Predominantly set over the course of one sweltering July day in Chicago, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a fictionalized depiction of a heated recording-studio session that highlights the struggles and exploitative practices Black musicians have encountered. Adapted from August Wilson’s Tony-nominated play of the same name, it has racked up five Academy Award nominations, including nods for Viola Davis, Chadwick Boseman, and costume designer Ann Roth (who won for The English Patient in 1997). Davis’s makeup artist, Sergio Lopez-Rivera, was nominated alongside hair department head Mia Neal and Davis’s personal hairstylist, Jamika Wilson, the latter pairing making Oscar history as the first African Americans nominated in the Best Makeup and Hairstyling category. “It took a few days to come back down and absorb all the excitement of the nomination,” Wilson told Vulture in a recent Zoom conversation. “Especially because we’re the first African Americans [in this category]. It’s overwhelming with joy and then it’s such a responsibility.”

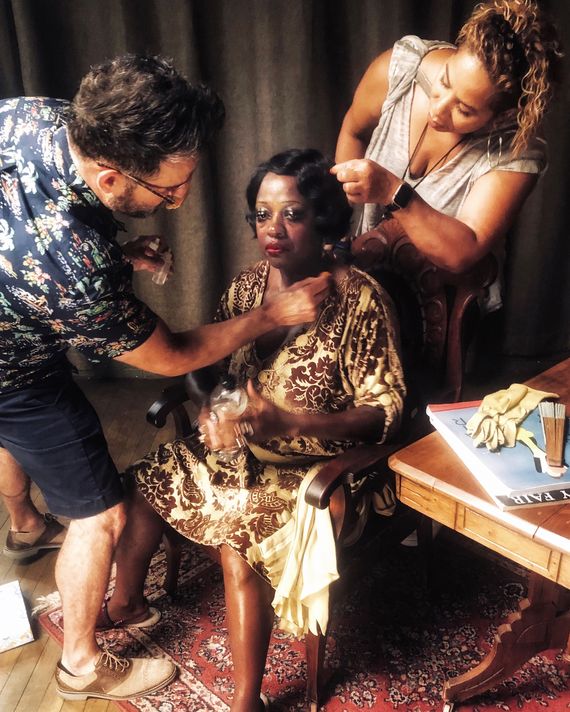

Wilson and Lopez-Rivera have both had long working relationships with Davis, and both are currently juggling Oscars press with prepping for Davis’s new role as Michelle Obama in Showtime’s forthcoming anthology drama The First Lady. Wilson first collaborated with the actress in 2008 during press for Doubt, and Lopez-Rivera began working with her on How to Get Away With Murder in 2014. Multiple makeup tutorials can be found online based on Davis’s master manipulator Annalise Keating in the Shonda Rhimes series, but the same is less likely for Ma Rainey’s greasepaint look. The role of the hair and makeup team isn’t simply to make an actor look glamorous, however, and Lopez-Rivera and Wilson are adept at using their expertise to transport Davis to another era. In Ma Rainey, her character’s performance plumage and warpaint are dialed down, but only a notch, as the Mother of the Blues enters the recording studio in a full painted face and custom wig, ready for whatever confrontations she may have.

In early April, Lopez-Rivera joined Wilson to discuss their work on Ma Rainey, the collaborative process with costume designer Roth, and how they brought to life a singer whose image had barely been caught on film. Here, they discuss their research and techniques, the ways Rainey used beauty tools as armor, and one similarity to a previous award-winning Davis role.

Limited Images

Each department undertook exhaustive visual research yet managed to uncover only a scant few images of Rainey, and out of the seven total, only one is a close-up of the singer. This shot proved invaluable to the creative teams. Inspiration requires a germ of an idea, and the singer’s headshot delivered the basis on which Lopez-Rivera could build a foundation. It wasn’t simply a case of mimicking the makeup, he notes, but understanding the psychology and the social factors behind Rainey’s choices. “Looking at this picture of her, I could get that she liked to be pretty and wear pretty things, indicated by this beautiful headband that she wore,” he says. “There’s a little, tiny sloping of her lower eyeliner that gave me the idea, Oh yeah, this woman is trying to make her eyes look more round.” His interpretation of this makeup technique was that Rainey “was intimately wanting to appear like the canons of beauty of that time.” Written descriptions from the period call out the blues singer’s lack of beauty — even going so far as to call her the ugliest woman in show business — but Lopez-Rivera explains that this didn’t negate her attempts to shine.

