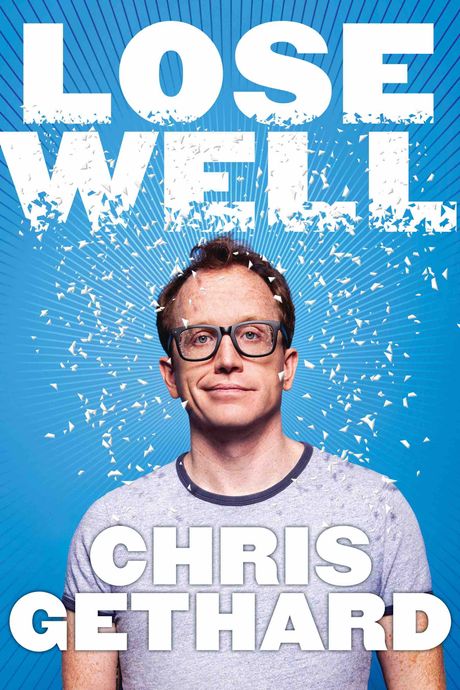

Chris Gethard is one of the most innovative and delightfully weird voices in comedy today, thanks in part to his stage–turned–cable access–turned–television series, The Chris Gethard Show. In his new memoir/self-help book Lose Well, he discusses the many necessary failures, false starts, and bad decisions that ultimately led him to where he ended up (and belonged).

Early in my comedy career, I’d get a weird idea every now and again that made me giggle with maniacal glee. I was doing tons of improv, and more and more storytelling—very traditional stuff. But, at the same time, I kept getting these odd impulses. It was fun to see them through to fruition.

In one of the earliest, I held a tournament where two comedians would each get five minutes to make a crowd laugh. A panel of judges sat in the front row. Whomever they deemed the winner moved on. The other person was shot, without mercy, with a paintball gun wielded by my friend Eli, a very good person who was able to turn off his morals to do this job. This show sold out. People around town talked about it. Instead of doing it again, I went back to the more basic stuff. Don’t do that again, I told myself. Wouldn’t want to get a reputation as some oddball.

About a year later, I staged a storytelling show where everyone was required to tell stories of pooping their pants. Instead of the traditional microphone stand or podium you might find at a storytelling show, I placed a toilet center stage. Everyone was required to pull down their pants and sit on the toilet while telling a crowd about times they shat themselves. It was also massively popular. And yet again, instead of harnessing the momentum this show offered, I let my own self-consciousness lead me right back to the traditional forms of comedy that weren’t half as exciting.

I took great joy in staging a conversation at Peter McManus, a bar in Chelsea comedians love to visit. “What other comedian do you think you could beat in a fistfight?” Comedians are competitive people. These harmless conversations got analyzed in back booths with great vigor. For about a month, this became a dominant topic of conversation in my community. People created their own ranking systems. “Rob Huebel and Rob Riggle are best friends. But who would win in a fucking street fight?” “Could Bobby Moynihan take out Jason Mantzoukas?”

I was proud I’d planted the seeds for these dumb hypotheticals, which everyone in my corner of the New York comedy world seemed to obsess over. Then, a moment of inspiration struck. A few other masochistic comedians and I rented a warehouse in Brooklyn. We set up four stanchions and connected them with police tape to make ropes for our makeshift ring. We hired a professional boxing referee. Six pairs of comedians faced off. Some of us took boxing lessons in the weeks leading up to the fights. Then, we fought.

The first fight quickly showed that this day would be taken seriously. Let’s just say we all learned not to fight John Gemberling. In real life, he is a warm, inviting guy, but in the ring he has a heart of stone and a jab that can draw blood.

We filmed the day’s proceedings. Everyone present at the warehouse agreed to keep the results under lock and key. We screened all six fights to a bloodthirsty sold-out crowd at the UCB Theatre. Paul Scheer took bets. I buzzed with energy. It was a thrilling night. But when I got home, I lay in my bed unable to sleep because I thought everyone was going to think all I could do well was weird stuff.

In 2009, a group of students at New York University took to my comedy. They showed up at every show I did. They sometimes wore homemade T-shirts with hand-drawn sketches of my face on them or phrases like geth busy living or geth busy dying. The whole thing was surreal, and I felt like a big part of it was that they knew a low-status schlub like me shouldn’t have a fan club.

But they were insistent that their affection was genuine. They started a Facebook group and one of them said, “I love Geth’s storytelling show. But I’d really love to go to all the places in New Jersey where they take place and see them there.”

It got under my skin. I felt like I was being made fun of. So I joined the group.

“I’m calling your bluff,” I said. “Rent a bus. We’ll do it.”

To my shock, they did. We did the math and realized to make this bus pay for itself, we had to charge forty dollars a ticket. That was an exorbitant price for young comedy fans in New York City who are used to their shows being priced at five bucks.

It sold out right away. I drove people to the actual locations of some of my most strange, grim experiences and told them the tales up close and personal. I even brought a group of sixty random people into the basement of the house I grew up in, which my family had sold eleven years prior. I stood near a wall, narrating events from my childhood.

