The first time Fall Out Boy headlined the Chicago rock club Metro could’ve been the last. The gig was a substantial step for a band that, until then, had been a bare-bones project: top billing at the venue where they’d seen their heroes. “That was the biggest show we could imagine playing,” says Patrick Stump, the band’s singer and guitarist. “This is your one shot.” It was February 2003; they’d just solidified Fall Out Boy’s lineup (of Stump, bassist and lyricist Pete Wentz, guitarist Joe Trohman, and drummer Andy Hurley) after a little over a year and were preparing to prototype emo-pop with their debut, Take This to Your Grave, in a few months. (That night, they played the standout anthem “Grand Theft Autumn/Where Is Your Boy” for the first time.) Stump and Wentz wanted to take time off from school for the band — even though Wentz was just shy of graduating with a political science degree — and hoped seeing such an important show would convince their families to allow it. When Fall Out Boy made their Metro debut in 2002, they’d opened a four-band bill for $75 — which helped cover the cost of a paper cutter to make flyers for the event. This time would have to be different. “We were like, ‘How do we get some production?’” says Wentz, also the band’s unofficial creative director. “And we couldn’t really afford anything.” But bach party props? Those come cheap. “So we had these giant inflatables,” Wentz continues, “and they were penis-shaped.”

Taller than the whole (famously short) band, in fact. When they threw the balloons into the crowd that night, some made their way up to the balcony where their families were sitting. One reached Wentz’s mom; another whacked Stump’s grandmother. “This is actually insane,” Wentz remembers thinking. “After that, it was the first time my parents were like, ‘Well, maybe you should just take a year off from college and do that.’”

A generation ago, Wentz and Stump would be among those crammed onto the Metro floor, there to see Chicago punk progenitors Smoking Popes or future tourmates Weezer. (One reason to love Metro: It books all-ages shows.) It’s a local mainstay, equal parts historic theater and dingy club with one-sink bathrooms that’s hosted everyone from R.E.M. to Chance the Rapper. Stump thought of Metro as “a place that very serious artists played” — after all, his dad had seen Bob Dylan there in 1997 — until he happened upon a 1999 set by Texas post-hardcore band At the Drive- In. “They played like it was a basement show, just thrashing off of walls,” he says. “It blew my mind that you could do that at Metro.”

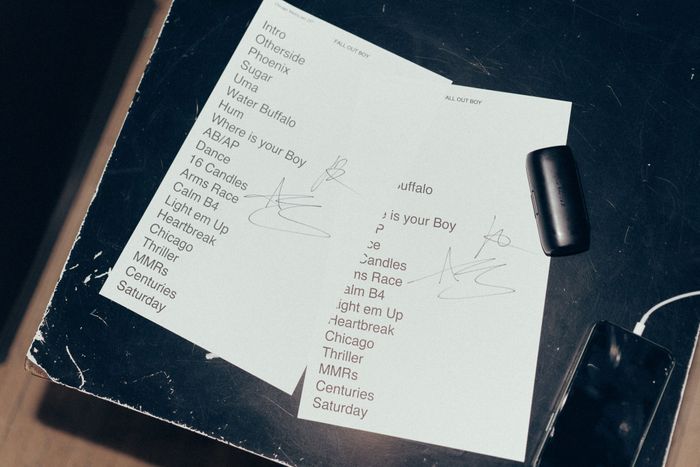

Some months after the dick-shaped balloon incident, they returned for a Take This to Your Grave release party; by December 2004, shortly before their Island Records debut, they were already too popular to be playing a 1,100-capacity venue, selling out the place — but kept doing it anyway. In January, that long-standing affection brought the band back to the scene of their earliest prank-crimes, nearly two decades later, for the first concert for their upcoming eighth album, So Much (for) Stardust.

At sound check, the songs from Stardust come easy to them and command the room, especially Hurley’s booming drums and the tracked, cinematic piano of lead single “Love From the Other Side.” It’s the old songs that give the band trouble — “I’m too old for this shit!” Hurley yells after a take of 2003’s “Calm Before the Storm,” which Stump fumbles the lyrics to. But Stardust has echoes of the band’s roots: It’s their return to Fueled by Ramen, the well-curated, tastemaking emo and pop-punk label that released their debut album, Take This to Your Grave, but which they departed for Island Records for the follow-up, From Under the Cork Tree. With hits like “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” and “Dance, Dance,” that record turned Fall Out Boy from DIY upstarts to emo-punk heroes. And 2007’s Infinity on High only increased their stardom. Their songs didn’t betray their basement-show roots, with throttling guitars and Wentz’s screams, but they also had the big, easy-to-sing-along choruses that would become standard in pop-punk. Along with acts like Avril Lavigne and Paramore, they filled a gap in Top 40 rock as the post-grunge era faded. But unlike peers who were more dedicated to the emo crowd, like My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy also actively chased the mainstream, playing “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” on TRL and with Rihanna at the VMAs; Beyoncé and Jay-Z once attended a show at Roseland Ballroom, and a pre–Keeping Up Kim Kardashian starred in the music video for “Thnks fr th Mmrs.”

