Chapter One: A Baffling Question

Who is Nancy Drew? At the New York Public Library, she is filed under “Women Detectives” and “Action and Adventure Fiction” and “Code and Cipher Stories.” If you are the target demo of a Drew book — tween, female, and solitary enough to spend time reading — she is the antidote to a life full of mysteries with unsatisfying conclusions. (Why are girls at school mean to me? Why do I bleed from the crotch every month?) If you are a woman who has aged out of that demo, she is nostalgia. If you are in sales at Penguin Random House, she is a cash cow. (The original Nancy Drew books still sell more than 350,000 copies a year. And there are over 70 million of the books in print — a number that includes both the classics and their spinoffs.) If you are a network executive, she is marketable intellectual property. If you are a male, she is — wait, who?

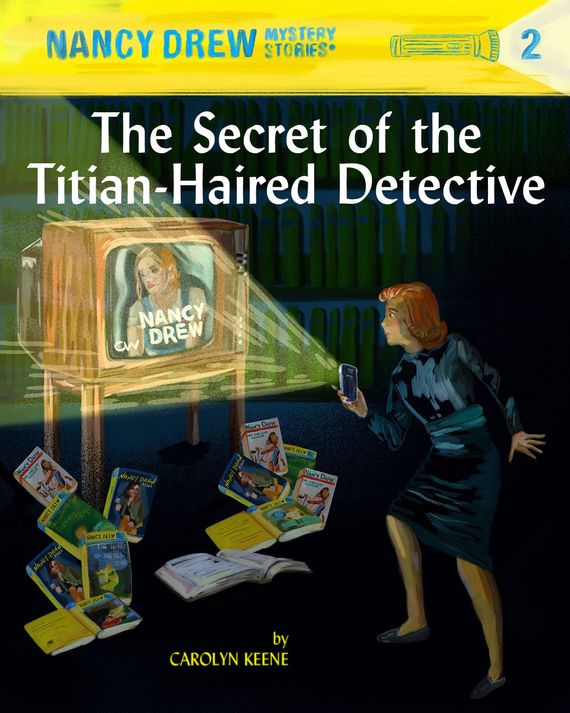

If you are me, Nancy Drew is the first thing you collected, meaning the first thing I desired with completist gluttony and could, at $2 a pop from the local used-book store, afford. The Nancy Drew Mystery Stories were designed for bulk acquisition. Lined up on a shelf, the yellow spines formed a banana slug of escape opportunities. I would describe them less as novels than as “fodder.” I liked the way Nancy looked on the covers, which was tastefully made-up and inquisitive, and I liked sniffing the pages, which smelled like stamp glue.

The conventions of the series were stable. Nancy, an amateur sleuth, was customarily described somewhere in the first few pages as “titian-haired” — a phrase that no child in recent centuries has read without confusion — before stumbling into a mystery and becoming obsessed with it. The mysteries generally turned on something like a phantom horse or Indian amulet or set of purloined African documents, and they relied on line breaks and exclamation points for narrative velocity.

Like this!

Nancy drove a sporty blue car. She courted danger. She got knocked down, and she got up again. (Literally: A lot of the books have Nancy losing consciousness at a vital moment, like one of those fainting goats.) She solved the mystery. Her bravery was applauded. Along the way, she interacted with her boyfriend, Ned Nickerson, who made passive-aggressive comments about the way his girlfriend was always doggedly pursuing clues instead of him, and hung out with her best friends, George and Bess. Of all the characters, George is the most futuristically out of place in the original books: She is inevitably described as boyish and handsome with short hair and a taste for athletic competitions. I’m not alleging that the series’ pseudonymous author, Carolyn Keene, planted a crypto-lesbian in her detective tales, but I’m not alleging she didn’t.

The first volume came out in 1930, written by Mildred Wirt Benson from an idea devised by an author named Edward Stratemeyer. Stratemeyer ran a syndicate that originated nearly 1,400 books, including the Bobbsey Twins and the Hardy Boys. He came up with plot ideas, wrote three-page outlines, and distributed them to staff writers who fleshed out the books at warp speed for a flat fee of $50 to $250 per title. Like all of the books that followed, the first Nancy Drew was published under the Carolyn Keene pen name.

