I remember that afternoon vividly. It was Sunday, September 4, 1993, and the windows of my South London flat were wide open to let in the sultry late afternoon air as I sat staring at a pile of interview tapes on my desk. I wondered how on earth I was going to be able to compress 15 hours of interviews, recorded in Los Angeles the week before, into a short, 500-word “jokey” piece for Britain’s Mail on Sunday magazine.

It was not going to be an easy feat. Not least because my subject was the world’s most famous dwarf, French actor Hervé Villechaize, who had portrayed one of the greatest Bond villain henchmen of all time, the diminutive Nick Nack in 1975’s The Man With the Golden Gun. Hervé had gone on to achieve even greater worldwide fame as Tattoo, the cherubic, mischievous, white-suited helper to Ricardo Montalban’s Mr. Roarke on the hit TV show Fantasy Island. It was more than a decade since Hervé had been fired from the show in a blaze of publicity, but the magazine felt Hervé might add some color and “novelty value” to the upcoming issue. If all that came from it was an entertaining dinner-party story for my friends back home — who would all wonder, as I did, how such a surreal, Felliniesque figure could even be real — then fine by me. I certainly never for one moment considered the possibility that my meeting with Hervé, and its effects upon my life, would still be felt a quarter of a century later.

After all, it was meant to be a quick job. A few funny stories about working on the Bond movie and Fantasy Island, a couple of photos, some short jokes perhaps, and then I would move on to other, far more important interviews. The summer I met Hervé, I had interviewed a number of disparate and colorful characters from Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols to former British prime minister Ted Heath. Getting in the room with them, by comparison, had been a cakewalk. In retrospect, the surprisingly complex negotiations that preceded my meeting with Hervé were my first clue that something about this might turn out to be a little unusual.

First, there was an old-school L.A. publicist, then a near-deaf former agent, and then finally a manager who sounded drunk on the phone but who was able to give me the number of Hervé’s personal publicist, Kathy Self. After a lengthy chat, it turned out Kathy was also Hervé’s longtime girlfriend and protector. She said that Hervé might consider doing the interview, but would first like to read some samples of my work. Hervé had been “burned” numerous times by unscrupulous journalists who had misquoted him and only wanted to ensure this did not happen again.

It made sense, but by this point Hervé had been out of the limelight for so many years that he was, for most people, a distant cultural memory. Some might have even described him as a has-been. And yet here he was, auditioning me for the part of interviewer. My editors and I found it pretty hilarious, but the Howard Hughes act was more than a little intriguing.

Hervé and I agreed to meet at the now long-closed Café Moustache on the corner of Melrose and Crescent Heights in West Hollywood. Somewhat past its ’70s heyday, there were still signed photos of Lee Majors, Wolfman Jack, and Charo on the walls. In pride of place above the bar, there was one of Hervé himself, wearing his famous Fantasy Island suit, a large sack of fan mail at his feet.

The photographer I was working with, Sloane Pringle (not a stage name), had shown up early to prepare his lighting setup and we were ready to go long before the appointed hour of 3 p.m. By 4, Hervé had still not appeared and Kathy was not answering her phone. By 4:30, I told Sloane we had better pack up if we were going to make our next interview. “Fucking showbiz dwarfs, they’re all the same,” he snarled quietly. No great loss. We had bigger fish to fry.

As we were loading the equipment into the back of our rented Lincoln Town Car, from somewhere behind us came the loud screech of tires. A tattered white stretch limo lurched up to the valet stand and out popped Hervé, all smiles and breathlessness, offering profuse and sincere apologies for his “terrible, unacceptable” lateness. He was wearing a red Hawaiian shirt, the kind one might find at an airport kiosk, while surfer’s sunglasses crowned his tiny, swollen head. He was much older than I had imagined, his hair graying, his complexion jaundiced. It was like meeting a character from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita or a Buñuel film, or perhaps an envoy from some distant but parallel universe. But it was the voice that really got you. It was high-pitched and gravelly, like a baritone who’d inhaled helium.

I asked Hervé if something had happened to make him so late. “I was reading your articles. Zey only arrive zis morning.” He smiled charmingly and gestured us back inside the restaurant. He was so fascinating and charismatic that Sloane and I didn’t bat an eyelid and just followed him. I called the publicist of my next interviewee to say we were running a little behind.

The interview itself only lasted about half an hour — that’s all we had — but I was able to ask all the expected questions. How was Roger Moore to work with? How exaggerated were the stories of Hervé’s womanizing in Thailand while shooting the Bond movie? Was there truth to the fact that he and Ricardo Montalban had had problems on the Fantasy Island set?

Perched on his favorite chair like a king, Hervé answered everything with a mischievous warmth. It was impossible to tell whether he was actually telling the truth as he was in character, alternating between Tattoo and Nick Nack — or was it Hervé himself? He was constantly joking, continually sipping at a large glass of expensive red wine, occasionally stabbing at a gigantic plate of duck a l’orange with the lock knife he had earlier pulled from his waistband with a dramatic flourish.

