One afternoon in May, inside his modern Beverly Hills home, Lee Daniels digs his toes into a sitting room’s biscuit-colored flokati, visibly restless as he toggles between two iPhones while waiting for Fox to announce the fate of Star, his Empire spinoff. He’s in jeans and a black hoodie embossed with the word blackman in black letters. “ ‘Nothing so far,’ ” Daniels says, reading from his phone. “ ‘No love yet for Star.’ ” By day’s end, Star would be canceled. The following week, Fox announced that the upcoming sixth season of Empire would be its last and that, in light of his assault scandal, Jussie Smollett would not be returning as Jamal Lyon, the embattled gay son of the Berry Gordy – like Lucious Lyon. That the network declared his shows dead and dying could easily be seen as a career-torpedoing setback, but Daniels, a self-described “hustler,” views cancellation as just an invitation to test his ingenuity and nerve. “I’m NOT letting them STOP the CULTURE. SORRY!” he wrote on Instagram a week later (handle: @theoriginalbigdaddy), when announcing his ultimately fruitless effort to locate a new home for Star.

Daniels is a certain breed of Hollywood magician, serially pulling career rabbits out of his hat beginning in 1983, when, flush with cash from a nursing business he’d sold, the Philly native, decked out in Armani, drove his Porsche to the Purple Rain set on the Warner Bros. lot and officially entered show business as the world’s fanciest production assistant. Decades of bootstrapping as a talent manager, movie producer, and indie-film director followed, until his 2009 breakout, Precious, made him the first African-American to be nominated for both the Best Director and Best Picture Oscars. Precisely what his post-Empire career will look like isn’t certain, but the perennially restless Daniels is nurturing a number of seedlings. There’s his political-correctness comedy for Amazon and a growing list of not-quite-green-lit projects, including a Terms of Endearment remake with Oprah in the Shirley MacLaine role, a gay-superhero comedy called Superbitch, and a Billie Holiday bio starring Andra Day.

Andrew Goldman: You have never been pigeonholed, but I read about this Whitney Cummings–and–Lisa Kudrow comedy about #MeToo and it didn’t seem to me like it had Lee Daniels written all over it.

Lee Daniels: It is, because it rattles the cage. It’s not a #MeToo comedy. It’s a look at the world and the crazy that we’re living in right now. It’s what this whole movement means to three different generations of women and just where we are in society with being woke.

Is it an issue you have strong feelings about?

I’ve been itching. You know what happened to me? Around the time of the whole Harvey Weinstein thing, I was brought into Fox HR. They were saying, “This is all preventative,” but I literally saw my career gone in front of me as these two white women and one Asian-American woman basically were saying you can’t use certain words. Like, you couldn’t use the B-word.

B for bitch?

Mm-hmm. I said, “Okay.” And I think they said, “You can’t look people in the eyes too long. Be careful with touching.” These are all things that I do in my room when I work. And then they said, “And you can’t say the N-word.” I was shook.

Shook because you thought what they were saying was silly?

I thought it was inappropriate to tell me that. I said, “Hold on. If I can’t say nigga to a room of niggas, you wouldn’t be here. Because Empire wouldn’t be created. You two white ladies and you Chinese, Asian lady, rather, you cannot tell me how it is that I can create.” Then it led to a bigger conversation of me being afraid to be me on the set and how I make my movies. I said, “I can’t have this conversation. I need to know who I can call on you. Because you have me triggered. You’re not going to play these games with me.”

What was their response?

What could they say? I mean, they turned red-faced. Listen. You’re not going to tell me what [the N-word] means to me. I have a play right now where the whole first five minutes is a preacher saying, “Nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga, nigga. Obama is my nigga. Obama is your nigga. Obama is the nigga.”

It’s interesting because one of the things you notice immediately in Empire is you don’t hear the N-word, at least in the first seasons. Why not?

I go through phases. I go in and out of owning it, and I think that we chose purposefully in the very beginning of that. It’s a really tricky word. But we did use faggot, which had never been done since Archie Bunker. So that was a big accomplishment, and I fought tooth and nail for that because it warranted it.

In the first episode, Lucious tells his son Jamal, who is a singer, that he needs to stay in the closet because the black community will never accept a “sissy.” Do you think homophobia is different in the black community?

I can’t speak for today’s generation, but that has been my experience. My son, who’s 23, came home with a guy once who was clearly gay. I knew my son was terminally heterosexual, but I go to my boyfriend, “He’s out there with a gay guy.” And so he says, “Do you have a problem with it? Go out and ask him.” So then I finally mustered up the courage to go out and say, “Is there something you want to share with me? You know he’s gay.” He’s like, “And?” I said, “Are you?” He goes, “What if I were? Is that bad? You’re gay, what are you getting at here?” I felt so stupid. I mean, he dates women, and he made me look a fool.

