“Making a movie is a powerful thing,” says Adam Driver, dressed in a baggy hoodie and eating a breakfast of bacon and eggs at Brooklyn’s Dumbo House. “And to fuck it up or get tired while you’re making it?” He frowns. “Why not make sure you leave nothing on the table instead?” The 34-year-old actor is here on a cool fall morning talking about his own career, both onscreen — most recently in BlacKkKlansman; most famously as Adam Sackler in HBO’s landmark Girls and Kylo Ren in two Star Wars films — and onstage. It’s the latter, via his Arts in the Armed Forces nonprofit, which brings theater to military personnel, that he’s most eager to talk about. (On November 12, AITAF will celebrate its tenth anniversary with a special Broadway performance of Sam Shepard’s True West.) But he knows it’s the glow from the big and small screens that often draws people in. Like, presumably, the eager young podcaster who sidles up to us and asks if Driver will participate in a live podcast something or other. Or the barista who wants his autograph in her book of poetry. “I thought,” Driver says, despite having handled the interruptions gracefully, “that here I could avoid that kind of thing.”

Stories written about you always make a big deal out of the fact that you’re an actor who served in the military.

Like it’s a kitschy thing?

Not so much kitschy, but as if those two jobs are fundamentally at odds. Are they?

I see more commonalities than differences, but yeah, in one job you’re pretending the stakes are life and death and in the other they actually are. And people expect that being in the military is going to be difficult. They’re not like, “Oh, the catering’s bad. Oh, we’re shooting more than 14 hours?” Fucking who cares? The stakes are so high [in the military] that there’s no “Well, I feel this way.” Everyone is on the same plane.

What are the commonalities?

The team effort. You have a group of people working toward a bigger picture, working together intimately for however long it takes to get the job done, and there’s somebody who’s in charge who, if they know what they’re doing, makes everything seem necessary and urgent. And if they don’t know, everything feels like a demoralizing waste of time.

But the collective effort you just described could also be said about a business or a sports team.

Sure.

So what I’m trying to ask about are the specific mental and emotional similarities and differences that might exist between actors and soldiers. It seems to me that one profession is at least partly about individual expression and one is more about conformity. Do you know what I mean?

Yeah, I do. This is where things differ: In the military there’s a structure in place for how things work, and you can’t supersede it. If a PFC is really good at his job, then he’ll get put in charge. But in making movies, when people get to a certain level they can push their needs ahead of others’. Acting is not set up to be a collective effort. It can be, but it never is.

What do you mean?

There’s more bureaucracy to navigate.

There’s more bureaucracy in acting than in the military?

I’d never realized that most of your job in acting is managing personalities and talking about your job. Only, like, 10 percent is the actual doing of it. Sometimes that 10 percent is all you need to keep motivated but often there’s so much bullshit — never mind. I don’t want to complain about having a great job. I don’t want to be that guy. What am I trying to say? Obviously in the arts people have more liberty to be individual, but I still think of the work as a group effort. I’m not saying my view is better than anyone else’s but it can be at odds with someone who thinks, No, you guys are here to support me with my effort.

How much do money and fame distort your thinking and feeling about work?

Does money? Yeah, it does. In terms of this nonprofit, we [AITAF] could probably be doing even better financially if I wasn’t one of the people at the head because I’m so unwilling to do so many things — or talk to people in general.

Because those things make you uncomfortable?

I don’t want to start getting into favors. It’s not about me and Star Wars. It’s about the people that we’re trying to serve and if you don’t get that then I’d rather not be associated with your money. I guess that applies to acting also. But then you have someone like [John] Cassavetes, who did all this TV work and had no loyalty to the things he was doing just for money. He would take all that money and dump it into Faces or Opening Night. I’m sorry. I feel like I don’t have the right answers for you.

There’s nothing wrong with your answers. What made you think acting could fulfill you in the same ways that being in the military did?

I don’t know. As you change, your relationship to your job changes. At school [Juilliard] I learned the value of time. Well, I learned that in the military, but I transferred it into making movies. I don’t take doing a play or making a movie for granted: We’re here, right now, and we’re never going to get a chance to do this again. It always seems like a miracle when someone is willing to pay for us to do that. And the fact that films are so democratic — for me, it was discovering [Martin] Scorsese and [Jim] Jarmusch movies in Indiana.

The Blockbuster in your town had Jim Jarmusch movies?

It was a Hollywood Video. We also had a Blockbuster and PJ’s Video. You just learn how films have a way of finding their audience. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore was completely different from my life growing up, but finding it was so powerful. Making something that can affect someone like that is an amazing opportunity. And we’re not going to live forever, so we have to make the most of the time we have. I’m getting very saccharine, but you can’t take anything for granted. I don’t know, these big themes of life and death — feel free to jump in any time.

