Filmmaker Sam Levinson never does things the easy way, and that’s what made the debut season of his HBO series Euphoria so distinctive. Loosely based on a same-named Israeli series by Ron Leshna and Dafna Levin, and drawing on his own experiences with teenage drug addiction, Euphoria is a kaleidoscopic look at the lives of troubled, yearning teenagers on a journey of self-discovery that happens to involve tons of sex, drugs, and cathartic weeping.

The look and feel of the show are as superheated as adolescence itself. The colors are bold, the score and needle-drop songs are loud, and the camera rarely sits still when it can glide, swoop, whip-pan, or spiral. Every episode starts with a speedy prologue outlining the backstory of a recurring character shot, cut, and scored like a “previously on” recap of someone’s life. (Levinson wrote all eight episodes in the first season and directed five.) The medium-size town in which the tale is set was mainly built from scratch, the better to allow for expressionistic lighting and acrobatic visuals. You might call it too much if too-muchness wasn’t the whole point.

After the season finale, I talked to Levinson at length about building this world, raiding his own life experience, achieving those wild flourishes, and drawing on a lifetime’s worth of influences, from The Passion of Joan of Arc to My So-Called Life.

How do you decide what a scene or sequence is going to contain? Is the filmmaking written into the script? Do the images, sound, or music ever dictate what happens in the story?

We established early on that each scene ought to be an interpretation of reality or a representation of an emotional reality. I’m not interested in realism. I’m interested in an emotional realism. A question that Marcell Rev, our cinematographer, and Michael Grasley, our production designer, talked about a lot about is, “How can we create a world that reveals the hopes and wishes of the characters that exist within it?”

How did you answer that question?

It’s hard to explain, but we settled on an approach that takes into account all aspects of a given scene in terms of wardrobe, makeup, lighting, set design, and how they’re all going to work together to produce this non-realistic effect we’re after.

Early on, I had gone into HBO to discuss the look and feel of the show. I said to them, “I really want to build everything on soundstages.” There was this long, pregnant pause, and I could tell they were confused. And they said, “But it’s gritty. You mean you don’t want to be out there in the streets and locations, just up close and dirty?” I was like, “Not really, no.” I told them I wanted to design it all from scratch, so it all feels like an extension of the individuals and characters that populate this world.

How did they respond to that idea?

On the pilot, which was directed by Augustine Frizell, I think HBO was reluctant to allow us to do that to the fullest possible extent. So they let us build just Jules’s bedroom. We decided that set ought to be a nest, it ought to be cozy, it ought to exist outside of space and time. There should be no ability for any kind of harsh light to seep in. If you look at the last shot of the pilot, we start kind of far back, you see the two of them lying in bed, you see the ceiling, and slowly, our camera moves up and over them. The ceiling is actually just on hinges, [operated] with ropes, so that the ceiling could come off and the camera could get above them.

I’m sure you’re aware that some people criticize this show as being unrealistic. But it sounds as if realism isn’t at the top of your to-do list.

No. It holds zero interest to me, in so much as we’re talking about realism in a cinematic sense, in terms of the aesthetics and the look of the world. I know we get that criticism quite a bit. And yeah, it’s not real. Teenagers don’t do extravagant makeup like this, and so on. But at the same time, there’s people constantly saying how real the show feels, which creates an interesting paradox.

When things happen on the show that could probably never happen, or that probably wouldn’t happen in quite that way in real life, and people say, “That felt so real,” what are they saying to you?

That the emotional reality of it is connecting with them.

What about you? Did you feel a connection?

Yeah, very strongly, despite being an old, straight white guy who grew up in Texas in the ’70s and ’80s. This show gave me flashbacks to what it felt like to be a teenager. Every friendship is tight yet at the same time susceptible to being destroyed by stupid misunderstandings. And when you fall hard for somebody, you’re not just miserably obsessed — some part of you believes this is the last chance at love that you’ll have.

It all feels like life-or-death when you’re younger. It means a lot to hear you say that, because one of the big surprises of all this is how the audience turned out to be a lot broader than I think we were initially given credit for appealing to.

What’s the genesis of the project?

