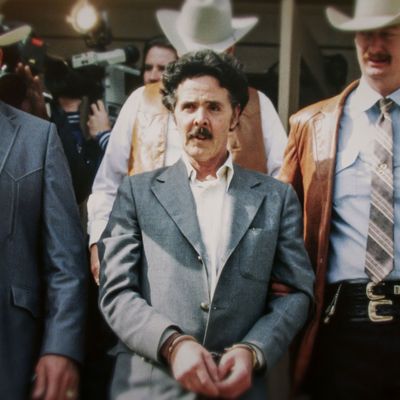

“What are we gonna do about these other 100 women I killed?” That’s how infamous serial killer Henry Lee Lucas kicked off a firestorm that ended with him confessing to 600 murders across the country, and with law enforcement closing 197 of those cases. Lucas posed that question to the judge during an arraignment for the murder of an elderly woman, Kate Rich, whom he and his 15-year-old girlfriend were hired to care for. He also killed the girl, Becky Powell, and had served time in prison for killing his own mother in 1960.

When Lucas started talking, the Texas Rangers formed a task force, led by Sheriff Jim Boutwell, a law-enforcement hero at the time, to handle the confessions and visits from other law-enforcement agencies who wanted to clear their unsolved cases. To keep the confessions flowing, the task force gave Lucas the star treatment, supplying him with all the cigarettes and strawberry milkshakes he wanted, and letting him traverse the jail without handcuffs. Often, they provided him with crime-scene photographs and other details related to the victims and the crime scenes, which Lucas used to take responsibility for the murders.

It all collapsed when an investigation by the Dallas Times Herald revealed that there was no way Lucas could have committed all those murders — sometimes he was even in the wrong state at the time. But Lucas was convicted of 11 murders and sentenced to death, though in 1998 his sentence was commuted by then-governor George W. Bush. Eventually, Lucas recanted his confessions and died in prison from congestive heart failure in 2001. Using DNA technology, law-enforcement officials have now closed at least 20 of the cases to which Lucas had confessed.

Netflix’s five-part docuseries The Confession Killer compellingly tells the story of how Lucas was both a serial killer and a serial liar, and, more importantly, explores law enforcement’s fixation with closing cases and the toll it takes on the families of the victims. While the police may not have set out to frame an innocent man, hundreds of actual murderers went free, capturing the interest of Taki Oldham, one of the documentary’s directors.

Oldham and co-director Robert Kenner, who was nominated for an Oscar for his documentary Food, Inc., began with a massive collection of old Lucas confessions and case files that a former investigator for Lucas’ defense was hoarding in a storage facility. They spoke with Vulture about the five-year journey to produce the docuseries and why they hope it compels law enforcement to reopen all of the unsolved cases.

How did you become interested in the story of Henry Lee Lucas and what made you want to re-examine this case?

Oldham: Back in 2014, I was channel surfing and came across a documentary hosted by Bill Kurtis [Myth of a Serial Killer: The Henry Lee Lucas Story] that finished with Kurtis posing the question that if Lucas didn’t kill those 200 people, who did, and how was the killer still walking free? It was around the time Lucas died and people thought it would forever remain a mystery. So I Googled “Henry Lee Lucas” and “DNA,” just those two terms, and sure enough, a couple of hits came up and other killers had been found and convicted in a couple of the cases that had been Lucas cases — one of which we feature in the series, the murders of Rita Salazar and Kevin Key.

From there, I went wow, maybe, there is the chance to tell a new chapter of this story. I fished around more and I got a list of cases and narrowed the search. Pretty quickly, I found 10 or 12 more cases where the same thing had happened. The real killer had been identified, usually by DNA, and Lucas had been cleared. Suddenly, what had been a he-said-she-said little dance had the potential to be answered. I spoke to Robby about it and we saw that it had the potential to be way more than just a normal true-crime story.