By the late 1930s, the series was so popular that it had been translated into Braille. By 1969, more than 30 million copies had been sold. Revised editions of the core 64 titles have been released over the decades with the covers evolving — Nancy in a flapper outfit transitions to Nancy in jeans — and questionable elements of the originals, like racism, edited out. Nancy’s personality has been tweaked, too; in the perfect words of some anonymous Wikipedia editor, she has become “less unruly and violent” with the passage of time — a curious reversal of the trend in which heroines are increasingly as bloodthirsty as their male counterparts. By now, there are multiple movie and TV adaptations, and book translations into Vietnamese and Icelandic, and there is the possibility of purchasing a shirt that says “I’M NOT SAYING I’M NANCY DREW. I’M JUST SAYING THAT NOBODY HAS EVER SEEN ME AND NANCY DREW IN THE SAME ROOM.”

Like any morsel of profitable IP, Nancy is both a constellation of specific traits (red hair, sporty blue car) and a neutral substrate that can be topped, toastlike, with whatever condiment the decade requires: margarine in the 1930s, avocado in 2019. In a 1970s TV adaptation, Nancy wore slinky halter tops and had feathered hair. Scott Speedman played Nancy’s boyfriend in the 1995 version. (Lucky.) A company called HeR Interactive spun out a bunch of Nancy Drew computer games starting in the late ’90s. (The company’s tagline, possibly the apex of gaming sloganeering: “For girls who aren’t afraid of a mouse.”) Nancy reappeared in 2002 on TV, then in a 2007 movie with Emma Roberts. A Nancy Drew movie released earlier this year replaced Nancy’s car with a skateboard. (She wore a helmet.)

The newest onscreen version of Nancy, who appears in a CW TV adaptation this fall, is noticeably sex-positive: Within four minutes of the pilot’s start, she’s fucking Ned Nickerson’s brains out. Whoa! The most appealing character on the adaptation is George, whom the CW show turns into a cynical bitch with Amy Winehouse eyeliner and tattoos. She manages the restaurant where both girls work, has all of the show’s funniest lines, is ethnically ambiguous, and has a boy’s name. George is cool, in other words, and Nancy, stuck halfway between 1950 and the 21st century, is a dork. A likable dork, but still. If the show weren’t tethered to its IP, George would be the obvious starring character.

I’ve seen nothing more than that pilot, so I can’t speak to Nancy’s development over the series, but the coitus looks like more of a flourish than a theme. Like Old Nancy, New Nancy is a human glass of whole milk: nutritious, passé, white. (Somehow she has sex fully clothed.) In her early days, Nancy offered a well-mannered mold for Truman-era parents to pour their messy girl children into. But if genre novels are big brimming bowls of escapism, then what kind of escape does a squeaky-clean type-A heroine like Nancy have to offer? Isn’t she exactly the sort of mannered do-gooder who repulses any human in the prepubertal range?

Chapter Two: A Tangled Trail

Young readers have historically been drawn to two opposing female character types. On the one hand, they like characters who push juvenile traits to their screechiest, id-iest extreme and get away with it. In this category, we have the mischievous heroine (Ramona Quimby), the spirited heroine (Anne of Green Gables), the naughty (Eloise), and the anarchic (Pippi Longstocking). It’s a gleefully simple form of wish fulfillment: the idea that an untrammeled kid could bend the rest of the world to her will without ever bothering to brush her teeth or use an indoor voice — a daydream about growing older without having to change.

The opposing type of character is the adult-in-a-kid’s-body — both an aspirational and a fantastical model of being. Many young people, it turns out, don’t conceive of themselves as a lesser class of dumber, smaller humans, and this constituency enjoys books that mirror their delusion — and so we have the philosophical heroine (Turtle Wexler from The Westing Game), the stoic heroine (Claudia from The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler), the intellectual (Roald Dahl’s Matilda), the careerist (Harriet the Spy), the neurotic (Anastasia Krupnik), and, of course, Nancy, who resembles no youth ever to traipse the Earth.

Most of the Nancy Drew readers I’ve talked to have two things in common: fond memories of the books and an amnesiac inability to remember anything about them. My explanation for this is that Nancy is an incredibly boring character. It’s not an original observation. Writing in 1975, Karla Ruskin pointed out that the detective’s most exceptional trait is her lack of exceptional traits. “Nancy is not ‘different,’ a quality as highly prized as leprosy when you’re young,” Ruskin wrote. “There is no magic to her, no eccentricity, no humor. She is simply prettier (but not a raving beauty), brighter (but not a crazy genius) and nicer than most people.” Mid-century modest. If Nancy were perfect in the approved contemporary way — in the way that, for example, Gwyneth Paltrow is perfect — she’d be funnier and more self-aware, with a collection of minor vulnerabilities to trot out as exceptions proving the rule of her ecru-colored flawlessness. Instead of freelancing for her dad, she’d establish a detective start-up of her own. She would build a personal brand. She would start, for God’s sake, accepting money for her work. Instead, Nancy has leaned so far out she’s practically prone on the floor.