So at that moment, did you feel like you had actually inherited some of that homophobia you had been a victim of as a kid?

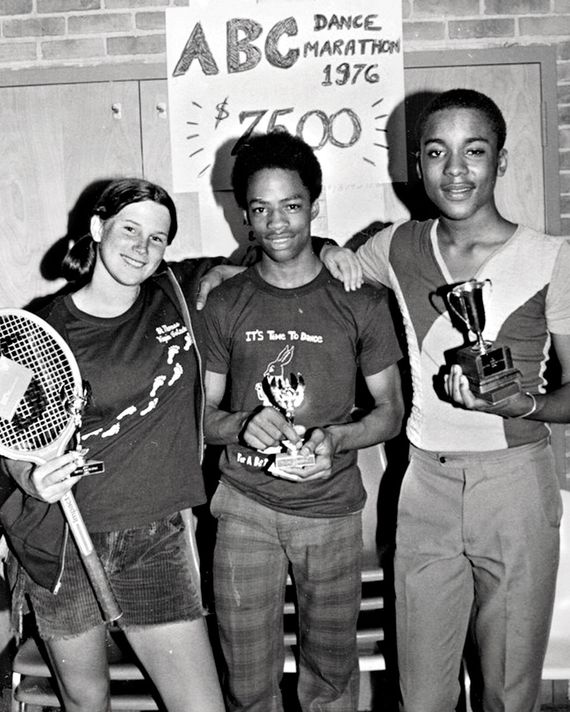

A little bit of that and a little bit of fear for him going through what I went through as a gay black man. Fear is what my mom felt for me, for sure. My mother didn’t want to admit it, but she knew I was gay. It was in the ’70s, and my daddy had just died. She instinctively knew that I was either going to get bullied, shot, or end up in jail. So she took me out of the ghetto and put me into this all-white environment, Radnor, which is on the Main Line in Philadelphia. It’s very fancy, wealthy, and it might as well be private. I was probably one of two or three blacks in my class. Radnor introduced me to theater; it introduced me to an awakening of what wasn’t there for me in public schools in Philadelphia. You’re looking at somebody that’s supposed to be in jail, a statistic. My brother didn’t stay out of jail.

You adopted your brother’s two infant children when he went to jail and their mother was unable to take care of them. You’ve said he’s homophobic to the point where your kids don’t see him.

I don’t think he’s that way anymore, though. I think that’s the beauty of Empire.

Empire changed him?

Oh, for sure. I think that he embraces his celebrity, because when Empire comes on in the prison, you’d better not fucking make a move. Thousands of men throughout every prison in America sit and watch silently. Because of Empire, he saw me as something other than somebody gay. I think that’s beautiful, and I love my brother very much now.

The reporting that’s emerged about the Jussie Smollett case suggests that he faked a racist, homophobic mugging in order to get paid more money on Empire. You initially publicly supported his story. Are you embarrassed?

I’m beyond embarrassed. I think that when it happened, I had a flash of me running from bullies. I had a flash of my whole life, of my childhood, my youth, getting beaten.

Knowing Jussie, would you have suspected this from him, or did this come out of the blue?

Blue. Blue.

It’s got to feel like a huge betrayal.

If it turned out that he did it, was guilty, and all of it’s accurate.

Wait, there’s really doubt in your mind that he didn’t make the whole thing up?

Of course, there’s some doubt. I’m telling you that because I love him so much. That’s the torture that I’m in right now, because it’s literally if it were to happen to your son and your child, how would you feel? You would feel, Please, God, please let there be that glimmer of hope that there is some truth in this story. That’s why it’s been so painful. It was a flood of pain.

Did you read the Chicago Tribune’s coverage of it?

I didn’t read any of it. I was too busy putting out fires.

Because to me, the Tribune’s reporting didn’t leave much in the way of doubt about its being anything other than a hoax. What would the scenario look like of him telling the truth?

We weren’t there. I can’t judge him. That’s only for the fucking lady or man with that black robe and God. I had to detach myself and stop calling him, because it was taking away the time I have for my kids, the time I have for my partner. It was affecting my spirit and other shows, everything.

You are a showman and a provocateur. A friend of mine remarked that she’d never heard of Smollett and all of a sudden he was the most famous guy in America.

What do you make of that? Think about it. If he didn’t do it, he’d be Martin Luther King right now. He’d be some sort of god.