Kenner: I think what’s so interesting is Taki went back and saw these cases that were viewed in isolation. They weren’t thought to be part of an overall pattern, which is what interested us. Lucas didn’t do this and yet he’s considered the worst serial killer in all of history. How could this have happened? So we started looking at the myth and at the same time meeting the family members of victims so desperately seeking justice. It’s an amazing story with so many twists and turns. I wouldn’t have wanted to make a series about just a serial killer. Taki had something that was really a psychological tale of how everybody was getting from Henry what they wanted. And that was so fascinating. Taki had worked on it for a year and a half, then we worked on it for about a year and half, then Netflix came in and we spent another two years. So it’s five years of searching for material and finding people who would talk and trying to tell the story from every freaking angle that we could.

You found so many people who were involved in the Henry Lee Lucas cases: Rangers, lawyers, the journalists, the families, the spiritual advisor, and retired homicide detective Linda Erwin.

Kenner: That was an interesting story, because Taki called her a few times and she just hung up.

Oldham: Yeah, pretty much.

Kenner: And then I called her and I go, “Oh, we have a good friend in common.” And she goes, “Really?” And then I started to talk about the series and she said, “You’re trying to rope me in are you?” And she didn’t really want to talk.

Why not?

Kenner: Because she comes from a family of all law enforcement and she had nothing good to say about law enforcement for this particular case. It was very painful for her. But once we got her in the room, which took a lot of work, she couldn’t help herself because she thought things were done wrong. And she said there are times as a detective that you look at a case and you think you know who did it, but you don’t have the proof and you have to let it go. She goes, “It’s really hard to do, but you can’t convict because you have a feeling. It’s better to let the guilty man go than to convict an innocent man.” She was great. But that was not an easy get.

What do you think finally persuaded her to do it?

Kenner: Because there was an injustice and she couldn’t help herself. The more she thought about it, the more she felt she needed to talk. A part of it is the desire to go on the historical record. She didn’t want to speak badly of fellow officers, but she thought they made a mistake.

It’s one thing to make a mistake, but they made intentional decisions.

Kenner: This was a tricky thing for us in making a series, because I don’t think it was a conspiracy on their part. I think that these were people trying to do the best thing they could, but at a certain point, the journalists and other people started to point out problems with it and they got too invested in it. And on some level it becomes a cover-up, but I don’t think it started out that way.

Oldham: That’s a really important point. No one went into this with bad intentions. The other day I was watching something on the Milgram psychological experiment. Once people went past a certain point of the electrocutions, they were the ones who wanted to keep going to the end. It was an example of what happens sometimes when we realize we might be doing something wrong, or we might be making a mistake, and we double down because it’s really hard to pull back. This was one of those things where, if it wasn’t on such a large scale and there weren’t so many officers involved, then it might not have been able to happen. It’s an irony on that level just because we end up doing the wrong thing, it doesn’t mean we meant to do it in the first place.

I didn’t mean that it was something they set out to do from the beginning, but the officers did provide Henry with leading information so he would confess and close their cases. Certainly that’s intentional? Oldham: I would disagree. In their minds, if he killed 600 people, how was he going to remember everything? You need some hints. In their mind, they weren’t crossing the line.

Kenner: I think it’s a mistake that they didn’t catch but, at the same time, when they were presented by information from [journalist] Hugh Aynesworth, they weren’t ready to listen to it. They weren’t thinking they were feeding information to an innocent man. They assumed he was guilty.

Oldham: So they weren’t doing it in a way they felt was framing someone. But there were people who came along who just wanted to clear their books. Everyone had a different agenda and a different process.

Kenner: And the Rangers absolutely added credibility to these small-town police forces that came in. It led credibility to Lucas’s guilt. [Texas Ranger] Bob Prince defends himself saying, “We were just a clearing house. We didn’t know whether he was guilty or not.” But, in our minds, they added a certain credibility to his guilt, and these other people would then accept his confession. Obviously, he was also prepped for them and he got too much information. And they didn’t do it well.