The metallic headband Davis wears is part of Rainey’s glitzy onstage glamour and is paired with a horsehair wig (more on that below). In collaborating with Roth, Wilson explains that they chose this particular headband because of its gold sparkle factor. While they had a specific vision of how Rainey would look in public-performance mode, her on-the-road and recording getup was a much more speculative process. “We had to imagine being her, pretty much,” says Wilson.

Continuity Challenges

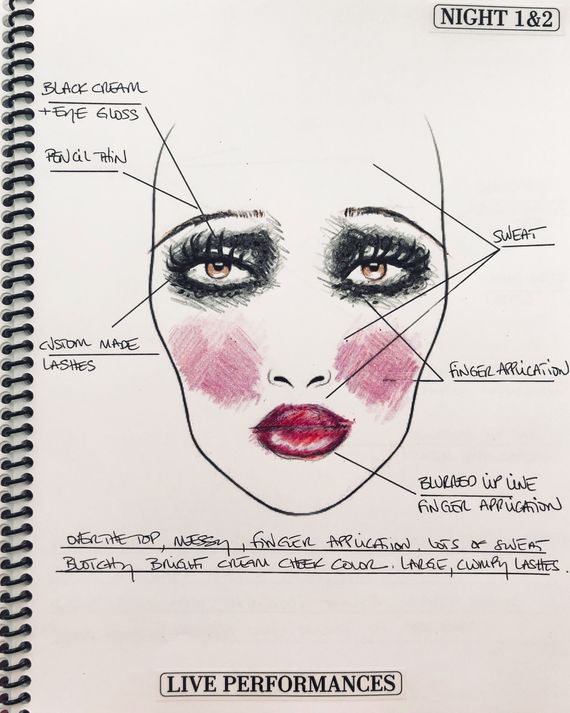

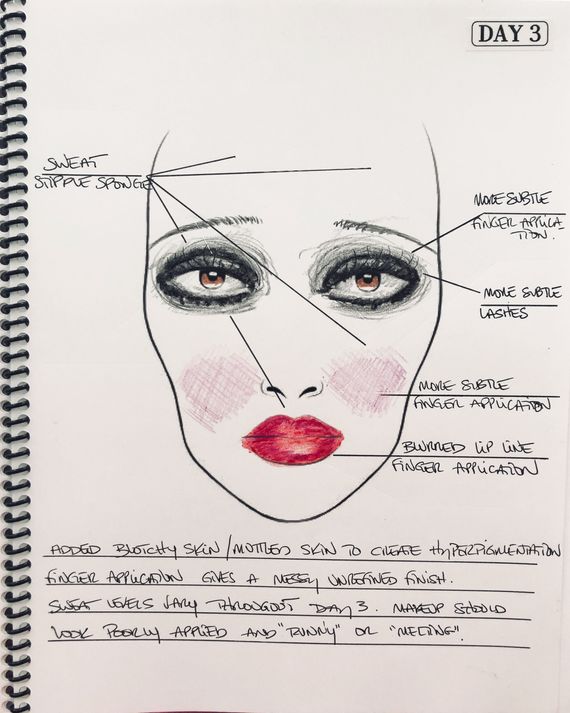

Conceiving the signature sweaty greasepaint look was only one part of the challenge for Lopez-Rivera as Davis’s personal makeup artist. “I was trying to come up with ways to make Viola less Viola and more Ma — because we didn’t go through the route of prosthetics, the challenges became very organic,” he says. Another concern the team had on the 40-day shoot — which primarily depicted one day — was maintaining tight consistency over the different stages of the shifting makeup. One of Wilson’s roles as Davis’s personal hairstylist was, she says, matching the evolving makeup work and “making sure I kept up with the continuity, dealing with Sergio’s sweat and all.” The combination of stifling heat and Rainey’s heavy garments produces a visceral image that, at times, looks as though her face is melting. Lopez-Rivera refers to the perspiration as “an incredible character in and of itself,” and the heat radiates off the screen and into our homes. “It was a lot of close-ups on Ma and focused in one room — we didn’t have a lot of different setups. You had no choice but to look right at Ma the whole time,” says Wilson.