It was great theater, but there was something else about Hervé beyond the otherworldliness, beyond the meta-fantastical nature of just being in his presence — something very vulnerable, very human. You couldn’t help but like him, love him even. He so enjoyed telling his stories, and no doubt so rarely had an audience for them these days, that his enthusiasm and rapacious charm quickly became infectious. I remember thinking that Hervé was without a doubt the most singularly original and entertaining person I had ever met. It was a shame I had to leave so soon.

As I clicked off my tape recorder to indicate that the interview was over, Hervé’s face flashed with anger. Clearly, he was just getting warmed up, but Sloane was already in the car and we were late enough as it was. As I looked down to pack away my notes and tape recorder, I could sense rapid movement out of the corner of my eye. By the time I looked up again, Hervé was standing right next to me, perhaps only three feet from my face, the blade of his lock knife pointed at my throat.

I laughed intuitively — how could you not? I was about to be shivved to death by the dwarf from Fantasy Island — but the look in Hervé’s eyes was no joke.

“Now I’ve told you all ze bullshit stories, what about ze truth?”

“What do you mean?” I asked as casually as I could.

“Would you like to hear ze real story of my life?”

I could see that Hervé wasn’t truly threatening me, that all he wanted was my attention. And now he had it. He let out a small smile of relief. “Meet me tomorrow night at Le Petit Chateau in Universal City. 8 p.m.” I gestured down at the blade. It was still far too close for comfort. Hervé finally let it drop, paused, and then took a small bow. Without doubt, this had been an impressive coup de théâtre, and I was certainly more intrigued than ever, but now I only had one question: What the fuck was going on?

A long interview and photo session with a young actor from a popular TV show had been scheduled for the next day, but it was hard to generate much enthusiasm as I couldn’t stop thinking about Hervé and our dinner. As soon as the interview was over, I rushed back to the Hyatt, jumped in the shower, and then took a yellow cab to Universal City. At first, Le Petit Chateau seemed abandoned but then I spotted Hervé, right at the back of the cavernous white dining room. He was sitting at a large round table under a spotlight. Julie London’s “Fly Me to the Moon” played softly in the background. The show had begun early tonight.

As I sat, I noticed Hervé had several glasses of wine and brandy set out in front of him. There were several plates of food too — classic, rich French dishes that he would expertly pick at with his little lock-knife throughout the evening, in a not-so-subtle effort perhaps to remind me of the night before. I pulled out my tape recorder and placed it in front of him. “So what about this ‘real story’ of yours, then?”

Hervé gestured to the plates of barely touched food and laughed. “Aren’t you going to ask me why I only taste things first?” Sure, I nodded. He said his doctors had told him that because of his severe gastroenteritis, it was only safe to sample them. He demonstrated by delicately slicing off a tiny tranche of steak and dropping it on his tongue. He added that the worst offenders were cigars, rich chocolates, and Roquefort cheese. And with that, Hervé smiled and lit a Monte Cristo.

He said his medical problems had stemmed from having “the head of an old man but the internal organs of a child.” He weighed just 63 pounds and only one of his lungs functioned, worsening his respiratory problems. My eyes couldn’t help but find the cigar slightly shaking between his stubby fingers. It was at that point that I also noticed the green Samsonite vanity case, open on the chair beside him. Inside, there were dozens of bottles of various medications and painkillers on which he’d written things like “strong” or “extra care.” As I glimpsed a dangerous-looking hunting knife among the bottles, Hervé snapped the case shut.

Seemingly out of nowhere, Hervé produced his own tape recorder, turned it on, and placed it next to mine. “I don’t like to be misquoted,” he explained with a shrug. Then he took a long raspy breath and for the next several hours, proceeded to tell me almost everything notable that had happened in his life.

Hervé was born in Paris in April 1943, the second eldest of four sons; his French father was an eminent surgeon, his mother a well-to-do Anglo-Italian socialite who drove ambulances during the war. He was the first dwarf in the family’s history, a fact he attributed to his heavily pregnant mother’s fall in a field as she fled from German artillery fire. His mother had been devastated by the news of Hervé’s dwarfism and he had been confined to the attic of the Villechaize home when guests were around, until the age of 7, when a prodigious natural talent for art had been discovered. But still, he said, he knew in his heart that his mother loved him very much.

Hervé’s childhood had been grueling. His early memories were nearly all of protracted and painful medical treatments. “I started realizing I was different when I went from hospital to hospital. I was 5 or 6 when I became conscious of it. At the time, you have to understand, dwarfism was something they did not know too much about. My father, being a doctor, made it his duty to make sure that I had the best medical care. They would try everything to make me grow.”

At age 7, Hervé went to Germany with his father to undergo a series of experimental treatments that verged on the barbaric. They failed, and after another round of treatments at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital, he was sent to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota on his own at age 11. After a year, he was “so sick of hospital wards and being prodded by needles” that he begged his father to let him come home. “One time, they cut my throat from ear to ear to look at my thyroid. I will always remember that. The waking up, the stitches, the crying, the nun praying in the corner. They put clips in my throat so I could eat. It was a harrowing experience.” None of the treatments worked. “After each one, I grew a little bit, a little bit, but in the end it made no difference.”