But it was never Nancy’s personality that shone; it was her skills. I reread The Mystery of the Ivory Charm, the 13th installment of the original series, to revisit the redheaded gumshoe as she appeared in print, unimpeded by the doughnut glaze of my nostalgia. On the cover is our protagonist, stiffly coiffed and with a menacing brown-skinned man in a turban floating behind her (an accurate snapshot of the series’, uh, racial politics). Inside the book, Nancy rescues a helpless child, assists with housework, climbs a rope, dresses injuries, hides in a clump of bushes, confirms suspicions, obeys the law, thwarts bad guys, and zips up the case. She is polite and well groomed. Her hunches are infallible. She says things like, “For a long while I have suspected the truth — now I am certain of it.”

The Nancy Drew books make a case that you can be a complete nonentity — okay, a privileged nonentity — and still do tons of courageous, adventurous, altruistic stuff. Her glamour isn’t to be found in her adjectives — tactful, cordial, serious — but in her verbs. She’s constantly jumping, springing, racing, clambering, scrambling, darting after shadowy crooks, and zooming away in the blue convertible. One thing the CW show does get right is the character’s mobility — in the pilot, at least, she doesn’t drive a car, but she does pop up immediately after having sex with Ned Nickerson and sprints away.

At the initial age of Drew consumption, my definition of “freedom” was pretty elementary. Freedom was the ability to leave the house, roam unobserved, and return safely when I felt like it to a stocked pantry. This is what all kids would do starting at age 7 if they didn’t have parents to stop them. Bursts of elective chaos with a cozy ending are what the Nancy Drew books deliver. A shot of endangerment with a chaser of domesticity. The plots might be spooky, but they are never creepy.

It’s a strenuous mental exercise to rewind to a time when basic capability wasn’t assumed in young women, but you have to force yourself to do it when you peer back at Nancy Drew. Readers in the 1950s would have experienced her usefulness and abilities as subversive. They would have marveled at all the public credit given to her triumphs, even if she inevitably refused to accept it. Identifying with Nancy was a way for girls to feel unburdened — not just physically, in space and time and miles per hour, but by expectations. After all, she was twice as accomplished as her male counterparts. (There were two Hardy Boys!) She had money, family, friends, adventure, a fulfilling career, and a slim figure. Nancy Drew, who is technically 55 years older than Sheryl Sandberg, was maybe the first unrealistic “have it all” heroine.

Chapter Three: The One-Way Street

So far, none of the attempts to translate Nancy into TV or movie form have been as lucrative as the book sales would suggest. Perhaps it’s because in an age when every girlboss is expected to #slay, much of what once made the sleuth provocative has evaporated.

Another possibility: Part of the pleasure of revisiting childhood books is discovering all the ways in which they reflect favorably on your younger self. What a cool and interesting kid I was for liking this!, you think, paging through The Westing Game or Sideways Stories From Wayside School. Rereading Nancy Drew is, I’m sorry to say it, an unflattering experience. As I worked through chapters about visiting a circus (“An Angry Elephant”) and discovering a hidden rock door (“Hidden Rock Door”) and pursuing a suspect off a bridge into roiling waters (“Dangerous Dive”), my inner monologue ran more like, “I must have been incredibly lame and dimwitted to find this compelling.”

But discovering the mediocrity of a beloved childhood book doesn’t always mean that the book was bad or the reader was lame. Sometimes it means that the book served its purpose: It turned you into an adult capable of distinguishing between great and not-great books. With their candylike covers and porridgelike plots, the books pushed me and others further down the trail to better reading material. Nancy Drew, unlike Eloise or Pippi Longstocking, has proved to be a one-way street. Rereading Carolyn Keene when you’ve tasted Agatha Christie is like eating diet ice cream after years of Häagen-Dazs. It’s like reverting to the Counting Crows after you’ve locked into Van Morrison. Or snuggling up to some R.L. Stine when you’ve sipped on the sweet nectar of Stephen King. Maybe Nancy Drew is unrevivable. Maybe rebooting Nancy Drew is like … rebooting a training bra.