Techniques and Products

“This story has to make sense with the fact this is a woman that learned how to do makeup when she was a teenager performing in vaudeville,” says Lopez-Rivera. “So automatically, there is a stage-makeup quality.” Likening this factor to an old movie star getting stuck in a style rut, he drew further inspiration from Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Yet there was an additional historical reality to consider, he says: “This woman in the 1920s didn’t have access to makeup the way white women did. How do you become creative? How do you do homemade products? Because if you have absolutely no access to foundation for dark skin, what do you do if you have hyperpigmentation?”

Fingertip application techniques helped him create the imperfections that would have been caused by both product unavailability and the heat rippling in every close-quartered scene. It was vital that the eyebrows were shaved before drawing them in using the pencil-thin style of the ’20s because it added to the authentic depiction. “Those choices didn’t come across as choices of mine but choices of Ma’s,” Lopez-Rivera says. “That’s why it couldn’t be perfect. It couldn’t be symmetrical.”

There’s a difference between making Davis’s cosmetic mask seem as if it’s slipping in the heat of a sweltering performance and the reality of having it fixed in perfectly melted place for the duration of a 14-hour shoot. “It’s like a life painting. It has to live, breathe, make sense with the temperature of the room or make sense with the struggle she’s experiencing at that moment in her day,” says Lopez-Rivera. Products by contemporary brands like RCMA, Blinc, M.A.C, and DM all helped paint the cosmetic canvas, but he did utilize techniques from the period, including layering on flaky, dry mascara. “For her show performances, her makeup was slightly more exaggerated, and she was more sweaty,” he says. When she removes her lashes at the end of a show, he wanted the effect of looking like “they have 50 coats of mascara.” Roth also considered the wear and tear caused by perspiration and the rigors of performing. “When Ma is finished at night, when she takes her clothes off, they’re wet. And they get on a bus or a train, and her clothes take a beating,” the designer said in a production note. “These clothes are tough; they’re not delicate. She would love them to be, but she’s not a delicate woman.”

Those Wigs!

A horsehair wig custom-made by hair department head Neal is a centerpiece of Rainey’s performing attire; the authentic material matches what the real singer wore. Neal imported the horsehair from England and not only had to build the wig herself to make it screen ready but also had to rid the material of inactive lice eggs and manure. And in order not to lose control of the bundle of hair, Neal had to build the wig before she cleaned it. The intricate process was further hampered by the hair’s thickness, which caused Neal to build the wig using a single-strand ventilation method. Each time she pulled a strand through, manure and lice eggs were scraped off. When the wig was completed, she boiled it and cleaned it (though its smell never went away). This proved invaluable beyond the obvious hygiene reasons. Wilson describes Neal discovering that horsehair softens during this process and likens the result to a modern-day synthetic wig. Neal would put it into boiling water to set the curl. “When she passed the wig along to me, we discovered that it really holds its curl,” says Wilson. “It also gives the feeling of kinky, textured hair. It was very bendable, so sometimes when there were touch-ups to do, you take your finger and roll the hair around your finger and set a curl there.”

A second wig, which Davis wears for the majority of the film, was European, its 1920s style created using rollers and a modern-day setting lotion for a wet, tight curl. “We pushed the waves back into the hair to set it with hair spray,” says Wilson. The team estimates that Davis would spend 90 minutes each day in hair and makeup. Lopez-Rivera calls the wig collection a “work of art.”

Erasing the 21st Century

Great teeth are often anachronistic, and losing Davis’s 21st-century smile changed everything for Lopez-Rivera. “I think they deserve an Oscar nomination all on their own because without them my job would have been so much harder,” he says of the gold-colored pop-in dentures Davis wore in the film. He credits the members of the hair and makeup team who are not listed as Oscar nominees with “such exhaustive work erasing traces of the 21st century from everyone in the background,” covering everything from tattoos and piercings to sideburns and hairlines. “It feels so authentic. It feels like you are almost watching a documentary,” he says.

