Monty Python celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. The legendary troupe (they’ve been called the Beatles of comedy because they’re so groundbreaking and British — except for Terry Gilliam) counts 1969 as its year of birth, because that’s when the first project bearing the Python brand reached audiences: the surreal and simultaneously silly and literate sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

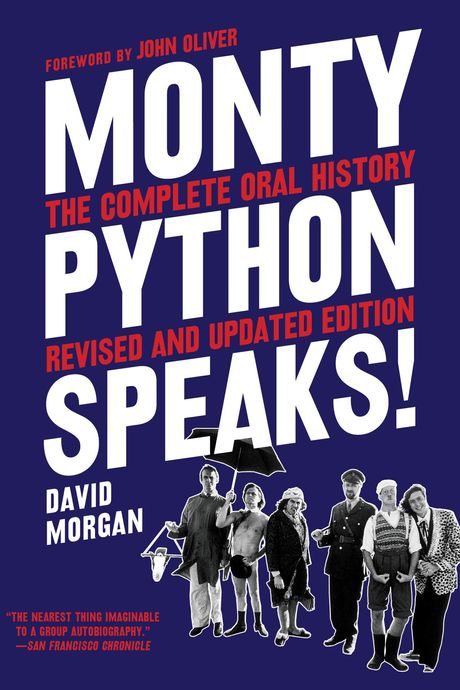

Lots of books have been written about Python — John Cleese, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Terry Jones, and Terry Gilliam — and the definitive, most comprehensive might be David Morgan’s Monty Python Speaks! First published in 1999 to tie in with the group’s 30th anniversary, Morgan expanded and updated it for the big 5-0. The Python story kept going after the late ‘90s, what with reunions, deaths, and Spamalot, the Monty Python and the Holy Grail–derived Broadway show. Here are nuggets about late-period Python found in the new material from Monty Python Speaks! The Complete Oral History, Revised and Updated Edition, which hits stores this week.

1. Their ideas for a reunion show sound sexist and terrible (but by design).

In March 1998, HBO assembled the surviving Pythons for an appearance at the U.S. Comedy Arts Festival. It was the first time they had all been in one place together in years, not since they lovingly roasted fallen cohort Graham Chapman at his 1989 funeral. At the Comedy Arts Festival, they even brought Chapman along, in the form of a pile of what were supposedly his ashes that they sucked up with a hand vacuum.

Everyone had so much fun that they talked about a real reunion show or tour, and HBO offered to sponsor something in Las Vegas. Terry Gilliam envisioned a tacky, old-fashioned Sin City revue, with the Pythons rehashing their old sketches while flanked with showgirls. Gilliam expanded on the concept with Michael Palin, inventing something called “the Pythonettes.” “You get six young beautiful girls who would do all the sketches,” Gilliam explained, and he and the rest of the guys would just sit on the side of the stage and offer commentary. “Yes, these are the girls, they’re doing great. ‘Well done, girls!’”

2. Eric Idle gave Mel Brooks the idea to do a Producers musical.

By the early ‘90s, Eric Idle thought Broadway musicals weren’t funny anymore. Gone were the broad, comic musicals in favor of Andrew Lloyd Webber melodramas. (Or, as he puts it, shows about “people with plates on their faces,” ostensibly referring to The Phantom of the Opera.) Idle wanted to make Broadway fun again, so he approached a master comic filmmaker, Mel Brooks, about adapting one of his movies for the stage. Idle wanted to make a musical out of The Producers, but Brooks turned it down because he didn’t think it was a good idea. However, he obviously changed his mind at some point, because he did his own stage version of The Producers, which won so many Tony Awards and made so much money that it made Broadway a very habitable place for silly musicals, and musicals based on movies. And that is what gave Eric Idle the idea for Spamalot, the stage adaption of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

3. Eric Idle made it difficult for the rest of Monty Python to refuse Spamalot.

Idle worked on Spamalot for two years without input from any of the other Pythons. He collaborated with a composer, hired some musicians, made demos of the songs, and sent a CD to Palin, Cleese, and the rest … which is how they found out about the project. While they liked the music, they still had reservations about how it would play out onstage. But Idle was so far along in the process by then that they really couldn’t deny him permission. “I suppose I was in that kind of protective, foggy, paranoid way where we felt, ‘What’s going to happen here? Who’s going to be in it?’” Palin recalled. “‘Are other people going to be saying our lines? Is this a good thing?’” So there were doubts, definitely doubts. Ultimately, it was strength of those initial songs that sold the rest of the troupe, more than the idea itself.

4. They reunited for the money (which they needed because of a lawsuit).

Mark Forstater, a producer on Monty Python and the Holy Grail back in the ‘70s, sued the troupe in 2012, arguing that he was owed a chunk of the substantial royalties and merchandising revenues generated by Spamalot. The Pythons countered with a claim that he’d actually been overpaid for years because of a Holy Grail–era accounting error. In what John Cleese calls “a very silly decision,” a U.K. High Court judge ultimately sided with Forstater, which cost the comedians £800,000, or roughly $1.2 million. And thus began Monty Python looking into the guaranteed cash windfall of playing a series of shows at London’s O2 Arena.

5. Some members have struggled with what it means to be a Python.

The Pythons have developed into seasoned legends and comedy elder statesmen, which has proved difficult for some of them to come to terms with. Gilliam wonders if he should let the work speak for itself and stay in the past, or if it’s okay to just keep flogging it forever. “It’s kind of our pension fund, and our children’s and children’s children’s futures, so you’re sort of torn between ‘Make more money for the kids’ and all that, or do we just keep Python what it always was and protect that little thing, that little gem, however flawed it might be?”

While he says that Terry Jones is the most “nostalgic” and celebratory of the old days, Gilliam thinks the group’s many solo projects are a function of trying to “escape” Monty Python. “I prefer my solo work, because it is mine,” Idle says. “I like my play, my books, my songs, the Rutles, so much stuff. Python was just a part of my life; it isn’t my fault people won’t let it go!”