You mean if he’d gotten away with it? I wondered if any part of you, as a showman, thought, Hats off to this guy for making himself a household name.

Yeah. Kudos. Yeah.

In the first episode of Empire, we learn that Lucious Lyon has ALS, a terminal disease. Eventually, we find out it was a bad diagnosis. But wasn’t it a bad idea to announce that your leading man has to die? I mean, you could have just given him melanoma or something.

I didn’t know the show was going to be picked up. Directly after the pilot, I was supposed to go off to do Richard Pryor with Mike Epps. I just assumed somebody would take over the show.

So you didn’t worry about what was going to happen to him?

No. I didn’t think about that, and they said, “Your show is picked up,” and I said, “Huh?”

Who called you and said, “You can’t kill Lucious”?

We called us and said we can’t kill Lucious. There was no show without Lucious. Are you kidding me?

Making Terrence Howard a lead in a network show seems like a risky call. He’s somebody who has been described for 20 years as difficult.

He’s one of my best friends. And I can count on my hands how many friends I have.

He’s quite eccentric. He developed his own mathematics in which he believes one times one equals two.

Sometimes I don’t know whether it’s a show. I do believe that he believes it, so maybe it’s not a show. So I protect him, because he’s like my brother and I trust him. I trust him with my life.

He’s a great actor, but he was also accused of hitting women on at least six separate occasions. Should Terrence have kept his show, considering what he’d been accused of?

I have no comment. I have nothing really to say about that.

Jeffrey Tambor and Kevin Spacey lost their shows after they were accused of improprieties. Should they have lost their shows, then?

I don’t know of the Jeffrey Tambor thing. I do know of Kevin Spacey firsthand, and I’m happy that he got his comeuppance.

It was a little surprising to learn that Fox was ending Empire. Do you think the Jussie situation played a part in that decision?

Certainly, that played a major part. But come on, man. I think that it’s been a good run. Empire in its current iteration may be over, but Empire is far from over.

I don’t understand. Are you taking the show to another network or streamer?

I don’t want to contradict the studio, so I have to say that it’s over.

That is so confusing.

I’m sorry. Well, we’re trying something out, and if it works, then Empire is over and we have a great spinoff. And if it doesn’t, then Empire may not very well be over. But the intent is to have our last season with a great spinoff. I don’t know if that makes any sense at all. We’re in the writers’ room right now, discussing [Empire’s final] fantastic, bombastic season, which is going to shake you by your roots.

So are you plotting the death of a bunch of characters?

My darling, do you think I would be stupid enough to share that with you?

The Root wrote that it was a “troubling trend” that Fox not only announced it was ending Empire but also canceled all its shows with black leads: Lethal Weapon, Rel, Proven Innocent, Star, and The Cool Kids.

Yes. It’s not just my show. Clearly, there’s obvious stuff going on.

Like a whitewashing of the network schedule?

I think it’s very obvious. I was disturbed by it. But I don’t think Empire had anything to do with the whitewashing. Empire sort of lives in its own space at Fox, but I do question the agenda. Any fool could sure see where that’s going.

The most devastating thing on Empire might have been the scene in the pilot when Lucious, in flashback, discovers his very young son wearing his mother’s heels and takes him outside and throws him in the garbage can. Did something like that actually happen to you?

Oh yeah, it happened. They’re just sort of scattered memories, but I was 5-ish, I came down the steps with my mother’s high heels on, and that’s what happened. I don’t remember much of anything except the dark and smelling the eggs and then thinking that I was Aladdin on a rug. It took me a long time to forgive my father and to understand that this is something that he could not comprehend at all and he thought he was going to beat it out of me.

In 1976, your father, a cop, was off duty when he was shot and killed in a bar during a robbery. Considering that he put you in a trash can and he threatened to kill you if he ever heard you were with a guy, did any part of you feel relief at his being gone?

I regret that I have to say yes. I have come to terms with the love I have for my father, but I would be a liar to say that I wasn’t relieved that he was gone.

I read an early profile of you when you were directing your first film, Shadowboxer. You were at a party in Bryn Mawr, at the mansion of one of the film’s financiers, and the writer noted that you were the only person of color and the only gay person in the whole crowd. Did you spend a lot of time in situations like that?

Yeah.

Was that lonely, or did you actually enjoy it?

It was great. You know, God really blessed me when I went to that all-white school. I never experienced racism. I didn’t experience racism until way into my adulthood. And then when I experienced it, because of the trash-can experience, I compartmentalized. I pretended it didn’t exist.