I tried to write a version of this when I was 21. I had just gotten clean a year or two earlier, after spending the majority of my teenage years on drugs and really battling addiction. I couldn’t write it then, and I tried again in my mid-20s and couldn’t write it then, either. I think I was having trouble because I hadn’t examined or addressed any underlying issues that led to that addiction. It was only when I got a little bit older and had a family and gained a certain amount of [filmmaking] ability that I unlocked the piece as a whole.

Can we talk about the show’s portrayal of addiction and drug use? It’s a major part of the show, along with the characters’ sex lives. Also, it seems as if you don’t draw any kind of dividing line between legal and illegal drugs, and I wanted to find out your thinking on that subject.

One thing I would say first is, I think Rue is the only person who is struggling with drug addiction. There are moments in which other characters experiment with drugs, but that’s a very different experience. As far as legal versus prescription drugs, from the perspective of Rue, she doesn’t really do a lot of other things other than pharmaceuticals. Sometimes I read [reviews] that say she’s doing cocaine and stuff like that. I always imagine that she’s crushing up benzos or opioids and snorting them. But I think Rue will do anything or take anything that she thinks might quiet the sounds in her head and in the world at large.

Is the look of the show in any way shaped by the heightened perceptions you feel when you’re doing drugs, or when you’re drunk, or having that dopamine rush from sex or intense emotion?

Maybe. Jules’s night out at the nightclub is influenced by the fact that she experiments with drugs. And then, obviously, there’s the opioid sequence where the room starts to rotate and Rue’s climbing the walls. But otherwise, in terms of our kind of movement and lensing and stuff, it’s pretty consistent. We shot the entire show with one lens, so it’s very consistent that way. But it’s more a general feeling of wanting it all to feel subjective.

I’d like to hear more about the rules you set down to achieve this aesthetic.

We weren’t too dogmatic about anything. But, for example, when the camera is moving, it’s always on tracks or on a dolly. We do very little handheld camerawork. And probably 70 percent of the show is shot on sets.

That’s a lot. Including the sequence at the fairgrounds?

Yeah, the fairgrounds, too. That was the first episode that we started shooting after we did the pilot. Marcell and I sat down with Peter Beck, our storyboard artist, and we basically storyboarded the entire episode. There were roughly 700 or 800 boards, and then, in conversation with [production director] Michael [Grasley], we built all the sets from those boards. The whole thing ended up being about 125,000 square feet.

We got rides from all over California and Arizona and brought them in and repositioned them and built them around our shots. We tried to be efficient with how we did it, so if we were laying 400 feet of dolly track, we would shoot a scene going one direction. Then we’d flip the dolly around and shoot the next scene looking in the opposite direction [at a different part of the set] so we didn’t have to lay track all over again. The whole thing took six days.

How do you know that all your bits and pieces are going to fit together? Do you do an animatic of the storyboards for an elaborate shot like the one at the carnival to create a kind of flip-book simulation of what it’ll look like when you actually go on the sets?

Not really. We don’t pre-visualize anything, except the [rotating] hallway in the pilot just for engineering purposes.

Do you know roughly how long each of the shots in a scene or sequence are going to be?

To a certain extent, yeah. I have a rough feeling of how long a particular shot or even a scene is going to last.

How do you guard against getting bogged down in the details and blowing your budget or your schedule?

Part of the nature of television is that it doesn’t usually allow for a lot of indulgence. You can’t really “go over” in any meaningful sense. We try to maintain a certain pace as we shoot because we know we’re working with a narrow margin [of error].

On this show, we made the decision in advance not to do a lot of coverage, which is unusual for television. But in deciding to shoot that way, we accepted the fact that we had to really plan the thing out to get it right.

That tracking shot in the carnival sequence lasts over two minutes and goes all over the place. Was that all one unbroken take, or was it done in pieces and stitched together digitally?

Not digital wizardry, just some very simple [transitions]. Initially, I had written a kind of montage of everybody getting ready for the carnival, and I felt like it just wasn’t interesting enough. I didn’t know what it was saying, and I wanted to start small and then burst out into this world with the same excitement that you have when the carnival comes to town and you’re young.