As horrible as all of this was, Hervé found cathartic respite in painting. There he was able to express the endless love in his heart as well as the darkest torments of his soul. He felt he was destined to become an artist and began realizing ambitions to pursue a career as one by studying at the prestigious Les Beaux Arts and La Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse. He held two major exhibitions before he was 18 and won a first prize in a City of Paris art competition. Hervé proudly told me he’d been the youngest painter ever to have his work exhibited in the Museum of Paris.

But life in the Paris of the ’50s and early ’60s was far from easy for someone like Hervé. On several occasions, he had been randomly attacked while walking down the street by strangers who called him “wrong,” or “a mistake.” He was beaten severely more than once, so at age 21, at his father’s suggestion, Hervé headed to America to escape the almost medieval intolerance toward dwarfs that was prevalent throughout Europe at the time. “My father told me, I don’t think you should come back until you are successful,” he said.

Hervé arrived in New York in 1964 with plans to gain an art scholarship. While that failed to materialize, he managed to teach himself English by watching cowboy films while staying at the Park Savoy Hotel, a seedy gangster hangout. He soon rented an apartment on 57th Street and embraced New York’s burgeoning avant-garde theater scene, wearing a kaftan and working with the then-unknown Sam Shepard. “I was the littlest hippie in the [Greenwich] Village,” he told me. But still, Hervé carried a knife under his clothes at all times, a habit he never grew out of. He was determined never again to come out second-best in a street fight.

Hervé graduated to films in 1968 with a part in Mad Storm, an experimental film by Norman Mailer, and Seizure, Oliver Stone’s first feature. More offbeat parts followed, including a “small” role in The Gang with Robert De Niro, until his cinematic peak six years later, when he earned $20,000 playing Nick Nack alongside Roger Moore in The Man With the Golden Gun.

Hervé told me adored the Bond actor, with whom he shared a similar taste for practical jokes. “Roger would get the concierge to phone my hotel suite all the time and say there is a lovely girl waiting for you in the lobby,” he recalled. “Every time I go down the stairway and nobody came. That happened every day.” On location in Thailand and Burma, Hervé’s predilection for the local women was legendary. When filming ended, Moore returned his joke gift of penicillin with a note saying, “I think you probably need this more than I do.” Even two-time Bond girl Maud Adams found herself the target of Hervé’s relentless attentions. At a rowdy cast and crew dinner in Bangkok, he loudly invited her up to his room to demonstrate how a “magical French dwarf makes love to a beautiful American woman.” Without skipping a beat, Adams apparently wagged her finger and quipped, “Now, if I find out you’ve done that, I’m going to be very, very upset.”

Not surprisingly, given his approach to romance, Hervé’s eight-year marriage to Anne, a New York painter, ended in 1976. “I am not a womanizer,” he protested. “I just love women. All women …”

Hervé smiled at that, then paused to take a large gulp of brandy. He threw some bills on the table and grabbed his green Samsonite Vanity case. “Now, why don’t we get out of this dump and go have some fun?” He was gone before I could even answer.

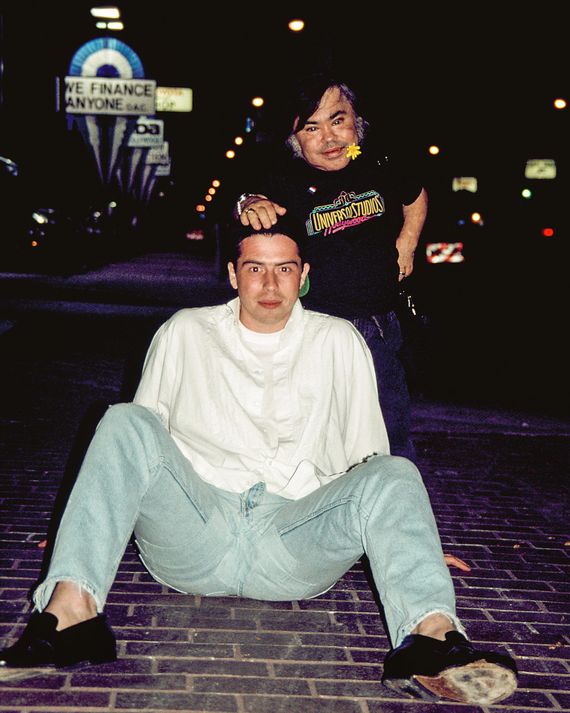

I packed away my things and came outside to find Hervé posing for a photo with the valets. As he signed an autograph for one of their kids, someone screamed, “The Plane! The Plane!” from a passing car. Hervé saluted his new admirers and gestured for the waiting white limo to pull forward. He opened the door himself, threw in the vanity case and clambered inside after it. After a moment, Hervé reappeared at the window with some kind of tropical flower in his hair. He waved a wad of dollar bills at me, gesturing for me to join him in the car. “Have you heard of Jumbo’s Clown Room?” I shook my head, no. “Hurry up, English!” I hesitated briefly, looked back around at all the valets staring at me, and got inside. What else was I going to do?

If you want to see what happened next and take a ride with Hervé in the white limo, tune in to the film I have made about my strange encounter. My Dinner With Hervé airs October 20 on HBO.