When you hung out in a house like that, you never suspected that even though those people were nice to you and gave you money for your film, they might be racists in their hearts?

They weren’t. They wouldn’t have given me money. They really trusted me. Or I was too fucked up, because at that time I think I was probably high; it was my drug years. But most of the financiers that have supported my mission so far have been white.

There was a period early in your career when you were managing actors. You said you managed one black actress whom you took to be as talented as Meryl Streep but who never got her due.

Paula Kelly. She was our Meryl Streep. But there were not opportunities for her. There were several black Meryl Streeps around.

Like who?

Oh my God. Phyllis Yvonne Stickney, Pearl Bailey. The real ka-banger was Dorothy Dandridge, who just didn’t get the opportunity. I got tired of telling people that there weren’t any jobs for them except pimps and drug dealers.

Do you think these actresses understood how different their careers might have been had they been white?

Oh, I can’t imagine their pain. It’s the reason I decided to produce, so I could give opportunities to black people that were not there.

Didn’t you represent Morgan Freeman for a period as well?

No. I didn’t. Well, a little bit, yes. For a moment. And what a moment. Cynthia Robinson Oredugba, the first female black agent at William Morris, and I worked with him.

What happened?

I was high. I’ll leave it at that.

So it was nothing Morgan did. Was it something you did?

I did something. It was a moment. It had to do with chicken wings. I really don’t want to talk about it.

You’ve said you used to smoke a lot of crack but stopped. Did you hit a wall at some point?

I did. I wanted my life, you know? Bob Fosse was a real hero of mine, and I watched All That Jazz over and over again. I remember watching that film and calling Patti LaBelle early in the morning that night, a little high. Not a little high, a lot high. And she asked, “Do you know Jesus?” I said a prayer, and I think that was the end of my drugs.

When I was watching Fosse/Verdon, I actually thought about how you’ve said you idolized Fosse.

Can I tell you something? When I found out [FX was] doing [Fosse/Verdon], I cried like a baby. Because I felt like, Why didn’t I get these opportunities? They know that I really wanted to do it. But I’m doing Sammy Davis Jr., the same sort of vein as that. But to me, Fosse is an idol, idol, idol.

Fosse famously had a drug problem. And he had great success but was forever miserable and unsatisfied, just as you’ve often said you are. He dropped dead at 60. You’re 59. Does it give you any perspective?

But I’m not miserable. I’m angsty and I’m sober, so that is really weird to be going to the Met Ball and to other social activities not intoxicated. I hate fucking being sober. It’s a bore. It’s a fucking snooze.

You don’t drink, either?

I don’t do anything. It’s really hard, but believe me, I’ve done enough for everybody. I never really even liked to drink, but I drank because my father told me if he ever saw me with a man he would kill me. And until I was 22, I had to get drunk to actually go through with the process. And then the drug scene came. And then all your friends start dying of AIDS. Not one, not two, not three, I’m talking intimate friends that you’ve had sex with, you’ve had dreams with, hopes with, people that are better souls than you, gone. And you can’t figure out, Why the fuck am I still here? So then it was like me on drugs and drinking, not even knowing I was an addict but just erasing all the pain.

I have to tell you, I’ve always been a little ambivalent about the famous Halle Berry–Billy Bob Thornton sex scene in Monster’s Ball, which you produced. I Googled it and see you can now watch it on YouPorn and a bunch of other porn-streaming sites. It’s obviously erotic, but I also wonder if there isn’t something exploitative about it.

To me, part of cinema is shock. You have to elicit erotic feelings, you have to elicit laughter, you have to elicit the sadness. You have to feel the human condition. And I remember feeling a lot of fucking men and women were uncomfortable. But a lot of babies were made that night, I bet.

Was the scene as written as raw as it was onscreen?

Not really. But why you got to ask me a question like that?

I’m honestly just curious. I let curiosity be my guide.

You’re trying to set me up.

No! I’m definitely not trying to set you up.

What is so shocking about two people, white or black, in such pain that the only way you can ease that pain is through sex?

Well, it’s a black woman having graphic sex with a racist white man. It’s a pretty shocking scene.

I can only talk about me, you know, me as a man, where I’ve been in my life. And how troubled I have been and how deeply I’ve compartmentalized some of this pain and trauma through drugs or sex. I don’t understand why you don’t understand that.

I was just thinking about Halle Berry. She won an Oscar — it was very emotional, she thanked Dorothy Dandridge — and then kind of disappeared. I just wondered if she ultimately lost some respect in Hollywood because of that scene.

She’s worked nonstop. She has a huge movie coming out, John Wick.

