After Hours is a one-crazy-night movie about how work sucks. We don’t need to know much about Paul Hackett, the data-entry drudge played by Griffin Dunne, beyond the fact that he is bored with his job and the life it has afforded him. Dining alone at a café after leaving his nondescript Manhattan office, he meets the cool, chic Marcy (Rosanna Arquette). When he winds up at her apartment, ostensibly to buy a plaster paperweight from Marcy’s sculptor roommate (Linda Fiorentino), a series of unfortunate events leaves him stranded downtown, where he meets a sensitive waitress (Teri Garr), an erratic bartender (John Heard), a Mister Softee truck driver (Catherine O’Hara) convinced he’s a burglar, and another sculptor (Verna Bloom), who glues him into one of her creations to hide him from an imposing mob. Paul is like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, leaving home (the Upper East Side) and stepping into the confusing world of Kansas (Soho).

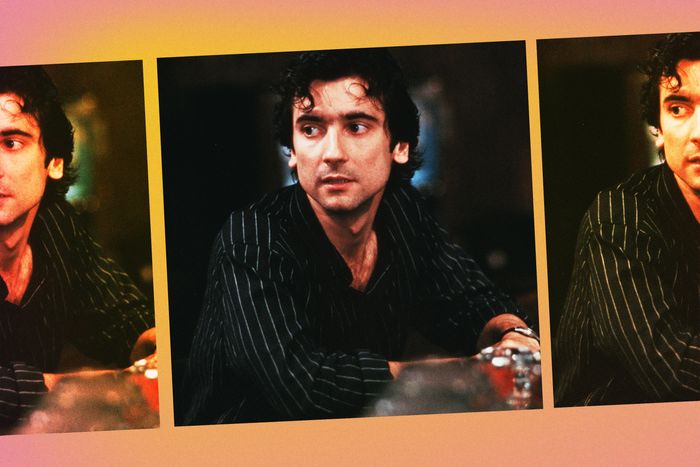

Martin Scorsese’s screwball noir is beloved today, but it basically flopped back in 1985. He made it while his longtime passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ, was temporarily stalled, which might as well be Scorsese’s own personal “work sucks” story. Maybe that backstage drama enhanced the paranoia at After Hours’s core, though by Dunne’s account, the production was a blast. He got to dash around New York with a bunch of funny co-stars and carry a film that would go on to enjoy a major renaissance. Dunne, 66, called up Vulture to reminisce about the experience, including Scorsese’s mandate that he abstain from sex during the shoot and why the movie almost ended with Paul stuck in that sculpture.

Are there even any questions left that you haven’t already been asked about After Hours at this point?

Give it a shot. I’ve certainly been asked a lot. It’s sort of one of those movies — I’ve done three of them — where the interest has quadrupled and continues to. It’s true with After Hours; it’s true with An American Werewolf in London; and with a movie I directed called Practical Magic. They were greeted with “yeah, okay,” and then the audience interest has increased with every generation.

Do you have any theories as to why After Hours had a resurgence?

Certainly the internet, which is able to turn lots of people on to a movie they hadn’t heard of in microseconds. And the easy accessibility of movies. If you hear about a movie, you can see it five minutes later. There’s immediate gratification. But I think the increasing popularity of the movie is that it resonates with a certain paranoia that we’re all familiar with. The idea of saying the wrong thing, doing the wrong thing. Being persecuted and chased through the streets of Soho is a pretty good metaphor for how easy it is to trip up. It’s what everyone fears: to be an outcast and chased by the mob on the internet. And the movie is done, obviously, in a really funny way. I think people appreciate the persecution humor of it.

Tim Burton was originally going to direct After Hours. Were you involved at that stage?

The origins of the script came about the very first year the Sundance labs were happening. There was a great Serbian director named Dušan Makavejev. He was teaching at Columbia, and he had an assistant at the time named Joe Minion, who wrote this script as a thesis. He gave it to producer Amy Robinson, and Amy said, “Oh boy, I read this amazing script by this student.” She sent it to me, and we went to see a movie that had an incredibly inventive short by Tim Burton before it. He had yet to make a feature film. We went to Disney, where he was an animator, and met him. He had the short-sleeve shirt and the packet of pens in his pocket that were bleeding into the shirt. You can tell this guy was insanely gifted.

But before then, the first very person we gave it to was Marty. He was just starting Last Temptation of Christ. We hadn’t gotten too far with Tim, but Last Temptation was shut down. It was the one that was going to be with Aidan Quinn. On the flight back from Casablanca, After Hours was at the top of Marty’s reading pile for “What am I going to do next?” And he said, “It’s really great. I’d love to do it.” So we said to Tim, “Wow, a crazy thing happened.” We didn’t even get very far into the conversation and he cut us off and said, “If Mr. Scorsese wants to do this movie, I’m not going to do anything to stand in the way. I gratefully withdraw.”

