Here, in brief, are the high and lows of Rob Delaney’s last five years: First, he moved his family halfway across the world to take a chance on a new job, a TV show he expected to be canceled in six months. It turned out to be pretty much universally beloved, and Delaney, who had spent a decade working under the radar, saw his career reach fantastic new heights. His face was on billboards and subway ads. His wife gave birth to their third child, a beautiful baby boy named Henry. Just when things could not be going any better, Henry, before his 1st birthday, fell ill. Delaney and his wife took him to doctor after doctor until a specialist discovered that the problem was about as bad as it could be: Henry had a malignant brain tumor. He had surgery to remove it and spent over a year in the hospital recovering. Then the tumor returned. In January 2018, Henry, only 2 years old, died at home surrounded by his parents and older brothers. Delaney’s fourth son was born a few months later. And through it all, he was still writing and starring in that hit comedy show. Called Catastrophe.

Now, a few weeks before Catastrophe is set to return to Amazon for its fourth and final season, Delaney is indulging the attendant press demands with a genial weariness. That’s how we find ourselves on an alarmingly balmy February morning, floating up the River Thames on a ferry as he points out the various sights of his adopted city. He is radiating exhaustion but manages to fire off a joke, or at least some deadpan nonsense, for each landmark we encounter: The Tower of London is both where the Crown Jewels are stored (true) and where he lives (false). One time, he almost visited the top of the Shard, the United Kingdom’s tallest building, but then he found out it costs £30 to ascend and decided to go eat a cheeseburger instead. When the Tate Modern appears on our right, it earns his solemn, if slightly overzealous, admiration. “I get intoxicated with the Brutalist architecture of London,” he says. “It’s indefensibly ugly stuff. I just want to caress it and live in it.”

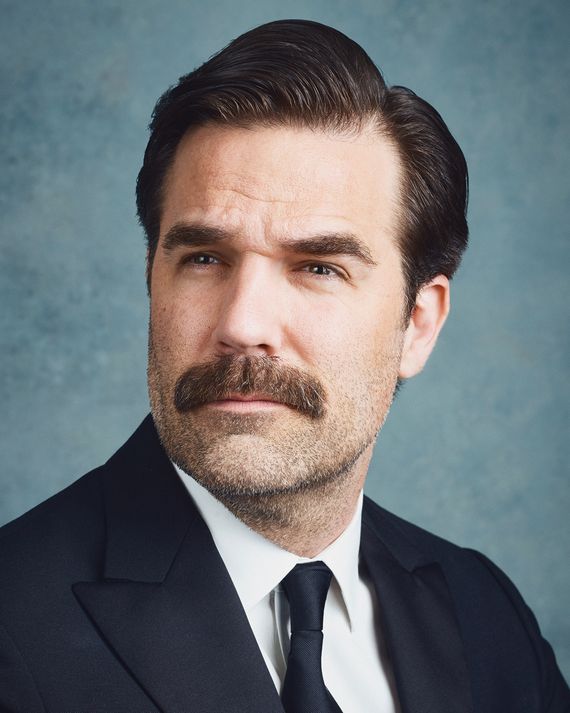

Even in his current, relatively subdued, state, it’s not difficult to imagine him lovingly and inappropriately fondling a large concrete building. Up until the night before our boat ride, he had a full beard, but his older sons, ages 6 and 7, helped him shave it off into a mustache so distractingly substantial it makes Tom Selleck look like John Waters. Paired with his black leather jacket and disarmingly friendly smile, it gives him the aura of a G-rated ’80s leather daddy or an off-duty state trooper. At 42, Delaney is sturdy and hirsute — six-foot-four and classically handsome, with a chin that belongs on paper-towel packaging — and he plays with his physicality in a way that’s reminiscent of an early-aughts Will Ferrell, though he captures a wider array of modern male ineptitude. (In one infamous photo, he’s stuffed into a minuscule teal-green Speedo, gazing stoically into the distance.) “Once I realized I’m kind of big and I kind of look like a straight,” he explains, “I thought I should just be a big idiot with it.”

Delaney is frequently a big idiot on Catastrophe. He also crackles with absurdist wit and envelopes you with heartfelt honesty and, more often than not, smothers you with visceral authenticity. His face is a circus of emotion. Before Delaney got the deal to make the show with the Irish comedian Sharon Horgan in 2014, he was known mostly for his popular Twitter feed, where he posted a steady stream of jokes so demented and filthy as to be unprintable here, and also most everywhere else. In Catastrophe, he plays an American businessman named Rob who goes to London for a work trip and embarks on a frantic one-week stand with Sharon, played by Horgan. When she gets pregnant, they decide to get married and make a go of it. The show is a gloriously vulgar, surprisingly poignant meditation on a husband and wife balancing a waning honey-moon phase with the realities of child-rearing and caring for aging parents. “A lot of people say, ‘Catastrophe, oh my God, that’s so vicious, no punches pulled,’ ” Delaney says. “But honestly, we tried to make an accurate show … the facts might not all be the same as someone’s real life, but the feelings, we wanted them to be.”