That [tracking shot] wasn’t really scripted, with the exception of the dialogue. Because we couldn’t see the carnival until it arrived, Marcell and I wandered around and basically designed the shot and [ultimately] moved a few of the rides because we wanted to make sure that we were going to be able to connect all of these characters in this space and then land close on Cal, the character who is propelling, in some larger sort of metaphorical way, the action of the episode.

Were you handing the camera from person to person like a hot potato?

Not totally! It just looks that way.

Can you me walk through that shot? It’s like a microcosm of the show.

We knew we wanted that shot to start inside of the pretzel stand. So we found this old, broken RV and we cut it in half so that we could put a crane arm through it and then push through after Fezco opens up the [front shutter]. As the camera pushes through and we pan with Fezco, we [quickly dissolve] with Fezco as he walks around the ticket booth and walks down the other side of the row of carnival booths.

So that first part of this long shot is actually two individual camera moves. And you’re doing that throughout — breaking a long shot into separate pieces and then “stitching” the pieces together in the editing room?

Basically, yeah. We did a stitch on that little ticket booth. If you had been on the set, you would have seen about 300 feet of dolly track [on the other side of the ticket booth]. When we were shooting that next part, we picked up his same movement again, and we made sure the framing was exact and that all the extras were in the same place between the two shots. Then we carried the shot all the way over to Maddy, and there’s another stitch right there because we had to move the camera off the dolly tracks and onto a TechnoCrane to get up and over to that Ferris Wheel.

Shots like that require a lot of coordination, and they’re a testament to our crew. Those were really difficult days to shoot, and they were the first things we did as a series, but I think the results are worth it.

If we see a flourish on the show that feels like a grace note, is that stuff also planned out and storyboarded? Or do you have the ability to improvise?

If you give me an example, I can probably tell you.

I have two, and they’re both from the pre-credits sequence from episode four, about Jules’s experiences as a child in a mental hospital. First, there’s this shot where you see her walking in the hallway, and this kind of theatrical spotlighting appears and follows her.

You also have a shot later in the sequence where she gets released from the hospital. You see her clipped-off bracelet lying on the bed, and then the camera moves to the window to reveal her embracing her mother in the parking lot.

Are moments like those written into the script and planned ahead of time, or is it possible to come up with them on the fly?

It depends on the scene. Both of the ones you mention happened to be storyboarded. Young Jules walking through the hallway was a shot that required a lot of advance planning and design, because we had to cut a strip out of the ceiling of our school hallway [set], put a [spotlight] above Young Jules that was on cables, and then basically walk that light along with Jules. That shot was about set construction, rigging, that kind of stuff.

The other scene you mention was originally just a shot through the window. But as we were shooting it, we realized we wanted to give the shot a bit of space and breathing room, and then the question became, “What are we looking at? How can we drive the scene forward emotionally in a way that gets us to that window?” So we put a clipped-off bracelet on the bed, and kind of piled up the sheets.

You have a lot more sex on this show than is typical for an American TV drama, and a lot of it involves teenage characters. Even though the actors are all older than that, you still have to worry about sensitive issues. What steps do you take to make sure that the actors aren’t being made uncomfortable for too long, or put in a situation where they’re doing something they don’t feel right about?

One, we have intimacy coordinators. But ultimately, I think it’s the same as any other aspect of filmmaking, which is that you want to make sure that the actors always feel supported and safe in their environment. That’s what allows for them to be as good as they can be and tap into the well of emotions that are necessary for really getting a scene. With sex scenes in particular, it’s extremely important for us as a crew to make sure that we know exactly what our camera movement is and make sure that everything is rehearsed so we can get it done as fast as possible. Age aside, it’s not particularly comfortable for anybody to shoot a sex scene because it’s awkward.

Despite the amount of movement that we put into the series as a whole, I thought it was important to have moments in the sex scenes where the camera is still and we’re getting a sense of what the characters are thinking and feeling. At those moments, you want the camera to be, not objective exactly, but to allow for the discomfort and nervousness you feel when you’re having sex as a young person, for all those emotional aspects to be apparent to the viewer. And you can’t do that if every shot has a sheen to it.

Who are your guiding lights when you’re working in this show?