Tim Burton is a big name now, but as you said, he wasn’t well known yet, unlike Scorsese, who had made Taxi Driver and Raging Bull by that point. What did it mean to you for Scorsese to step in and direct the film?

Well, in fact, they were both out-of-the-box ideas. For Marty, people didn’t know how funny he was. He did King of Comedy and was duly punished — another movie that has since found a whole new audience that realizes how incredible it is.

Yes, I think that movie was misunderstood at the time.

Mm-hmm, and so he was a little bit in director jail at the time. We just knew visually Tim was a genius. What he would do with the sculptures and the creepiness of Soho — the desolation of it and the things around the corner that you can’t see — would also be funny, but obviously a very different movie.

I wonder what he would have done with some of the production design. I almost don’t think you need to elevate Soho in the German Expressionist way that Burton does with his scenery. It’s already a hellish adventure without any sort of exaggerated aspect.

Absolutely. All that was required was Marty and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus’s incredible tracking shots, and the fear and the humor would be there.

Is it true that Scorsese asked you to refrain from sex and sleep during the shoot?

I’m afraid it is, yes.

How did that go for you?

It went well until one day came along. I started to do the next scene with Linda Fiorentino where she’s getting massaged, and I was just too goddamn relaxed. Suddenly I was kind of a cool guy, and Marty went, “Cut! Let me talk to you. You got laid, didn’t you?” He was really pissed. He said, “You fucked up that whole thing. We’re going to do it again.” And anyway, the energy was back.

He made you paranoid like Paul.

Exactly.

And did you deprive yourself of sleep?

No, some gaffers came to my apartment and blacked out all my windows so I would arrive at my place as the sun was coming up and sleep all day. I kind of got into the groove of it. It took longer to get out of it than to get into it.

That early scene in the taxi, where you’re speeding downtown and the $20 bill flies out the window — was that actually shot on the streets of New York?

Yeah, and the guy who was assigned to us from the New York Police Department got into a little bit of trouble. We were following him — it was a quiet street, Second Avenue — and he just floored it. So did the driver, Larry Block; he floored it. I think we hit like 80 miles an hour, so I was really flying around back there. The cop got in trouble for letting us go that fast.

What was it like to dash around Soho in a rainstorm?

The rain was manufactured, but I was really wet. It was torrential rain. It was a lot of Singin’ in the Rain, just splashing in these huge puddles. And it lasted all night. But I never had so much fun in my life.

How much papier-mâché ended up on your body?

It took quite a bit to get off at the end of the night. I would just soak in a tub and get all of that papier-mâché off. They really stuck me in that sculpture, and Cheech and Chong carried me around. It was pretty easy to look claustrophobic in it with just my eyes.

The movie was originally going to end with you remaining in the sculpture, but test audiences didn’t like that fatalistic outcome, right?

Yeah, it was too claustrophobic. It didn’t give them any release. They worried about the boy in the sculpture: Is he ever going to get out? Marty showed it to his friends Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg. We just came up with ideas. I forget whose idea it was that we got so excited about, which was that in the basement, Verna Bloom would go, Come here, quick, hide! She’d point to herself and then it would be a quick cut to her being pregnant with me. I think she was going to give birth on the West Side Highway and I was going to come out covered in plasma. And David Geffen, who financed the movie, went, No way, that is a disgusting ending.

I can’t say that I disagree with him based on that description.

No, I know! We were desperate for an ending, and it seemed like a good idea at the time. He brought us to our senses, and then we came up with Paul flying out of the back of the van and he cracks open and off he goes to work.

How long did it take for them to glue you into that sculpture?

It was in two pieces, and I fit into it in an embryonic kind of way. Getting into it was not a big problem; it just took a while to seal me in. I would be in that thing for quite some time before we rolled, and I wasn’t getting out between takes.

There’s a scene in After Hours that means a lot to a lot of people, which is the two leather guys making out at the bar. No one comments on it. It was very nonchalant at a time when you really did not see that in media. Was that detail in the script?

It was basically just a line in the script. I was there for all the auditions with all the actors, and we would bring in groups of men in chaps and handlebar mustaches. We’d bring them in two by two and say, “Start making out.” And Marty and I would watch them make out and go, Yeah, that’s pretty good. What’s the next one going to do?

That’s a fun audition day to be part of.

That was a fun audition, yes. There were, like, 30 candidates or something.

Were you also part of the auditions with the various women?

I read with all of them. It was great.

I’d say Teri Garr was the most famous of the ones you ended up casting. She was a pretty good get. How did you land on Teri as Miss Beehive?