Okay, I know that acting in Silence, which was all about sacrifice and purpose, made you wonder about the larger point of being an actor.

Right.

So how does thinking about your job in a holistic way like that affect how you go about it?

I don’t know if I have a good answer to that.

I bet you do.

That thinking you just described affects everything. Without sounding pretentious, which is impossible, I’m trying to mean it as much as I can. So I want to work with people who are taking things seriously. There’s a quote I stole from an interview with Thelma Schoonmaker. It’s something like, “Making a movie is like having to take a piss.” It’s so urgent. That’s how I feel.

Does acting need to be difficult in order for you to feel like it’s worthwhile?

No. Some roles are more challenging than others. Silence, for example, was physically exhausting but that’s what was required. I do like to work hard, though. I don’t know if that’s because I’m from the Midwest and was raised with “you work from nine-to-five and you come home exhausted.” But I don’t need work to be any more difficult than it needs to be. I’m always trying to find a way to work more economically. Can I ask you something?

Yep.

Do you feel with writing that you overdo things or put a lot of work in you didn’t need? I always want to feel like I’ve exhausted every opportunity so that no question comes up while I’m working that I can’t answer.

I think what I do is a million times easier than what you do, but yeah, I try to make sure I’m as prepared and have as many cards to play as possible.

Right, right, right. Also, this is another frustrating thing: You’re at a table read and you’re reading the script for the first time and in a way it’ll never be that good again. You weren’t thinking about it. You weren’t overanalyzing. You were just doing what was instinctual. I’ve been lucky to work on jobs that required me to trust my instincts and move on. [Steven] Soderbergh is one of those people who will only give you one or two takes no matter how much you’ve prepared. Spike Lee is another. Then you have Noah Baumbach, who’ll do 50 takes and that’s 50 opportunities to do the same scene in a completely different way.

You did an interview with Noah Baumbach where you talked about having to “rebel” when you get too comfortable with your work. What does that mean?

It doesn’t mean not showing up to set or anything like that. But if Noah wants me to move over there [in a scene], I don’t want him or me to get too comfortable trusting that I will go over there. So if we’re doing a scene 40 or 50 times, I’ll need to do something to remind myself that it’s all supposed to be happening for the first time. Maybe I won’t go over there and I’ll completely fuck it up. I’ll have a little battle with him [Baumbach] to keep the scene on its toes.

Are you someone who thinks a lot about your own thoughts?

You can probably tell from this conversation that I overthink the shit out of everything. I do try to be introspective but not to a point that it’s vain and I’m thinking me, me, me.

Let me tell you why my belly button is so interesting.

[Laughs.] Yeah, what makes me tick? In life I have such a problem of wanting control, and between “action” and “take” is the only time when I have to think about just one thing. In that moment there’s nothing else, and so much of my life I spend thinking about myself or other people, life, death, what our point is in the world. So to not have to think — this discussion is getting too abstract. I’m also moved by straightforward things like the writing in Ordinary People. You know that movie?

For sure.

There’s this scene in the hallway when he [Timothy Hutton’s character] is like, “You took trig?” And she [Mary Tyler Moore’s character] goes, “Did I take trig?” It’s very beautiful. There’s also a scene where those two are outside and he’s trying to talk about Bucky, the brother who died, and she’s talking about something else and he starts barking like a dog. So there’s the formal structure of the script — the lines that are spoken — and then there’s something abstract, too. I want to make sure that I don’t shut myself off from that abstract thing.

You’ve been helping run a nonprofit for ten years. What are you doing better now with it than you used to?

I didn’t used to feel comfortable fundraising. Like, “Yeah we’re interested in your mission but could you take a picture with my daughter? She’s a big Star Wars fan and if you do that I’ll give you $100,000.” No, I’m not going to take it. Is there nobody that is just philanthropic for the sake of it? Is there always some picture with your kid? I don’t want AITAF things to turn into Star Wars events. But then you say, “No,” and you’ve pissed somebody off. I don’t know that I ever handled that badly; I just took it too personally.

So now you say yes?

I still say no. It has to be the right thing or it can feel disgusting. Some people are good with being like, “It feels uncomfortable but imagine what you can do with that money.” So I’m starting to get more comfortable with that idea because we’re raising money not only for a military nonprofit, but a performing arts nonprofit. It’s difficult. We’re not saying, “Give us $100 and it’ll go towards $100 of art.” We’re giving something that you can’t quantify.

You find that you can’t emotionally disassociate when you have to glad-hand? Even if you know it’s for a greater goal?

I can see the advantage of going “What do I care?” but I’m not wired that way. This is an ongoing thing I’m trying to figure out. Sometimes I feel like I’m doing us [AITAF] a disservice, but I don’t want people to give us money for me. I want to cultivate donors that we’ll have a lasting relationship with. So it’s not just, “Give me a check and we’ll keep this as impersonal as possible.” I’m trying to make things meaningful. Do you know what I’m saying? I’m not quite explaining myself.