Delaney started writing Catastrophe’s final season just weeks after Henry died. He was in therapy and going to a bereaved-parents’ group and absolutely out of his mind with grief, but he wanted his kids to see him go to work. It wasn’t a distraction, but at least it added some kind of structure to his days, even if work often consisted of crying in the writers’ room in front of Horgan and their assistant. “By this time, I know them well enough where, if I just want to sit and cry for a while, I wouldn’t even have to get up and leave,” he says. “I had no qualms doing that, whereas I might have in, like, a 13-person writers’ room on a CBS sitcom.” This season is noticeably heavier (or, as Delaney sees it, more “nourishing”), touching on themes like spirituality, self-improvement, and, yes, grief.

Along with having to muster up an entire season’s worth of jokes so soon after losing a child, there was another baby on the way. Delaney found himself terrified that he would be too scared to bond with his newborn this time around. “I knew that I would ‘love’ him,” he says. “But I didn’t know if I would like him or bond with him, ’cause I didn’t know if I would be too afraid to.” That feeling dissipated a few weeks into his son’s life, but he sums up the whole experience as “totally insane,” adding that it must’ve been immeasurably harder for his wife. “How do you go to your own child’s funeral when you’re pregnant?” he asks. “I would like to carve a large bronze* monument in the center of town for her not going on a killing spree or picking up police cars and throwing them through windows.”

Though marriage and fatherhood inform his writing and stand-up, Delaney is highly private about his actual wife and children. On his Twitter feed, the references have usually been entirely fictional — recurring bits about his wife cheating on him with his karate instructor or raising terrible large sons with preposterous names like “Chesney and Tavin” or “Bryntallion and Grove.”

But in February of last year, the month after his son died, Delaney decided it was time to share what happened to Henry. “There was no way for me to not go insane,” he says, “and I wanted to be in charge of how that information got out there.” He started posting memories and photos of his son on Twitter, and he is determined to use his platform to destigmatize grief.

(“Tweets like this aren’t therapeutic to me, nor are they ‘updates.’ I just want other bereaved parents & siblings to feel seen/heard/respected/loved,” he explained in one.) In doing so, the comedian has become an envoy of sorts for the bereaved. “If it’s raining out, the people who don’t want to acknowledge that or understand it are offering you sunscreen. If you could just hand me an umbrella or even be like, ‘Wow, it’s pissing out,’ then I’d feel sane,” he says. “Grieving people aren’t lepers. They don’t need to be handled with kid gloves. They know what happened. Just acknowledge it, you know?”

When he talks about Henry, Delaney picks at his fingernails and speaks gently and deliberately. “If you observe me through a telephoto lens or something, you might not know that I’m grieving all the time,” he tells me.

“I’ll have a memory and start to cry sometimes. Or I’ll look at my watch and notice it’s coming around the time when I would have changed his tracheotomy dressing for the day, and I’ll be sad I’m not doing that.

“He’s absolutely still my son, and he commands a big percentage of my attention each day. So I just try to not resist that or hate it or fear it,” he continues softly. “He’s my son. I loved him when he was alive. I still love him and talk to him and think about him every day.”

When Delaney was 25, he got blackout drunk and drove his car into a Los Angeles Department of Water and Power building. His drinking had been a problem since before his high-school days growing up in the seaside suburb of Marblehead, Massachusetts. It followed him to New York City, where he studied musical theater by day and drank so much that he regularly wet the bed by night. Six months after he moved to L.A. to pursue a comedy career, it finally caught up with him. The accident all but destroyed him physically — he broke his right arm and left wrist and tore both knees open to the bone. He was thrown in jail, then did a stint in rehab and a halfway house. Last month, he celebrated 17 years of sobriety.

A muted version of Delaney’s accident appears in Catastrophe’s third season, when Rob, a secretly lapsed alcoholic, crashes his car while picking up Sharon. In his 2013 memoir, Delaney devotes plenty of space to gut-wrenching stories from rehab and the halfway house — and highly specific memories of how hard it was to masturbate with two broken arms. He’s excellent at dredging up humor from the muck of life, as well as its more minor humiliations, like the times in his youth when he was rejected by modeling agencies. (The Catastrophe scene in which Rob, recently fired from his job, unsuccessfully tries to get cast as a big-and-tall model had me weeping with laughter.)

