Harlem-based artist Sable Elyse Smith has held onto a used children’s coloring book she found on 125th Street for about five years. The book, which features a smiling white woman character named “Judge Friendly,” was meant to teach children how to interface with court systems. Its faux-innocent treacle struck her as a form of propaganda, to familiarize children with the operations of the justice system, which otherwise would feel like they were working against their clear best interest — removing them from the care of family members who were sent to jail, for example. “I began looking through the book and was pretty immediately horrified by its language [and] images,” she told me. “Every time I went to a residency, the book traveled with me. I placed it prominently on every desk, and it kind of worked on [me] in the background, so to speak.”

This coloring book has now emerged as a kind of source text for her new show, BOLO: Be on (the) Lookout, currently on view at JTT, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, through December 16. BOLO is an acronym and code in American law enforcement that is often used to give information to alert officers of suspected “criminals.” Considering how Smith’s show, in conversation with her previous work on incarceration, takes up how archetypes of innocence are used as a cover for the targeting of vulnerable people, quotation marks around “criminal” are urgent here. The justice system designates certain people as threats and locks them up purportedly to protect the public it has designated as innocent and needing protection.

Smith says that “the show is dealing with power, visual seduction, the manipulation of language as apparatus of control and,” she adds, “a violence that might not be named as such.” This interrogation of banal or unregistered violence overlaps in its concerns with Smith’s 2017 solo exhibition Ordinary Violence at the Queens Museum (a version is now on view at the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee until late January). But while Ordinary Violence focused on her relationship with her father, who was incarcerated for 19 years, Smith is clear to point out that the focus of BOLO is not autobiographical. This show, however, fits into her larger interdisciplinary practice, which often uses text and tends to be about the fragmentary nature of freedom: where it might exist, where it is forbidden, and for whom.

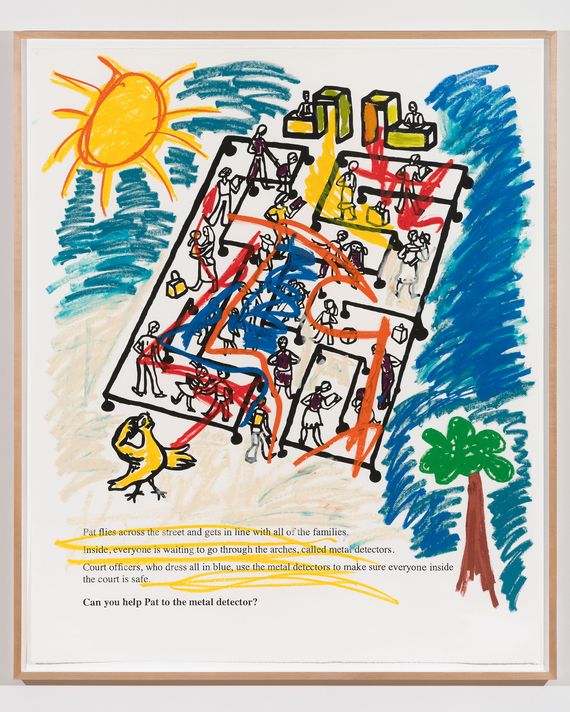

Smith’s new paintings blow up the coloring book, both literally and figuratively, scribbling outside the lines. Rich oils deface the picture book’s compulsory positivity. “Can you help Pat to the metal detector?” one painting reads. It’s speaking as if to a child, a fungible figure in American culture, whose formulated vulnerability becomes the justification for force, galvanizing violence in everything from policing and war to human-rights interventions. But not all children get to be this child, and it’s not only children who get to be this innocent.

“Innocence in this show is also played by a white woman,” Smith says, referring to the subject of a six-channel video piece called “Room One: The Watcher” (2018). The looping eight-second video depicts actor Julie Hagerty, on Conan O’Brien’s late-night show, reading from Richard Price’s 1992 novel, Clockers (which was adapted into a 1995 film by Spike Lee). “Did I ever tell you the first time I killed somebody,” she says, while laughing along with the audience. This line is heard throughout the gallery, becoming the show’s atmosphere. What’s the joke? Why, clearly, Hagerty would never pass as a murderer.

One of the most compelling pieces is almost hidden next to the video work. The collage “Maps for a Body Thirsty for Some Other Shit” (2018), made on vellum paper, features a snippet of a Doritos packet next to a diagnostic image. “It is also a quiet work among a collection of pieces that are yelling,” Smith says.

For the past year, Smith has been a 2018 artist in residence at the Studio Museum, alongside Allison Janae Hamilton and Tschabalala Self, and right now she’s deep into two projects. The first is a series of large-scale sculptures. The second is a feature-length script about queer intimacy, a collaboration with writer Akil Kumarasamy.

Focusing on the problem of innocence in BOLO fits with Smith’s more general interest in the undoing of language. Inasmuch as the coloring book can be filled in and disfigured, Smith offers us an inquiry into how things feel — the buzzing tension in her courtroom scenes, the smell of a yellow crayon. In the midst of the institutions that structure day-to-day life, Smith brings the relationship between politics and imagination so close that they touch. Even as the power of the state crushes, intimacy threatens to reign.