A big one is Carl Dreyer, just in terms of how he shot close-ups. You know those low-angle close-ups of characters looking up, those passionate close-ups, where you feel like you’re sort of breathing with the characters? The Passion of Joan of Arc is a big one, obviously.

There’s a Hungarian film called Time Stands Still, by Péter Gothár, that was a big influence on us, just in terms of dealing with young people and lighting them and creating a mood. And Francis Coppola’s One From the Heart, in terms of world-building, and because there was an experimental aspect to what he was trying to pull off, shooting everything on sets. And of course, early Paul Thomas Anderson, particularly Boogie Nights and Magnolia. More so Magnolia, in terms of its camera movement and the love and empathy he displays for all those characters.

In my notes on the carnival episode, I actually wrote, “Paul Thomas Anderson’s My So-Called Life.”

Exactly!

Don’t you specifically name-check that show in Euphoria?

Yeah, we do, in episode three.

What is the importance of My So-Called Life for you personally and for Euphoria?

Winnie Holzman’s show was the first television show I watched when I was younger where I felt like I was watching myself, just in terms of Angela’s insecurities and the things she’s thinking about, the free-wheeling nature of her ideas and thoughts. It really, deeply affected me. I revisited that show a number of times because there’s a sensitivity and humanity in it that’s incredibly rare.

I don’t mean to turn this into a My So-Called Life geek-out, but—

No, go ahead!

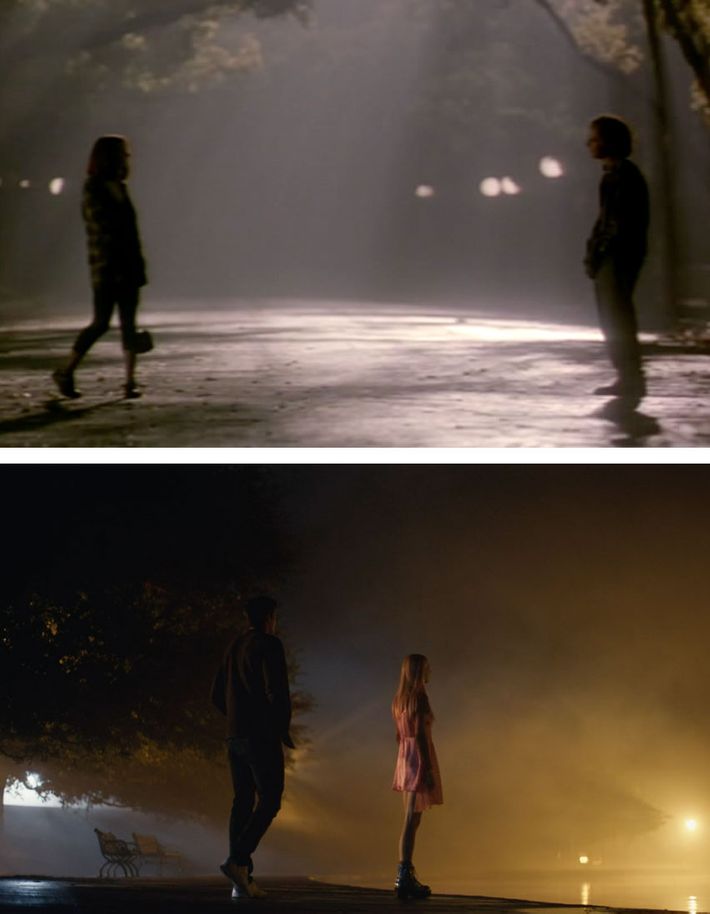

There’s a moment near the end of the My So-Called Life pilot where Brian Krakow and Angela are in the street at night, and the REM song “Everybody Hurts” is playing. There’s something about the look and feel of that scene, with the light streaming down the trees, that looks like certain scenes on your show.

That was a great scene, and I’m sure it had an impact on me. You know, My So-Called Life was a bold show cinematically, and I don’t think it was ever given credit for that at the time. The camera moves above a classroom and goes over a light at one point! In a lot of our night exteriors, we drew on their style of photography, which captures how the world feels a little dangerous and unsettling and big and when you’re young and sneaking out and wandering around. The backlighting of the trees, the light streaming out. It’s just beautiful. It’s hard for me to express how much that show meant to me.