Penny Lane and I are standing in the middle of Abracadabra, a Halloween store in New York’s Flatiron District, watching a life-size animatronic zombie puke into a trash can. Moments earlier, we’d both thought it was a real person and almost greeted it formally. Watching the zombie tilt its head back, then lunge forward and expel green-orange vomit, Lane, a filmmaker who’s just made a documentary about the rise of the Satanic Temple, titled Hail Satan?, lights up. She turns to me, grinning: “This is really phenomenal, isn’t it?”

Before we go any further, let’s get this out of the way: Yes, her real name is Penny Lane. Yes, it is on her driver’s license. She addresses this immediately and directly on her website’s FAQ section, which is devoted exclusively to the questions she gets daily:

Is “Penny Lane” some sort of stage name or nom de plume?

No.

Are you saying that “Penny Lane” is your real name?

Yes.

Did you have your name legally changed to Penny Lane?

No. Penny Lane is my given name. It’s on my birth certificate.

Did your parents like the Beatles?

Clearly.

Having been named after a Liverpool street is hardly the most interesting thing about Lane. Though it’s hard to pinpoint what is, exactly. There’s a lot to choose from; dozens of films that, as Lane puts it, are “stories about stories” — stories about the way people tell stories and the narratives they construct around themselves. Maybe it’s that she once made an animated documentary called Nuts! about a man who transplanted goat testicles into human men to cure impotence. Or maybe it’s her thoughtful animated short about the white supremacist who invented Sea-Monkeys. (At one point in the film, Lane intones, “This is where things get a little bit strange — and a lot darker,” which could stand as a description for all of her work, if you tacked on “and funnier” at the end.) It could be her early, avant-garde work like 2010’s The Voyagers, which boldly compares her incipient marriage to the launch of two unmanned 1970s spacecrafts, or 2005’s Sometimes I Get Lossy, a one-minute series of pixelated close-ups of Lane’s face that she describes as “what happens when you spend all your fucking time in front of a computer.” Possibly, it’s We Are the Littletons, a spooky, lightly campy vignette of a family who put Lane up in their farmhouse for a winter, then sent her letters warning her not to let their estranged daughter inside.

Or it might just be Hail Satan? The documentary marks a breakout for Lane: the first film she made that was picked up and given a wide theatrical release by a major distributor (Magnolia Pictures); the first to inspire a series of Penny Lane retrospectives, including one held last month at the Museum of the Moving Image; and the first to feature a person impaling a pig’s decapitated head on a stake. The movie has already changed her life — she recently quit her teaching gig and, for the first time in her nearly 20-year career, plans to focus solely on filmmaking. And, of course, it forced her to ask herself the question many viewers (myself included) will likely ask themselves while watching Hail Satan?: Wait, am I a Satanist?

Lane and I met at the Halloween store because the Satanic Temple was essentially born inside one. Hail Satan? tracks the rapid, bizarre, amusing, and genuinely heartwarming ascent of the Temple, which began as something of a political prank, only to turn into a religious refuge for rebels the world over. In 2013, three men named Lucien Greaves (a “double pseudonym,” he wryly explains in the film), Malcolm Jarry, and Nicholas Crowe traveled to Florida to host a rally “supporting” Governor Rick Scott’s bill legalizing student-led prayer in public schools. If Christian kids could pray in schools, the three men asserted, so could kids of any faith — including Satanists. At this point, Greaves was the only true Satanist in the bunch — a noncommittal, unaffiliated Satanist who didn’t believe in the existence of a literal devil (most don’t), but did believe in the adversarial, individualistic nature that Lucifer represented. As Lane puts it, Crowe and Jarry just “wanted to do this hilarious prank, and they got Lucien involved because they needed an actual Satanist to get their set-dressing right.” That set-dressing included a demon costume purchased from — where else? — a Party City.

The trio recorded footage that would eventually become part of Hail Satan?, originally thinking they’d produce a mockumentary about their trip to Florida. But pretty quickly, things got serious. “At first, Lucien was just happy to consult on this brilliant political prank,” says Lane. “But then he realized, ‘Wait, this could actually be pretty cool. But we can’t have a fake Satanist at the center.’ So he kind of reluctantly steps into the role of Lucien Greaves and becomes the spokesperson of what will soon become the Satanic Temple.”

Lane and I stop in front of a rack of oddly sexualized children’s costumes. She pauses mid-sentence. It’s the first and only time she appears disturbed by something during our conversation. “This is very freaky,” she says. We both stare silently at a photo of a young boy dressed as what can only be described as a cop from a ’70s porn flick. We quickly move on to the wig section.

After the rally, the Satanic Temple movement grew rapidly, hosting various protests across the country, all with an undergirding principle: Christianity has no place in state or federal government. During one protest, captured cheekily in the film, the Temple rebuked Westboro Church founder Fred Phelps’s virulent homophobia and bigotism by inviting queer couples to make out atop his mother’s grave, proclaiming that she had become a “lesbian in the afterlife.” “They wanted to point out the hypocrisy of Christian lawmakers, who say things like, ‘Religious freedom’s really important, and that’s why we need to have prayer in schools,’ but then also say, ‘Oh, but only the religions that we personally think are good,’” says Lane, pausing in a biblical-themed corner to stroke a gray Jesus beard.

Lane began filming her own documentary after reading a Village Voice article by Anna Merlan about the Temple, joining them with her camera about a year and a half into the mockumentary-turned-serious-doc. “[Merlan] was the first one to really write a real story about them, that wasn’t just, like, assuming it was a joke. And her article was very foundational in my understanding of what was going on,” says Lane. “She’d actually done reporting, as opposed to everyone else, who was like, ‘Who are these assholes?’”