You’re right. She has worked a lot but mostly in genre stuff — horror and action.

I don’t know, I think that people choose their own paths; everyone has their own trajectory. No, the scene wasn’t written that way. A lot of scenes aren’t written the way you see them ultimately. She got the Oscar because she performed something that was so magnificent that we had never seen anything like it before. But I don’t think she got the Oscar for that scene. She got the Oscar for the beginning of that scene, the pain that she was in. We wanted to explore the pain. At least for me, I explore pain through sex, you know? When I’m in pain, that’s the only thing that sort of did it for me.

A few years ago, Angela Bassett said she turned down the role “because it’s such a stereotype about black women and sexuality.” You don’t think she had a point?

I’m really good friends with Angela, so I’m going to call her and find out because I never read that. I’m best friends with her, so I gotta ask her the hell was that about.

You once said you cast Berry for the role because, in your words, “that bitch can get us on Oprah.” That quote struck me as representing the soul of a true producer.

Yeah. It’s a showman. I grew up around hustlers. Part of that hustle was hustling the money for my art.

You are known for being really good at getting people to give you money for movies. How do you do that?

You tell them, “This is what I’m doing. This is what you’re going to get back. Do you believe in me? Here’s the script. Here are the actors. Please give me the money.” It’s pretty simple. I mean, you’ve got to kiss a lot of frogs before you find a prince.

Sharon Pinkenson, Greater Philadelphia Film Office head, once said she remembered on The Woodsman how many times she heard you basically just demand money from people.

Yeah.

People respond to that?

I’m not threatening. I think people can see my heart. People know there’s no cloak and mirrors.

I’m not sure if you were just being dramatic, but not long ago you said, in order to raise money for Monster’s Ball, you had to go to “the street” and suggested if you hadn’t paid the money back, something violent could have happened to you.

Easily.

What could have happened?

I could have been killed.

Who might have killed you?

Never mind that.

But they told you they would?

They didn’t have to because I’ve been very blessed to pay my debts off.

Last summer, Damon Dash, who invested in your early films, approached you at a Diana Ross show, and as she was singing “Reach Out and Touch,” he started telling you he wants his $2 million back, while someone with him filmed the whole thing. That’s kind of awkward.

I mean, you do what you’ve got to do.

Did you feel threatened?

Not at all. I’ve been in worse scenarios. But I learned a really valuable lesson from that. We may have a law, but the law that created me is a different law. Do you know what I mean? It’s a different kind of Hollywood law.

In an interview, you said that, under “white law,” he’d signed all the papers and the movie lost money and you didn’t owe him anything, but that, under “black law,” you had to pay your debt.

All I can tell you is it’s behind us, and I’m really happy he gave me the money, because if he didn’t, then I wouldn’t be where I’m at right now, talking to you. He believed in me when many people didn’t.

When Shadowboxer came out in 2005, it was savaged by critics. That must have been shattering. Did it make it more difficult for you to have the will to direct again?

That’s for sure. I remember coming back from [the Toronto International Film Festival] and my driver left the New York Post in the back seat for me to read. And it had a picture of Helen Mirren and Cuba Gooding Jr., saying, “The Worst Movie of the Century.” I thought that was the meanest thing ever. I fired him. But I knew that many people, and many, many, many black people, loved that film. We didn’t have the right marketing team, but it was ghetto fabulous at a time that I didn’t understand what ghetto fabulous even was. And though it’s not a perfect film, I think you see spurts of where I was going as a filmmaker. If I had been European, it would’ve been hailed as, you know, something special.

You followed it with Precious. I gather it was received differently by audiences at Sundance than by those at Magic Johnson in Harlem, where it was screen-tested.

It played at the Magic Johnson Theater like a comedy. But when we showed it at Sundance, it was a completely different reaction. I was like, Oh man, are they bored? And then at the end, they stood up. Barbara Bush sent me a personal letter saying, “Precious is my movie,” and we became friendly. I was just so blown away. I watch Precious and I laugh.

Seriously?

I do. I haven’t seen it in years, but I just hollered from beginning to end. Because that’s what we do.

It’s so brutal and sad. Laughing’s an appropriate reaction to that movie?

No, it’s not. It’s more like, Oh my God. Someone’s telling our secrets. Are you really, really going to go there? I think that those who have been abused and lived that life laugh. It’s so painful that you have to laugh. Because if you sit with it, you’ll fucking be in a mental institution.

In a way, Precious reminds me of Chris Rock’s classic bit about how nobody hates behavior they see in black communities more than other black people. In the same way, I feel like white audiences could glom onto certain pejorative things about black culture from Precious and see a kind of license to have negative thoughts. It’s like the inverse of the Huxtables, and it seems a little dangerous.