I get what you’re saying.

Okay, good. I’m trying to say things to you here that I don’t normally say.

I know fame, and the subject of fame, is not your favorite thing. So how did that distaste factor into your decision to be in Star Wars? You had to know that’d kick things into a higher gear.

No.

No?

I was aware that more people would see it than see most things I do, but I don’t think I could have anticipated how often I’d get recognized because it’s so different for every person. I’m very tall and I look a certain way. I can’t blend into a crowd.

You’re fairly nondescript this morning.

I look suspicious.

What’s interesting to you about playing Kylo Ren?

That’s hard to say because we’re working toward something in particular with that character. I don’t want to give anything away.

It seems like it’d be fun to play around in that world.

Yeah, the scale and size is interesting. Usually you work with people who are like, “Everybody save their cigarettes because we’ll need them for the rest of the movie.” But Star Wars has 4,000 people working on it. It’s an entirely different process.

Is there anything about your public persona that’s given you insight about yourself? Or made you think about yourself differently?

What do you mean?

There are very few people in the world who can see the ways in which a large number of other people view them. But celebrities can. So does seeing what people pick up on — whether it’s being considered attractive or intense — incur any particular self-reflection?

Being an “intense” actor, I don’t understand what that means. That I show up on set and glare at people? That before every scene I’m like, “I need to fire off a rocket really quick and then I’ll come back and act.” That I carry around cold cuts that I smash before every scene?

Do you?

[Laughs.] Only on Paterson. I don’t think of myself as an intense person. If what I’m doing is so abnormal that it’s intense — yeah, I have no idea. I’m not a method actor. I like to stay focused on set but it’s not because I have a process that I’m imposing on everybody else. Sometimes you have to be more focused in between scenes because what’s happening is that, on something like Star Wars, it’s pure comedy in between takes. It’s stormtroopers running into walls because they can’t see through their helmets. So I don’t know where the intense thing came from.

This has been a mostly serious conversation. So just to counterbalance a bit: What do you do for fun?

What do I do for fun?

Assuming you have any.

I’m so fun that I can’t think of anything. Clubbing. I go clubbing.

Did I read somewhere that you play music?

No, I don’t play music.

You don’t play an instrument?

I play the piano, but it’s not …

It’s not for fun?

[Laughs.] Yeah, not for fun. Work is sometimes fun. I mean, I have fun. What do I do for fun though?

It’s okay if you don’t have an answer.

I have no fun.

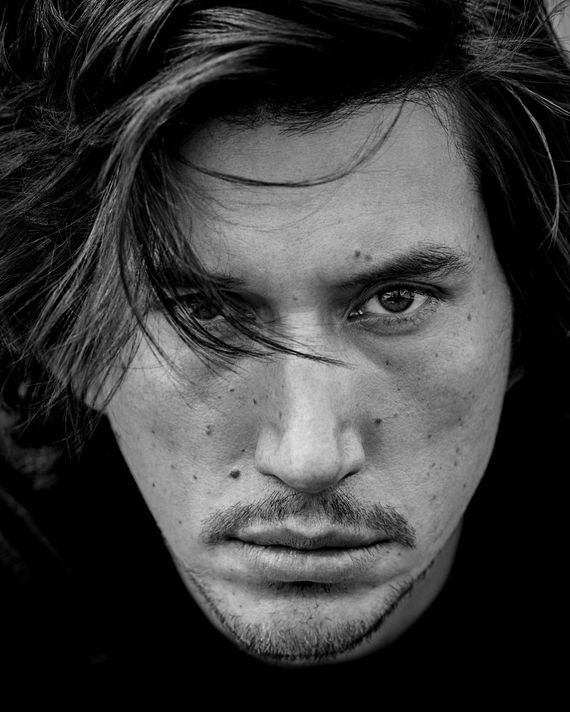

One more question related to fame, and I mean this as nicely as possible: I could imagine that in high school you were maybe kind of gawky looking, and then to learn as an adult that you’ve become an internet sex symbol — did that have any bearing on your self-conception?

I’m not aware of much of this. Social media, I don’t participate. I don’t have an opinion that it’s bad — or worse. You’re right that the existence of a public persona is an interesting thing, but I have no control over it so I don’t try to control it.

Some people try to control it.

That’s not how I want to spend my time.

When did you know that you wanted to be an actor? And when did being an actor feel like something that could actually happen?

In retrospect, I always wanted to be an actor. I did a play in my freshman year of high school and then tried to do theater throughout. The rule in our house was that I could do it if I got good grades. But being an actor didn’t seem like a realistic job to someone living in Mishawaka, Indiana. Juilliard was one of the only colleges I wanted to go to, and before I joined the military I auditioned. I liked that that school didn’t check grades and admission was based on your abilities. That doesn’t mean I thought good, I’m in.

