On last week’s The Good Fight, when Maia aggressively procured a private office from another third-year associate, it was a meme-worthy moment, completing her Roland Blum-triggered transformation into a ruthless, unapologetic, take-no-prisoners badass. Gone was the Maia from the first season, whose confidence was minimized by her father’s misdeeds and her own junior status at the firm; now she’s more like the velociraptor in Jurassic Park who learns to open a door — she’s discovered her own power, and it’s intoxicating to witness, as empowerment stories generally are. If she had to slash and burn to get there, so be it.

Yet the show, to its immense credit, has not let this incident go without further examination. Maia got her office by appealing to the partners, who then kicked its black occupant back out into the open rows of desks along with the other low-ranking associates. This is not the reason why she gets fired at the end of “The One with Lucca Becoming a Meme,” but it does inform an episode that uncorks a lively discussion over the racial disparities that have been simmering at the firm for a long time. Despite Reddick, Boseman & Lockhart being understood as a minority-run operation with mostly black partners, the reality is that white employees are paid better and treated more charitably, and Maia is Exhibit A.

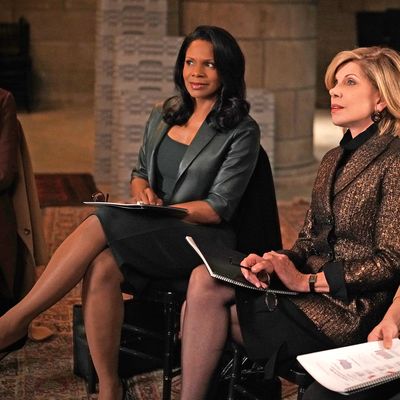

At issue in the episode is Maia’s arrest over the hospice drugs that Roland had left in her car. Calling the police was Roland’s revenge for Maia getting a favorable plea deal for her client over his, but there are questions about her judgment in allowing that to happen, even understanding Roland’s propensity for mischief. The disciplinary board opens the episode with some division over whether Maia should be fired or suspended: A couple of the board’s black members remind them that an associate was terminated over drug charges not long ago, and that the firm should be consistent in its “no tolerance” policy. Diane argues that circumstances are different here, because Maia was in possession of drugs, not using them, and the context for how she got them matters. At the end of the meeting, Adrian agrees to reconvene four days later for a final decision, but the vibe in the room is that Maia will get off with one-week suspension.

Then circumstances change, through a deftly orchestrated series of events that causes the higher-ups at the firm to reframe the discussion. It starts with an incident in the park, where an officious white woman starts harassing Lucca over her baby and phones the police with her suspicion that Lucca isn’t the child’s real mother. Someone captures the scene on cellphone video, and in true Good Fight fashion, a ripped-from-the-headlines phenomenon — in this case, white people calling the cops on black people, and having it backfire virally — becomes grist for the mill. At a meeting to discuss how to deal with the threats Lucca has been receiving, past instances of police violence against unarmed black citizens come up, and she notices a curious phenomenon: The black people in the room all know the names of the victims — Philando Castile, Botham Jean, Laquan McDonald — but the white people can only vaguely recall the circumstances of the shootings.

(A brief scene afterwards is particularly striking. Marissa confronts Lucca with a defensive attitude that feels absolutely true to white progressives who are slow to recognize their own racial blind spots. “So you think I’m racist?” she asks. “No,” replies Lucca, “It was just an observation.” Marissa then snaps back that her parents went to Selma, and leaves in a huff. This back-and-forth isn’t hugely consequential in the episode’s plotting or in Marissa and Lucca’s relationship, but it’s just a keen example of how difficult it can be to talk about race, even among friends, without it going off the rails. By contrast, Diane slipping off to look up and memorize the names seems the wiser choice.)

The decision to have Jay escort Lucca to and from work leads to the firm’s racial scab being picked clean off. The two get to talking: Lucca has been noticing an influx of majority-white hires and it bugs her. Jay observes that the best offices and the best pay have been going to white employees. When Lucca asks for a salary breakdown, Jay warns her, “When you fire that bullet, it will start a war.” But what Jay doesn’t realize is that Marissa, an investigator far less experienced than him, is now making the same amount of money. There’s a specific reason for that — she has been advising Julius’s bid for a federal judgeship on the sly, and he’s rewarded her for it — but his outrage triggers the release of a salary breakdown to everyone at the firm.

And in the best spirit of The Good Fight, the whole place goes productively haywire. Racial divisions within the firm grow more entrenched, hostilities are brought out into the open, and the partners are forced to answer for running the business in a way that’s plainly inequitable. The simple explanation, from Adrian, is that white employees are paid more because the threat of them leaving for another firm is greater, and that he’s learned to “accept a certain amount of bias” in exchange for protecting its long-term viability. “I have to worry about the racists I can see,” he tells Liz. “When I solve that, I can turn to the racists I can’t see.”

But this all circles back to Maia, who gets fired. Would she still have a job if Lucca hadn’t been harassed in the park, become a meme, gotten death threats, been escorted home by Jay, and pulled the thread on racial disparities within the firm? Almost certainly yes. Is it unfair that Maia loses her job under these circumstances? The show suggests not. This is not the first time she’d benefited from the firm’s racial largesse, and Liz’s deciding vote in the 6-5 judgment feels like a fair step to redress the balance. We probably haven’t seen the last of Maia, who’s been a major character from the start, but The Good Fight has the boldness to make us see her in a different light. And maybe see ourselves in a different light, too.

Hearsay

• No “GIF of the week” candidates this week, but Maia’s “Fuck You” note appears to be showing some viral potential. Save it for your least favorite politicians and pundits.

• Marissa and Jay looking in on Maia meeting with the disciplinary board: “It doesn’t look good,” says Marissa. “She’ll be fine,” replies Jay. His delivery in that exchange sets the tone for the whole episode.

• The show references two singers at once in the subplot about Diane’s group forcing a popular singer to take a political stand and denounce the alt-right. This happened most famously with Taylor Swift, who’d refused to talk about politics until she was embraced in some white supremacist circles. Her decision to come out in favor of two Democratic candidates in her home state of Tennessee — Phil Bredesen for Senate and Jim Cooper for the House, both of whom ultimately lost — led to a predictable backlash, but also a surge in registrations from young voters. The nasty message about the singer’s trans sister references Jackie Evancho, a 17-year-old America’s Got Talent alum who’d agreed to sing at President Trump’s inauguration. She was disappointed to learn later about his proposed transgender ban in the military.

• The Jonathan Coulton explainer-ditties have been such a great addition to the show, including this week’s bit on how memes can darken and obfuscate. There was once a time when Pepe the Frog was an innocent character in Matt Furie’s Boy’s Club comic. Now it’s widely known as a favorite alt-right meme. Or, to put it in Coulton’s words, “And then, tada, a cartoon Nazi frog.”