I felt like that. Let me tell you something: When they finally pulled me out of that edit room, I felt that I shouldn’t have done it. It was like I was buck naked on the toilet and everybody was watching me. That movie was that personal and that deep, and it was almost a spiritual awakening in me that I said, “No one should see this movie.” It was my soul. It was me.

The Weinstein Company released The Butler. Did you ever see anything that seemed inappropriate with Harvey?

Here’s the thing with Harvey: I dug Harvey. I knew what I was walking into. I told Harvey, “Do not fuck with me, because I don’t want to end up in the New York Post looking like a crazed animal fighting you.” So we had mutual respect for each other.

By “Don’t fuck with me,” did you mean don’t fuck with my movie? He’s known as “Harvey Scissorhands.”

Don’t touch my movie. And he didn’t. And unlike many other people, I got every penny that I’m owed from him.

The Butler was the kind of movie sometimes referred to as “Oscar bait.” I don’t understand how it got shut out of Academy Award nominations when Harvey was considered the magician of Oscar season.

First of all, who cares?

About awards? C’mon.

If you want to talk about awards, I didn’t complain when nobody was nominated in Empire. Terrence and Taraji [P. Henson]? We’re talking about fucking Brando and Streep.

But I saw your Instagram post about the Emmys when Empire wasn’t nominated after season one.

What did I say?

Jussie’s on the video saying you have to be nice, but then you say, “Fuck these motherfuckers.”

Sometimes I care, and sometimes I don’t. Sometimes I get angry. I think in my heart I really don’t care, because I know at the end of the day the work will live on forever.

When you were nominated for Best Director for Precious, Barbra Streisand presented the award and made a big deal about how the Oscar might be going to the first female, Kathryn Bigelow, or you, the first black Best Director. Then Bigelow won it. I wondered if you made The Butler to get that Oscar.

I’m not driven to be the first black person to win that Oscar. Was I disappointed? Yeah. Was I surprised? No. Oprah and Forest [Whitaker] got nods at the SAG Awards, and it was good enough for me. Then that whole he-should-have-been-nominated thing started. Everybody kept saying black people deserve it. I don’t think I deserve anything. My path has opened the door for this whole renaissance that is happening.

The Butler was in 2014. #OscarsSoWhite, of which you were vocally critical, came a year later. That year, all 20 actors nominated in acting categories were white, which hadn’t happened since 1998. Will Smith, Jada Pinkett Smith, and Spike Lee all boycotted the Oscars. It seemed like a reasonable thing to be upset about. Did you just think there was no black actor deserving of a nomination?

That’s a loaded question. It wasn’t that I was anti-#OscarSoWhite; I just thought it was being handled all wrong. I was on the board and worked to actually get a diverse group of people into the Academy to vote.

After directing Oprah in The Butler, you told the Telegraph, “Here’s how I talk to her: ‘Shut up and say the line. Just say it. That’s fake. You suck’ … She’s used to being in control, so it was liberating for her.” That made a few headlines, and I wondered if she reached out and said that kind of stuff was cool to say within the safety of the set but not so much in print.

We’re very good friends. The way you say that sounds disrespectful. It wasn’t said with the disrespectful tone you just said to me.

Did you ever think she was seriously considering running for president?

I begged her to! I was adamant. I’m sure I was one of many people doing it. And then she stopped texting me. Then I left her alone.

The Butler was famous for having 41 producers.

Whatever it takes.

The Hollywood Reporter ran a story that said this was evidence that movies about black subjects are difficult to finance. Is that true?

It is accurate. Well, at that time it was accurate. Now it seems there’s some white guilt going on that’s making some very untalented people famous. Right now everybody’s trying to make up for what they justifiably should be making up for.

You seem to be referencing something specific.

I’m referencing many somethings.

Spike Lee was obviously pissed that Green Book won the Best Picture Oscar. Did you feel the same?

I loved Green Book. I used to manage the writer, Nick Vallelonga, but I couldn’t find him a job. He wanted me to direct it, but he [was unable to get in touch with] me. Unbeknownst to me, he not only wanted me to direct the movie but to star in it. I’d never even known about it. He’s that crazy. I could never act. He wanted me to star as the gay guy.

There was a great deal of anger about that picture that I never quite understood. It felt like a generational issue.

Guess what? Build a bridge. Get the fuck over it. It’s a movie. We ain’t killing motherfuckers. I think they were making too much of it.