It meant you thought you had a shot.

Yeah. And then I didn’t get in and I put acting out of my mind. But it wasn’t until I was in the military that I was like, “I know what I want to do when I get out.”

Was there something that happened?

I had a come-to-Jesus moment. There was a training accident with white phosphorous where we very easily could have died. After that happened I thought, The two things I really want to do are smoke cigarettes and be an actor. And then it just so happened that I did wind up getting accepted [into Juilliard] and I was incredibly lucky to go from having not even a novice’s understanding of the acting world to suddenly having the best access.

Is a soldier who has been affected by the arts different than one who hasn’t?

I think so. The Armed Forces has acronyms for acronyms but no language for expressing anything abstract. When you actually have that tool at your disposal, there’s such — I’m hesitating to say “cathartic” because that sounds pretentious, but there’s such power in being able to describe a feeling.

How does having that ability manifest itself in a soldier’s behavior?

Speaking for myself, coming from the military and not talking about what we did and then suddenly encountering a play that described my experience was incredibly important — even though the play wasn’t about the military. And the military is a stressful environment. Having an emotional outlet is — I hate to say therapeutic because I don’t want to label what we do as therapy — but I just think it’s good. And it’s not as if everyone in the military only thinks about the military. It’s like, you’re a writer and on top of writing you have to deal with your kids and whatever else is going on in your life. It’s the same situation with the military, only people are also handling weapons. People are stressed out. Expressing that feeling somehow makes it less stressful.

Do you remember the first play that was cathartic for you in that way?

True West was one of the plays that started it all for me: the idea of brotherhood, and how the characters are so different but bound by their brotherhood. I totally got that play. These answers I’ve been giving you are the worst. I’m listening to myself and thinking, What the fuck am I talking about?

Why do you keep saying that?! Your answers have all been fine. Anyway, this is probably overly broad, but I think that underneath a lot of what you’ve been talking about is the idea of integrity. Is the business you work in — show business, Hollywood, whatever you want to call it — a high-integrity one?

How do I give you an answer without giving you a headline?

I don’t know.

That was a joke.

I know. But I’m not bailing you out.

No, you aren’t. I would say no, it isn’t high integrity. There are people in this business that have integrity and I’ve been lucky enough to work with a lot of them. But overall no, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of integrity. I’m not saying anything controversial with that. At the higher levels there’s interest in money, and wherever that appears, it affects people’s choices. But I try to work with people whose main interest is in making the thing we’re working on as good as possible.

How interested are you in the subject of masculinity? Was exploring that part of what made the military appealing?

I don’t know if I was seeking that out — I guess so. When I was in high school I wasn’t an organized sports guy. A bunch of guys getting together doesn’t sound appealing to me. I never had the “hey bro, let’s all hang out” thing. I haven’t been asked about this subject a lot recently. When Girls came up I used to get these questions more.

Questions about masculinity?

About modern masculinity and what it means.

Why do you think people were asking you that?

Because I was playing a type of guy on that show. Maybe also because a lot of people thought that since Girls somehow represented a generation of women then that guy [Adam Sackler] also represented a generation. That’s not really an answer to your question. I have no insights on modern masculinity. I don’t think much about it. I see value in being emotionally available sometimes. I see value in getting angry sometimes. A sense of responsibility is a good thing to have. I don’t have a better answer than that.

Do the best directors you’ve worked with have common ways of going about their job?

They all know there’s no one right way to do anything. They’re constantly exploring or doing things wrong. The great thing about this work is that you you never truly figure anything out. It can always be better. It can always be more economical.

You’ve mentioned “economical” a couple times. Why is that quality important to you?

I’ve had the experience at the end of a play’s run of wishing I could go back and start with what I’d learned from doing it for four months — instead of having wasted energy on things that didn’t work. If I can start from an economical, efficient place then the performance is going to be better.

Is there a role that you can look back at and think, I did that as well as I could?

No. I try not to watch things that I do.

But you must have feelings about what worked and what didn’t.

There are ones that felt good, but I wouldn’t necessarily say that made them better. And it’s not my job to feel good about what I’m doing. It’s the audience’s job to get an effect from what I do. I can feel anything I want. But I do remember one of the first theater jobs that I ever had, right out of school, was a play we did at the Rattlestick Theater called Slipping. I didn’t know anything and that was good.

Because not knowing anything meant you didn’t have any expectations?

Yeah, exactly. I had no pressure. I was just doing what I’d gone to school for four years to do.

It’s a special feeling when you first get paid to do what you’ve always wanted to do.

Yeah. It was a miracle to be making a living as an actor. Nothing else mattered. What I get to do, it still feels like a fucking miracle.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.