Things came to a serious head for the Satanists — both legally and in terms of the Temple’s visibility — when the Temple pushed to erect a statue of the demon Baphomet on the lawn of the Oklahoma State Capitol, which had recently become home to a monument of the Ten Commandments. Lane captures the resulting drama with a sense of glee and irony: At one point, a man unaffiliated with the Temple rams his car into the Ten Commandments monument, toppling it; at the unveiling of the second Ten Commandments monument, Greaves, sporting sunglasses and a sardonic grin, hops into the local state representative’s celebratory live Facebook feed to remind viewers about the clause in the Constitution that insists on the separation of church and state.

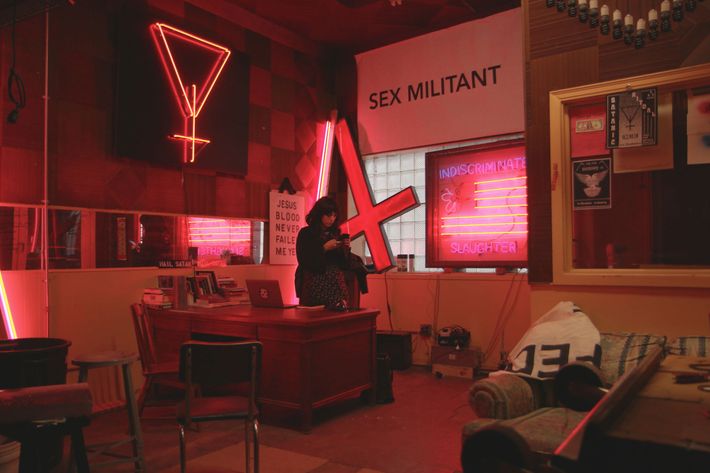

The Baphomet initiative received the most media attention of all of the Temple’s work. In the years since, the Temple’s membership has grown by the hundreds of thousands, with chapters across the world and a set of its own Seven Tenets, including, “One should strive to act with compassion and empathy toward all creatures in accordance with reason,” and, “One’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will alone.” Its members have adopted the gothic theater embedded in the Temple’s DNA, taking on their own pseudonyms — Jex Blackmore, Lanzifer Longinus — and hosting Black Masses, during which they pour wine over each other’s naked bodies and mount pig’s heads on stakes. It’s all done with a bit of a wink — pageantry for the sake of it.

“It’s an incredible origin story,” says Lane, who is now seriously considering purchasing a pair of $15 Pentagram pasties. “But people like to point at that story and say, ‘Well, how can you take them seriously? Look at how it began.’ This idea that you can’t take them seriously because of the connection to this store that we’re in right now — this totally misunderstands how a religion would get born,” she says. “Think about all the other religions’ origins. There’s pretty good reason to believe that Jesus was a good sleight-of-hand artist who may have been convincing people that he was performing miracles. Or you’ve got someone like Joseph Smith, pretending to find golden plates in the woods. What I think people are missing is that religious identity is something you perform. It isn’t natural: You go to the building, you dress in a certain way, you stand when you’re told, you read the words, you take the cracker. It’s all this kind of ritualized performance.”

Lane gives the Temple credit for its creativity and bravery. The Satanists know it’s easy for you to dismiss them, to laugh at them — so they laugh first. “They haven’t been around for thousands of years, so they’re kind of trying to come up with what this looks like. What would a ‘Satanic ritual’ look like? What is a Black Mass? What is a destruction ritual? It’s all new, and they have no money. Occasionally, I’d be like, ‘Do you think you should get better cloaks?’” But she also clarifies that the Temple isn’t the be-all and end-all of Satanism in 2019 — in fact, many Satanists prefer to be on their own, free from any tenets or constraints, which is something the Temple grapples with in the film.

Wasted wine aside, many of Satanism’s essential ideas — freedom, agency, compassion, social justice — are impossible to disagree with. I ask Lane if she was swayed enough by the group’s logical humanity to call herself one. “I thought about whether I was, but I didn’t come to that decision. It was sort of like, ‘If you have to think about it, you’re not,’” she says. “I’m onboard with all of it. I’m very Satanically aligned. But I’m not a Satanist.” In fact, Lane grew up without any religious affiliation at all, but she says the Temple convinced her that religion itself was not “fucking mental.” “It was a huge revelation for me, how it functions in people’s lives,” she says. “I now understand religion not as a list of beliefs, but as almost like a machine for producing meaning and organizing your life.”

Making the documentary not only helped Lane see herself in throngs of religious believers, but it helped sharpen a sense of her own identity as a filmmaker. She tells me that, as a young director, much of the filmmaking process “embarrassed” her. “I found it very difficult to direct a crew, to be in a situation with a camera person and a sound person. I kept making mistakes, so I just stopped doing it. So I went into archival filmmaking and animation and all kinds of things, where the mistakes were very private,” she says. “Anything I did that was stupid, you didn’t see.” Making Hail Satan? represented all of her worst fears: It was her first film with a crew, the first film where she had to follow her subjects for years, her first, as she puts it, “normal documentary.”

She credits her producer, Gabriel Sedgwick, with “taking on all the parts of filmmaking I’d felt insecure about” and helping her make the most “ambitious film of my career.” Now that she’s done, Lane says, she feels her options are “limitless.” “Even a year, two years ago, the fear of not knowing how to do something would have been a pretty salient decision point for me,” she says. “I can’t really complain, but I do sometimes feel very frustrated with my younger self, where I’m like, ‘What were you so afraid of?’ Now I just feel like anything is possible.”

We stop again in front of a series of costumes branded “cozy,” which is to say, costumes that cover body parts. Lane gasps with joy, clasping her hands together. “I have now found the Halloween costume that I believe in,” she says. “I am a cozy bat.”