“There used to be a couch here,” I informed them. “In 1997, I lost my virginity on this very spot.”

“Jesus Christ, come on, man,” said the owner of the house from the back of the room.

In 2009, I was feeling restless and wanted to mount some sort of new show. My sincere hope was to make something industry friendly. Something that people who have hiring power in the comedy world might see. Maybe I could get a staff writing job on one of the comedy shows that filmed in New York. SNL. The Daily Show. I just had to figure out how to make it clear that I could play ball by the terms of those productions. I hatched an idea: I’d always loved talk shows. Maybe I’d mount my own. I’d host it, I’d get friends to write and appear on it with me. By showing off my version of a talk show, I hoped I could put myself in a position to get a job with one someday.

The artistic director of the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, Anthony King, had other ideas. “I can’t stress how many people pitch me the idea of them hosting a talk show,” he told me. “Everyone has that idea.”

“I can see that,” I said. “But I’ve been around for years, and I think I could make one that’s really good.”

“I agree,” he responded. “But here’s the thing I don’t understand about you sometimes: Why do you want to put on a shirt and tie? Every asshole who puts on their own talk show in the comedy scene wears a suit, does a monologue with jokes about recent news, and interviews some semifamous friend they have onstage. Why would you of all people do that?”

“Because that’s what talk shows are,” I told him. “And I’d love to work on a talk show.”

“I’m going to give you a talk show,” he said. “But I’ll cancel it as soon as it looks like some cookie-cutter talk show.”

“I don’t understand,” I said.

“Dude, all your best ideas are fucking weird! No one else rents fucking buses. No one else can turn physical violence into a room of two hundred people having the most fun they’ve ever had. No one else can convince sixteen other comedians to voluntarily get shot by a paintball gun when they bomb. For a few years now, I haven’t understood why you don’t just own that shit. People love those shows. That has to be your talk show. All your weird ideas. I’ll give you one slot a month, but it’s going to be the home for that part of your brain.”

“Jesus,” I said. “I never thought of it that way.”

This was very true. Every time I’d stage one of those weird shows, I’d put my guard up and clamor to do some regular stuff again. I didn’t want to be known as the guy with the superstrange ideas. It made me feel like everyone would see me as a total fucking weirdo.

But Anthony made me realize that My greatest asset is that I’m a total fucking weirdo.

People would bring the cool shows up to me after they were done. They were always enthusiastic. And I always found a way to apologize.

“Yeah, I don’t know why I do that dumb shit.”

“That one was fun, sure, but it’s not all I do.”

“I’m glad you dug that one. I’ve been doing a lot of stand-up lately too.”

My insecurity that my ideas were too odd led to tons of apologies. I sat in that chair across from Anthony and was flooded with thoughts. I spent so much time resisting the things that made me unique. I spent so much time doubting them. I strategized around them. I’d do a weird show that went well. I’d have another good idea, but I’d sit on it for a year to space it out. Even my writing packets for professional jobs had backward logic. I submitted a Saturday Night Live packet with a bunch of hip-hop sketches. This was while the Lonely Island was on the show and producing tons of great hip-hop-driven digital shorts. I figured I should show SNL that I could do what they did.

Why would they look to hire someone who can do what they already have? I never once submitted a packet that showed off the things that only I could do. I was doing some of the most unique stuff in New York comedy back then, and every writing packet I ever turned in reflected only bland ideas. I cost myself opportunities, money, and most important, a hell of a lot of time.

Instead of showing off my out-of-the-box impulses, I subconsciously created a habit of snuffing them out. I thought my weird ideas were a roadblock to a fruitful career. In reality, they were my greatest asset. And over and over again, my apologies murdered their potential.

There are things that only you can think of, because you are you and there is only one you on planet Earth. It makes sense that your most unique ideas feel terrifying, because they are creatively risky and also expose the inner workings of your brain. You have to learn to turn off the self-doubt about these ideas. They are the greatest currency you have. Until you learn to erase the self-doubt surrounding them, you will never truly be able to bet on yourself. It is impossible to commit fully to your passions when you can’t lower your own defense mechanisms and stop apologizing for them.

Anthony explained another eye-opening aspect of my situation, then gave me a directive that really changed things around for me.

“Do you know that people use your name as the benchmark for weird shit?” he asked me.

“Oh God,” I said. “What does that mean?”

“When people pitch me really bizarre stuff, they’ll say ‘It’s kinda like one of those Gethard shows, I guess.’”

I was confused.

“When people want to do cool, strange shit, they use your name as an adjective for it,” he explained to me. “But you’ve never gone all in on it. It’s time to do it.”

I nodded.

“One more thing,” he told me. “I’m not letting you hide from it this time. The only way I’m putting this show up is if you call it The Chris Gethard Show.”

Anthony really changed my life that day. It was yet another example of a true ally seeing things better from the outside and guiding me where I needed to go.

From Lose Well. Copyright © 2018 by Chris Gethard. Reprinted with permission by HarperOne, a division of HarperCollins Publishers.