This is why for us this is such an amazing story. This is more than just about a serial killer. It’s really a psychological tale. Henry is one of the most fascinating characters you’ll ever come across, but what’s so interesting is that he became what everyone was looking for. He was what Sheriff [Jim] Boutwell needed. He needed to find the serial killer. All these police departments needed to close cases to bring closure to the victims’ families. Ultimately, he became certainly what [jailhouse minister] Sister Clemmie [Schroeder] needed, because he found God. He brought comfort to the family members of the people supposedly he’d killed. We kind of believe Lucas believed everything he was saying to everybody. He just couldn’t tell what was right or wrong. And what’s so interesting is that everybody believed what he was saying because they wanted to believe it.

Do you think he eventually came to the understanding that he misled everyone? Did he get it?

Kenner: One of the most fascinating lines in the film is when someone says, “How did this happen?” And he said, “I don’t know, maybe the sheriff is responsible, or maybe it’s the Rangers, or maybe it’s me.” It’s a level of introspection you wouldn’t expect from Henry. At a certain point, he turned. I think he had a hard time continuing to keep confessing because he did keep saying to Aynesworth he didn’t do these things when he was confessing. I think Henry believed whatever he was saying at that moment.

What would you ask Sheriff Boutwell if you had had an opportunity?Kenner: The ultimate thing is every one of Boutwell’s cases is overturned, as well as other cases that don’t involve Lucas. There are even more horrific cases that don’t involve Lucas where Boutwell sent people to prison for life and really hid evidence. It’s bad. When we mentioned this to Bob Prince he said, “I only wish Boutwell were here to defend himself today.” And I’m thinking, “Yeah, but you know there’s absolute proof that Lucas didn’t do them.” In a way, Boutwell got to say what he needed to say.

But Boutwell is certainly a key character in the film. Boutwell was a totally respected lawman at the time. He was God in the country. He got to do what he wanted to do and he didn’t have to necessarily have to back it up with facts. Unfortunately, I think he hid some facts.

It’s painful to listen to the families in the series. What was it like for you to go on this journey with them?

Oldham: It was heart-wrenching.

Kenner: And gut-wrenching. I think these people ultimately grew to trust us and ultimately see us as perhaps helpful in getting more information and at least getting their cases reexamined.

Do you hope that that the series will bring about more interest from law enforcement to re-examine these cases?

Kenner: We absolutely hope for that. Just [recently] there were two cases that were re-opened through DNA.

Oldham: We see this series very much as the beginning, not the ending of anything. We really hope that what we’re doing is providing a platform and an inspiration for these cases to get re-examined and so the real work still has to be done.

Kenner: When we were pitching to Netflix, there were cases trickling in that were being solved. But it’s generally by accident. It’s not a concerted effort. It was always in isolation.

It seems like we are pretty sure that Henry killed three people: his mother, his teenaged girlfriend, Becky Powell, and 82-year-old Kate Rich. Did you walk away feeling like he probably killed more than that?Oldham: Who knows, maybe.

Kenner: Listen, Henry’s not a good guy. This is not a series about an innocent man. Henry had no impulse control and Henry was a screwed up character who did bad things. More to the point, there are potentially hundreds of people out there who are walking the streets free. It’s not that we’re out to say Henry didn’t kill people. But, by closing on Henry, or not investigating because of Henry, it allowed other people to get away with murder and for victim family members not to get justice.

Oldham: If you’re a police agent and you’ve determined that Lucas is guilty of the crime, then prove it. We’d love to get that DNA evidence. Just show us DNA evidence linking Lucas to the crime.

One of the wildest things of the series was the fake Becky. First, it was, wait Becky’s alive? Then, oh wait, it’s a fake Becky. Henry found himself a woman to pretend to be Becky. Unbelievable!

Oldham: Oh my God, it was amazing. It was amazing.

Kenner: That just goes to show what we’ve been saying. Here is [former district attorney] Vic Feazell, who wanted to prove Henry innocent. He believed it so much that he was ready to go all out and have Henry disprove people. Henry was a tricky character, so on some levels you have some sympathy for the Rangers because Henry is a very convincing character. The one difference is that Vic corrected his mistakes. He did have more definite proof. But the Rangers now have more definitive proof and they’re still not quite ready to accept or even ask for things to be open. I think there’s a desire to move on and not question, which is I think a mistake.