The criticism was that it was a black story basically turned by white writers into a white-savior story.

Here’s the thing: Mahershala Ali is as black as they come. As a black man, he would never have stepped into a place that wasn’t safe as an artist. And that’s what people are forgetting.

It’s a topic you have expressed strong opinions about. It got very awkward at a 2015 roundtable of showrunners that you participated in for The Hollywood Reporter.

It wasn’t awkward.

It seemed awkward.

It was awkward after. One guy was upset.

House of Cards’ Beau Willimon, right? He got very defensive when you asked each of the showrunners how many black people they had on their writing staffs.

I swear to God, that was not an attack. I wasn’t there to start a fight. I was just actually curious. Are you kidding me? I’m not that smart. I don’t know how to take on the white man.

You said at the roundtable, “Black people hate white people writing for black people. It’s so offensive.” But Danny Strong, who co-created Empire and wrote The Butler, is white.

I didn’t get writing credit on The Butler, but a lot of scenes were written by me. As a director, I don’t get credit on the writing. You just take that story and you got to make it yours. You cannot understand the African-American experience unless you are African-American. You can’t. I had to make the situations mine.

And Ilene Chaiken, the original showrunner on Empire, is white too.

Ilene did a marvelous job with an incredible group of African-American voices. What I loved about Ilene was that she knew what she didn’t know. She surrounded herself with people that were of the culture. And she deferred to me when it came to anything about the show.

In a recent interview, you said you’re going to get back into the Empire writers’ room and “fuck shit up.” Does that mean you’ve been disappointed?

A couple years ago, I was terribly disappointed. I thought it was not good.

Was there a particular moment you wanted to throw the remote at the TV?

I think maybe the third episode in the first season. I’d directed the pilot and the first episode, and then I handed it off to [Chaiken], who’s really a great director. But it wasn’t my look. There were things with Cookie’s hair, with lines that didn’t feel right. And I just said, “Oh my God, what the fuck is this?” Because I’m so fanatical about what I want you to see onscreen.

I have to tell you, in the more shocking scenes in your films, I’ve wondered what your mom must think watching them.

My mother’s a very churchgoing Christian. I remember the first movie I took her and my aunt to was John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, because part of John lives in me.

That’s the one in which Divine eats real dog shit.

Yeah, and I said, “Ma, you’ve got to go see this movie.” And my aunt slapped the shit out of me. “What the fuck did you take me to see this shit for?” So my mother got a taste of what was in my head at an early age. I think she was a little embarrassed about my work; not embarrassed but just like people at the church were giving her side-eye: “What happens in your house that your son is creating these worlds?” I really reached the pinnacle with Precious and The Paperboy. So she’s literally like, “Can you just shut these women up?” I don’t think Precious would be allowed to be made now. I don’t even know how it would be received. We used retard, we used Mongoloid.

Yes, hearing Precious’s baby called “Mongo” is pretty shocking. Didn’t your mother say, “Why can’t you make movies like Tyler Perry?” It’s a very Jewish-mother thing to say.

She did. She loves Tyler Perry. I really did The Butler for her. It took everything I had to restrain myself to do that PG-13 film. It felt like I was handcuffed. I did The Butler to shut my mother up and to show people that I can play buttoned-up if I have to. I can keep the camera still. It’s fucking like watching molasses dry, but I can.

Your movies can be pretty raw. Just a few minutes into Shadowboxer, a mobster shoves a broken pool cue into a guy’s ass. And then in The Paperboy, you have not only the famous scene where Nicole Kidman pees on Zac Efron, but also a very graphic one in which she has this kind of telepathic sex in jail with John Cusack in front of a bunch of guys.

You know what it was like to get her to do that?

I can’t imagine.

It’s no different than getting money from people. It’s trust. And when you have somebody’s trust, when you’ve got these fucking billionaires trusting you, it’s the most beautiful thing in the fucking world. And guess what? I said, “Nic, you trust me so bad, I’m going to give you everything I have.” And she got a SAG nomination for it, too. She deserved more, but I don’t think people saw that film.

I’m curious about what it was like to take Precious to Cannes, where it was adored, and then The Paperboy.

Well, let me just tell you something. They lied that they booed Paperboy in Cannes. It was a 23-minute standing ovation.

I’d certainly read that it was booed.

I’m telling you, I think the New York Times ran with a piece that was written by a blog that really hated me.

But getting booed doesn’t necessarily mean failure at Cannes. Wild at Heart was booed and then got the Palme d’Or. I personally cannot imagine putting myself emotionally in a situation where people would feel it appropriate to boo something I’d created with me sitting there. That’s just so twisted, isn’t it?