She’s an old friend of mine. Marty knew that’s who we wanted and he really agreed, so she was grandfathered in. She was always going to play that part. Rosanna Arquette didn’t audition. Marty always wanted her. By then, I’d already done three things with Rosanna — I produced the movie Baby It’s You, and we’d been in Poland shooting a TV movie on the John Hershey novel The Wall. When Marty was in the desert in Morocco, he and screenwriter Jay Cox were sitting around a fire. He was scouting for Last Temptation, and as the fire is going, they’re looking up at the stars and they both started to sing “Rosanna in the highest,” because they both loved her. And so one of the first things out of Marty’s mouth was how much he’d like her to play that part.

The streets of Soho are totally dead throughout the movie. Were they shut down?

Yeah, you didn’t have to do much shutting down because they were already pretty dead. The people in the lofts around us were up just like we were. There were artists painting. The only time we ran into a problem with the neighborhood was when I dropped to my knees and screamed to the heavens, “What do you want from me? I’m only a word processor!” We did several takes of me screaming at the top of my lungs. It must have been 4 in the morning, and a woman lifts up her window. She has a cigarette in her mouth, takes it out, and screams, “Shut the fuck up! Just shut the fuck up!” And Marty looks up at her and says, “Tell that woman to put out her cigarette.”

Did Scorsese ask you to have a unibrow in the movie?

Well, he didn’t tell me to get rid of it. I forgot that I had a unibrow. But yes, I got the Frida Kahlo look from my mother, who did get rid of her unibrow. She’s half Mexican, and I don’t know why I got it too.

So you just happened to have it at that time?

I just happened to have it. Nobody ever said, “Get rid of it.” I wasn’t even aware of it, but you’re right. Now there’s the first question I’ve never been asked. I’m looking in the mirror now, and I don’t have one. I don’t know what happened to it.

Yes, I was looking at photos from your most recent roles to see if you still have it. But I’m not critiquing the unibrow! How aware are you of the theory that Paul is dead the whole time and this is an endless loop of the cycle that he experiences in hell?

I’m not, but I would bet when The Sixth Sense came out, that probably kicked in. Our references were always based on Kafka or The Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland — going-down-a-rabbit-hole things. But it’s always fun to make a movie that people bring their own theories to. We didn’t think of it.

Did you have a wrap party?

We had two. We had an impulsive one when we wrapped the last day of shooting. We did the crane shot of dropping the keys. I remember Robbie Robertson being on the set that day. And then we all went to Bob Colesberry’s loft, our co-producer on this, which was in Marty’s same building. We partied all day.

Right, because you had finished shooting at night.

Yes. And then we had the official wrap party the next night, and everybody was burned out from staying up all day.

I’m hardly the first person to say how surprising it is that this movie didn’t make more money. To the best of your recollection, what were the expectations around it when it was opening?

When we changed the ending, the test screenings were enormously successful, so we had very, very high expectations and were surprised and confused it didn’t do breakaway business. It wasn’t even No. 1 that weekend. Yet in New York there were lines around the block for weeks. I don’t think it resonated much with the rest of the country. But it’s become a sort of genre unto itself. After Hours has become an adjective for a certain kind of movie since then. I was not unfamiliar with this because Werewolf was the same thing. It was, Why do they have humor in horror? Pick one. And now, since Ghostbusters, that’s de rigueur — you’ve gotta have a couple big laughs between all the killings. I think it was, as they say, a little ahead of its time.

Is there an anecdote that stands out that you haven’t gotten to tell about After Hours?

Yeah, the mood of that movie and my personal life manifested one night. A couple weeks before shooting, I had gone to Sri Lanka and I met a German girl. We traveled around a bit, and she said, “I’m coming through New York to go to Ohio to be an au pair. Can I stay with you for the night?” I said yes. This was some weeks before we started shooting. Then she went to Ohio, and in the middle of shooting, she wrote me desperate letters and called and said, “This is a disaster. Can I come and stay with you until I figure out what I’m doing?” I said, “No, I’m in the middle of shooting and I’m in a tiny apartment. You can’t.” She was very upset and I was very guilty, but I couldn’t do it. We were about six weeks into shooting. She said, “I’m coming to New York. I’m gonna figure it out.” Then I never heard from her. I got letters in German from her parents going, Have you seen her? Then late one night, we’re shooting on Spring Street and I see this filthy homeless girl who looked like my German. I went, Oh my God. And I leaned down: “Greta! Greta, I’m sorry. Are you okay?” She looks up and we have eye contact and I realize it’s not Greta at all. She attacks me and scratches my face and has to be pulled away. Craft services pulled her off me and gave her a few sandwiches. The happy ending to this is, thanks to Instagram, just last year I got a DM from Greta going, Do you remember me? We were in Sri Lanka together. I went, Oh my God, you’re alive!

More reasons to love new york

- We Took New York’s TikTokers to Lunch

- The Three Frank Jrs. in Merrily We Roll Along Will Sign Your Playbill

- New Yorkers Live Side-by-Side and Worlds Apart