Wilson recalls being in awe of Roth and how she prepped the background actors with specific backstories. “She would walk up to them and tell them their part — who they were and why they were in their wardrobe. It was amazing,” she says. Lopez-Rivera adds that the veteran designer explained the details, like “why that top button would not be buttoned on you, why you would not be wearing that lipstick because you’re coming from the market.”

Lopez-Rivera later discovered how members of other departments adjusted their work in reaction to the hair and makeup tests, including cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler, who “changed his lenses so that he could control the shine of the sweat without the color of her skin turning cool. Because he wanted the honey color but also really gritty.”

Sartorial Armor

“I definitely believe she knew her worth,” Wilson says of Rainey and the aesthetic choices she made. The costumes, makeup, and hair in the film reflect the singer’s sartorial armor. Lopez-Rivera cites the extensive research each department undertook to create a fully formed figure as the reason it all works so beautifully. “You realize that this woman struggled with making the world see her, with making the world give her value,” he says. When Rainey is on her way to the studio, we see her openly flaunting her wealth through every material good possible, including a new car and luxurious garments. Wearing a fur collar or velvet gown in the middle of a Chicago summer makes a statement, and the makeup artist observes that she was “like a walking billboard of everything she owns.”

“Ann will tell us there’s no jewelry left in the hotel; everything is on her hands. Anything she owns is on this woman’s body,” he says. “It’s interesting, psychologically speaking, that visually it was important for her to have people look at her and know that she was worth it.” Wilson agrees that the world was against Rainey, and Lopez-Rivera adds, “I think she thought — rightly so — that by announcing her worth ahead of time, she would minimize the confrontations that she would encounter otherwise as a Black woman in America. That it somehow would protect her a little bit.”

Lack of Vanity

In 2014, Davis delivered a memorable performance in an early How to Get Away With Murder episode that is indicative of her ability to eschew vanity. A transformative scene in which she slowly removes her makeup and wig lays bare a hardened and polished character. (It also features the unforgettable cliffhanger line “Why is your penis on a dead girl’s phone?”) On HTGAWM, it was Davis who suggested this “unmasking,” and Lopez-Rivera likens this moment they worked on together to Davis’s attitude on Ma Rainey. “The reason why she was able to do that scene is the same reason why we were able to do this movie. She does not care about her own vanity when she’s performing,” he says. “Even when offered the opportunity, like, ‘Hey, we can film this scene in a way where we can cut away from it, and we don’t have to keep rolling so you don’t actually have to take your makeup off,’ she was like, ‘Absolutely not! I want to do this.’ She’s interested in authenticity. She leaves her vanity at home.”

From Ma Rainey to Michelle Obama

Awards season 2021 has seen glam squads step up the beauty game for remote broadcasts. Wilson has been multitasking between working with Davis on creating exciting looks for multiple magazine covers and virtual red carpets as well as doing her own press and running a salon business. “I’m really a behind-the-scenes person, so doing interviews is totally out of the box for me,” she explains. Wilson and Lopez-Rivera have been juggling Ma Rainey press and prepping Davis’s next project; they’ll soon fly to Atlanta for Showtime’s The First Lady just days after the in-person Oscar ceremony. Wilson says she’s busy creating wigs for the show, an anthology drama focusing on Eleanor Roosevelt, Betty Ford, and Michelle Obama in its first season.

Lopez-Rivera says his preparation for The First Lady consists of some very granular but extremely important glam work. “I am about to start designing the different shapes of eyebrows of Michelle throughout the years,” he says, showing Vulture a mold of Davis’s forehead and nose bridge. Using transfers and stencils, he will match the continuity to Obama’s changing brows. After doing this whole awards season from behind a screen, Wilson and Lopez-Rivera are looking forward to the Oscar ceremony (and both have their outfits picked out). “I can’t wait to be with everybody together, all the nominees — by now we would know each other so well in a normal, non-pandemic year,” Lopez-Rivera says enthusiastically. “Like, come on, let’s hang out!”