Yeah, and I didn’t hear a boo at all. It was a 15-minute standing ovation. Those two experiences at Cannes were probably the most emotional, the most exciting moments of my life, other than getting my two kids. It’s out-of-body. You leave the theater, you go outside, you start crying. You throw up, you go back in the theater, they’re still clapping for you, and you got vomit on your fucking tux. It’s better than any award, that’s for sure. It’s better than any high that I’ve ever fucking been on.

What’s it like if you get a standing ovation and then read that the film was booed?

Yeah, that was really fucking painful, man. That was a sabotaging thing. I don’t even want to go into it, but I think there were some people that were out for me and wanted to put the lid on it. Because I was a little ahead of the time, ahead of the curve. I’m always ahead of the curve.

*This article appears in the June 10, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo’, a satire that imagines the entire African-American population taking advantage of a free one-way flight to Africa. All in the Family’s fifth episode, from February 1971, introduces an effeminate character named Roger, who wears glasses. Archie Bunker states, “I never said a guy who wears glasses is a queer. A guy who wears glasses is a four-eyes. A guy who’s a fag is a queer.” Daniels and stylist Jahil Fisher have been a couple since 2011. In 1996, Daniels adopted his own niece and nephew, Clara and Liam, with his then-partner, casting director Billy Hopkins. The day of the supposed attack, Daniels posted an Instagram video, saying, “You didn’t deserve … to have a noose put around your neck, to have bleach thrown on you, to be called ‘die fucking nigger’ or whatever they said to you.” Howard writes in an invented language called “Terryology,” according a 2015 Rolling Stone profile. “He wrote forward and backward, with both his right and left hands, sometimes using symbols he made up that look foreign, if not alien, to keep his ideas secret until they could be patented.” According to a 2001 police report, Howard punched his estranged wife, Lori McCommas, twice in the face after kicking in her front door. He pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct. Dancer, choreographer, and actress Paula Kelly had supporting roles in the films Sweet Charity, Soylent Green, and Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling. She was nominated for an Emmy for her role as even-keeled public defender Liz Williams on Night Court. Daniels once described the night in 2002 when Halle Berry won her Best Actress Oscar for Monster’s Ball: “She was like … ‘Big Daddy, you coming to the Vanity Fair party?’ … I had two hookers on the side of me with a crack pipe. I said, ‘I’ll see you there, baby. I’ll be there.’ And I had no intention of showing.” HBO passed on Daniels’s script for a biopic of Sammy Davis Jr. based on the biography by Will Haygood. Daniels now wants to make it into a miniseries. Damon Dash sued Daniels twice over the $2 million he invested in the Daniels-produced pedophile drama The Woodsman. Dash argued that Daniels owed him money from his more successful projects. They settled in 2018. Stephen Holden wrote that Shadowboxer, a thriller starring Helen Mirren and Cuba Gooding Jr., “is an extravagance that leaves you with your mouth hanging open — partly in admiration of its audacity and partly in disbelief at its preposterousness.” Precious won both the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award at 2009’s Sundance Film Festival, only the third time one film had taken both prizes. Rock says, “I love black people, but I hate niggas,” in his 1996 special, Bring the Pain. “Boy, I wish they’d let me join the Ku Klux Klan.” Rock retired the joke after the special: “Some people that were racist thought they had license” to use the N-word. “So I’m done with that routine.” No black filmmaker has won the Best Director Oscar. Before Daniels, John Singleton had been nominated in 1992 for Boyz n the Hood. Subsequent nominees: Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), Barry Jenkins (Moonlight), Jordan Peele (Get Out), and Spike Lee (BlacKkKlansman). Addressing #OscarsSoWhite in 2017, Halle Berry said that because no other black women had won the Best Actress Oscar since her 2002 win, the award “really meant nothing … I thought it meant something, but I think it meant nothing.” Sheila Johnson, the co-founder of BET (with her ex-husband, Robert), was one of the movie’s first backers, investing $2.7 million of the $30 million budget and helping persuade other wealthy African-American investors to do the same. Producer-director-writer Ilene Chaikin is best known for co-creating HBO’s The L-Word, which she based on her own experiences as a lesbian. She is also an executive producer of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a project she developed. Kidman once related Daniels’s preproduction request: “I want you to start eating,” he told her. “Don’t work out, start eating, and get some booty, because you don’t have any booty.” Telegraph film critic Robbie Collin described the reaction he witnessed at The Paperboy’s Cannes screening as a “cacophonous quarter-hour of jeering, squawking and mooing.”