I met Sam Gilliam, who died this week, just a few years after he became the first Black artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1972. I was an artist myself back then. We were at a residency called Ox-Bow, on Lake Michigan. I believe it was the first time I had been away from Chicago for more than a week since I’d been born. I was terrified. But I was open to new experiences in this haven away from the chaos of my family, in the luxuriance of nature and sand dunes. I did not know how lucky I was until I met Sam.

I was in awe of him.

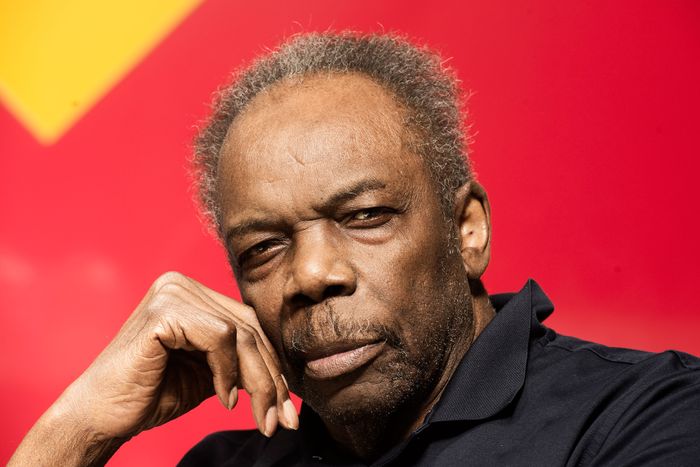

He was one of the most famous artists I had ever met. He was tall, had a tremendous laugh and charisma that made me want to be like him. He seemed to be brooding out loud but in a way that let you in on his thoughts and feelings. He was rhapsodic in his responses to the world and the people around him. I felt like he existed on an artistic astral plane.

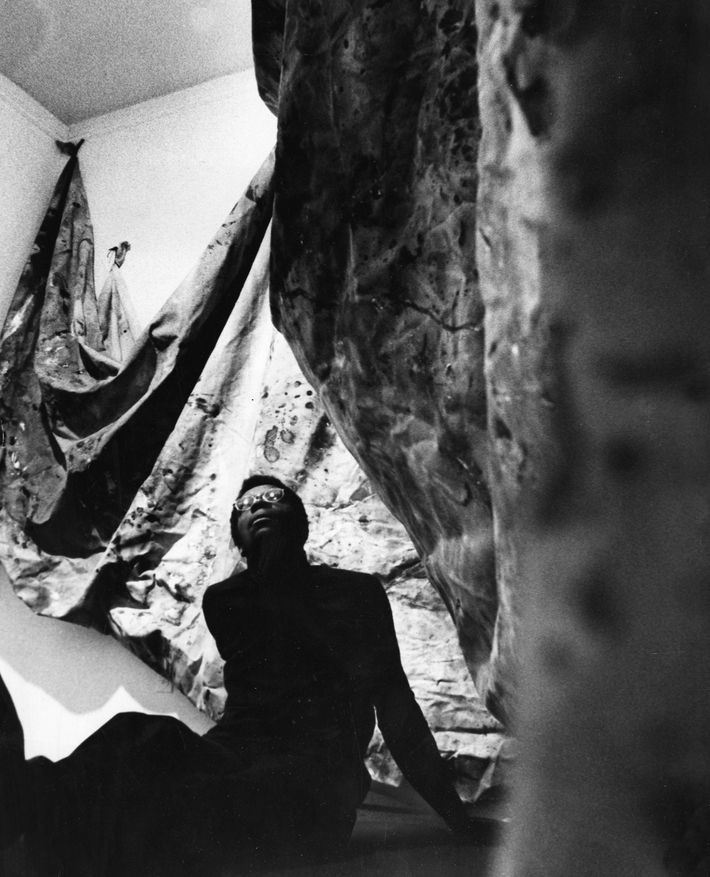

His huge Technicolor paintings, draped without frames, crossed over into sculpture — tabernacles to fearlessness and radicality. Hung from the ceilings or tacked to the walls, they looked like canvas mountain ranges or gigantic tents and huts, marching cities on the plain.

The epic scale of these paintings intensified the minds of viewers. They felt fun, thrilling, revolutionary — an advanced vocabulary of familiar things acting strangely. Here were paintings that were storm-blown into swooping, cresting shapes, great oceanic structures that were metaphors for the sublime. You could not turn away.

By his 30s, Gilliam had already cracked the code of the canon. He took color-field and stain painting, Ab Ex all-over-ness, and cross-wired it with the shaped paintings of the early 1960s, which bent and broke through the traditional rectangular frame. He took the lower tones of the more serious monochrome paintings of the previous half-century and infused them with the spirit of the exploding pluralism of the 1970s, which saw artists probe the outer banks of the painterly solar system, where things took on new forms.

I’d never felt the past, the present, and the future congeal quite this way. He was a Frankenstein undoing the death of art and recombining its body with what he told me were his ideas of “African art and textile.” The effect was like poetry, sedentary sails singing duets in space, abstract gardens hovering in air. These were paintings that were at once dancing spirits, opulent peacocks, ornate tableaus, and celestial gathering ghosts.

The two of us stayed up very late every night and talked about life and women and art. This was one of my great sentimental educations. We also bonded because we both knew the late, overlooked painter Emilio Cruz, who had been my role model through the early 1970s and took me to tiny jazz and blues clubs in Chicago. Gilliam and I remained close all that summer. I stayed; he left. And that was that.

What happened next is a story far too common. As important as he was, Gilliam became less visible. I lost track of his work altogether. By the time I moved to New York a few years later, I did not even know how to contact him. (For most of his life, he remained based in Washington, D.C.) Art-world apartheid was that surgical and hellish. Excised from the timeline was a great artist who kept making great art. We will never know how often this story was repeated.

Fate changed for Gilliam. The art world was lucky that the Corcoran Gallery in D.C., the David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, and a number of curators began showing Gilliam’s work again around the turn of the century. His orbit turned out to be as strong as it was when I first met him.