Henry’s death is far too recent and devastating to inspire any specific creative output, and maybe it always will be, but it has nonetheless changed the way Delaney operates. “It burned away a lot of stuff that I don’t really care about,” he says. “I’m not going to talk about stuff that doesn’t genuinely inspire me or anger me or make me afraid. One big thing is that I still enjoy writing. I still enjoy being funny.”

And he is still deliriously funny. During a recent Sunday-night show at an intimate club near his house in Islington, he stood on a small stage and told the crowd about the time he spilled boiling mint tea on his crotch. He comes to this club every two weeks or so to test out new material, much of which concerns being married and having young children. The mint-tea story, for instance, ends with him stripping off his pants and dunking his genitals into a nearby cup of water, only for his wife to enter the room and witness this “aquarium of nightmares.” Another story is about the family’s pet lizard, Jackie, escaping for a month. Delaney’s sons, who had begged for the lizard only to immediately abandon all caring and feeding duties to their father, asked him if Jackie had died. “Yeah, it’s fuckin’ dead,” he says. “It’s dead, you killed it, and it’s dead and it’s in hell.”

Delaney’s Twitter presence, once a flood of dirty jokes, is now merely a trickle of dirty jokes. They are vastly out-numbered by the political posts he shares constantly with his 1.5 million followers. After his car accident, he became an almost single-issue voter on health care. The extraordinary treatment Henry received from the U.K.’s National Health Service turned him into a fanatical Medicare for All advocate, and after the 2016 election, he joined the Democratic Socialists of America. (He downplays his involvement, calling himself the “least-useful type of person in the organization,” though he filmed a video promoting Medicare for All that racked up over a million views.) “I was so excited when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez surpassed me in followers,” he admits. “All I want to use the internet for is to make more teenagers into card-carrying socialists in the U.S. and U.K.”

He’s not planning on leaving money behind for his children beyond what’s required for college or in case of disability — a decision he made years ago when drawing up a will, because he abhors inherited wealth. And that was before he became flush with acting opportunities: He had a part in Deadpool 2 last year and is in six other upcoming movies, including Jay Roach’s untitled Roger Ailes project, in which he plays a fictional producer on Megyn Kelly’s show opposite Charlize Theron. If anything, Delaney says his rising star has made him even more committed to his ideals. “Not long ago, it was me taking the bus to go do stand-up while my wife was the breadwinner teaching at a public school,” he reflects. “It happened so quickly for us as to be silly. Now I know it’s just a joke and a game. The more successful I’ve gotten, the more I’ve been like, Oh God, this is so rotten what’s happening.”

Delaney and I hop off the river bus at Parliament Square and are back on dry land for barely two minutes before we find ourselves caught up in a youth climate-change protest. As we squeeze through the crowd of schoolchildren, two adults separately stop Delaney to take selfies and tell him how much they love his show. This prompts three preteen boys to pause their gleeful chant of “Fuck Theresa May!” — which was objectively adorable to witness — and whisper among themselves, wondering who the celebrity is in their midst. “Excuse me,” one finally musters the courage to ask. “Are you Lemony Snicket?”

Delaney erupts into laughter before regretfully informing them that he is not the wildly popular children’s-book author. Other actors might be wistful to see their hit show ending just as they’re becoming famous for it, but Delaney is ready. He has said all he wants to say about the early years of a marriage and parenthood. What he wants now is some time to sit and think about what to say next.

He is also more aware of his mortality than ever before, and he’s embracing it. “Even the people I love most are gonna die, and they could die before me. Which is just bullshit,” he says. “Since I know that could happen today — I could slip and bang my head, and that would be it — I want to make stuff that is a small, positive contribution.”

For the immediate future, he has other plans. Delaney bought his wife scuba-diving lessons for Christmas — she’d recently given birth, and he wanted to get her a gift that suggests adventure and exploration. But scuba diving, it turns out, is a buddy sport; having a partner tends to minimize the risk of dying alone underwater. Delaney just finished a training program, so I ask if the couple has any upcoming trips.

“We’re going to a fucking pond near Heathrow. Talk about the bleakest surrounding,” he says with a touch of grim amusement. “Honestly, I’m excited because when would you ever do that? Anybody can scuba dive in the Bahamas. It takes a special kind of person to kit up and hop in a pond by the airport.”

*A version of this article appears in the March 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

*This article has been corrected to show that Delaney said bronze, not brown.