, Bruce gave me the music for nothing, and because of that the studio was willing to spend the money to fix it up. So, the version that came out on DVD was the one I wanted.

It’s not just artistic differences. Usually, it’s ego, and power struggles and all that testosterone-fueled bullshit. [The Frank Price regime at MCA/Universal] was a terrible regime. There were political reasons why he didn’t want my cut. They hadn’t set the movie up. The picture they were pushing was Out of Africa, which was relentlessly boring, I thought. [Laughs.]

Let’s talk about The Other Side of the Wind, which you helped complete. In an interview we did years ago, you told me that Orson Welles’s vision was so unique that it was very hard for anyone to share it. So was it a challenge to try and cut together his footage the way he would have wanted it?

Yeah, of course. But on the other hand, he left enough examples of what he had in mind that we could follow [those] as a road map. It wasn’t easy. The script was pretty clear, but he rewrote it constantly. The fact that [producer] Frank Marshall was on the film for almost all of it helped a lot. I was on the film for part of it. And we had a very good editor, Bob Murawski. Orson had asked me suddenly one afternoon if I would finish the film if anything happened to him. I said, “Orson, nothing’s gonna happen to you!” He said, “I know, I know, but if it does, promise me.” So, when he died, I felt I had to keep my promise. We tried for years to get somebody to back us. In fact, Showtime agreed to do it three different times, but we couldn’t get the rights cleared. People who owned various rights were being very difficult. [Producer] Filip Jan Rymsza cleared up the rights holders situation by going and meeting with everybody — Patty [Welles], Oja Kodar, etc. — and then Netflix stepped up [to] the plate and really finished it. We even went over budget and they didn’t complain. They were very supportive.

It was pretty strange for me. I hadn’t seen any of the dailies, and there I am in my 30s. I’m now in my 70s. It was weird seeing that for the first time. I thought, “What ever happened to that actor?” [Laughs.] I’m very pleased we finished it, and I think Orson would be pleased, too. The only thing we had to add was the opening monologue setting up the picture. He wrote it, but he never recorded it. Frank Marshall said to me, “Why don’t you do it?” I said, “I don’t think I could do it as Peter Bogdanovich, but I could do it as the actor.” So that’s when we had the idea of having Brooks Otterlake [Bogdanovich’s character in the film] do it, and to have him say he didn’t really want the picture shown for so many years because he didn’t like the way he came off — which gave us a way of getting around why it was set in the ‘70s. I thought that was valid — because I don’t think Brooks would have liked the way he came off in the picture.

In They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, the documentary about the making of The Other Side of the Wind, it’s noted that you and Welles had a falling-out in the 1970s, after he and Burt Reynolds mocked you as they yukked it up on The Tonight Show.

Orson and I made up before he died. We spoke about two or three weeks before he died, and everything was fine between us. We loved each other, but things got in the way. I felt a bit betrayed by him about Saint Jack, because he didn’t do what I’d asked for him to do. That drove us apart.

Did you ever make up with Burt Reynolds?

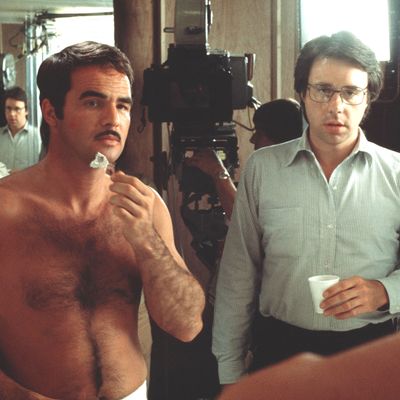

We never had a falling out, really. I didn’t see Burt at all after we finished shooting. He was a little nasty about me in his autobiography. I liked Burt, but he was a bit of a shit. He blew with the wind. He very much followed the box office. He was very affected by how people were talking about his films. He wasn’t a great friend, but he did two of his best pictures with me [Nickelodeon and At Long Last Love], and he worked hard. They were two of his best performances, but they weren’t successful, so he turned against them. Later, when he was looking to get an Oscar, he called me and said, “You stretched us, Peter.” I said, “You stretched well.” I remember one moment in Nickelodeon, where he did something with a rifle. And I said, “That was a bit Burt Reynolds, wasn’t it?” He looked like he was going to hit me. But he did it differently in the end.

In the Buster Keaton documentary you cite Gore Vidal’s line about the “United States of Amnesia,” when discussing how Keaton was forgotten for many years. Do you feel our appreciation for cinema’s past is getting worse?

Yes, there’s very little film culture in this country. There was more of it in the ‘60s. Younger directors seem to care a lot less about older pictures. You talk to younger kids about silent movies and tfhey look at you like you’re talking about Sanskrit. Same with black and white— they hate it. The first 30 years of talking pictures were dominated by directors who had grown up making silent pictures. Hitchcock, McCarey, Hawks, [John] Ford — they all started in silents. They knew that telling the stories visually was the art. Some of them dealt with sound better than others; Hawks incorporated sound very easily, but it took Ford a while longer. You can see in those films of the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s that the primacy of the image is still key. That’s being lost.