Folie à Deux began the band’s experimental streak, bringing soul and power-pop into their music, but sold considerably less than their previous albums.They took a hiatus in late 2009, and when they returned in 2013, pop-punk bands were beginning to be replaced by a budding generation of emo rappers. Wentz noticed this more genre-bending music landscape and felt like they would have to lean further into pop to “survive” as a rock band — or maybe, more accurately, return to their mid-’00s level of fame, which is a few steps past survival. Beginning with Save Rock and Roll, the band’s post-hiatus albums featured synthesizers, pop producers, and even song placements on ESPN and Disney’s Big Hero 6. But to Wentz, who often speaks in pop-culture references (and has been watching The Last of Us), making more pop-oriented music felt like reaching quarantine in a zombie apocalypse. “We figured out how to exist somehow, but we’re like, mmm, kind of existing.” The band still had an appetite to do more, like on 2018’s Mania, a heavily programmed, hip-hop–influenced album that some fans feel veered too far into pop, but it gave the band a chance to flex new creative muscles. “It was me goofing around with what you could do to mangle sound waves,” Stump says. “And that was really fun, but we did that, so I didn’t want to just go back and do it again.”

FBR’s vice-president of A&R, Johnny Minardi, had been pestering the band about new music, and whether the band wanted to release it on his label, since their contract with Island ended in 2018. Returning made sense, after Wentz and Stump worked closely with FBR for years on the duo’s indie label DCD2 (formerly Decaydance). The band also wanted to bring longtime producer Neal Avron back into the fold, a much more difficult negotiation. After helping craft the band’s 2000s dominance with Cork Tree, Infinity on High, and Folie à Deux, Avron became an in-demand, Grammy-winning producer for musical-theater soundtracks.

If Fall Out Boy wished to make a return to 2000s form, now’s the time to strike. The sound they helped define is a hot commodity once more, with a wave of pop-punk nostalgia cresting early into the new decade. TikTok stars have pinned their crossover hopes on pop-punk, and their favorite producer, Blink-182’s Travis Barker, is now married to a (different) Kardashian. Even Olivia Rodrigo got a pop-punk song to No. 1, with “good 4 u.” In this era, Fall Out Boy’s classics have only grown more beloved, so much that Cardi B went viral for singing “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” to ring in 2023. But for Stardust, nobody involved wanted a return to Avron to mean a return to that classic sound. Stump knew Avron would be the meticulous, patient producer who could bridge the past decade of pop with the heavier rock music they wanted to make again, and sold both the band and Avron on that vision. Wentz soon saw Stardust as a chance to give up worrying about where they fell between pop and rock. “There’s kids that got into this band because of Big Hero 6, and then there’s kids that got into it because we played on Warped Tour,” he says. “How do we mix those two things together in a way that doesn’t feel patronizing and is organic and artistic and very modern? That’s the attempt, at least, with this record.”

The band hasn’t abandoned pop touches on Stardust; they’re just using them more intentionally — a piano loop here, a synth track there. But more notably, Stardust has some of the band’s most unabashed rock music in at least a decade. Lead single “Love From the Other Side,” which reflects on the restlessness of the pandemic and fame, is one of the loudest songs in the band’s entire catalog. They weren’t confident about leading off with it until they held a listening session with the interns at Warner Music Group, Fueled by Ramen’s parent label. “Nearly every hand went up,” Stump remembers. “It knocked me back like, Oh, you have to listen to that.” It worked, becoming the first No. 1 on the alternative charts of their career.

Lead guitarist Joe Trohman was integral to this new direction — he called Stardust “the guitar-heavier album I had been fighting for us to make for almost a decade” in his 2022 memoir, None of This Rocks. But the same day Fall Out Boy released “Other Side,” Trohman announced in a note to fans that he would be taking a temporary break from the band for his mental health. “I appreciated that he was public on that level with it,” says Wentz, who has been open about a previous suicide attempt. “We’re a generation and a half away from Leave It to Beaver, where you’re just like, ‘Everything’s normal.’” Trohman is, however, still in the band. “I was really frustrated at first when people would ask me about it and imply that he wasn’t there,” Stump says. “I’m like, ‘No, no, no. He’s exactly as much a part of it as any of us.’”

Wentz had been thinking about the sustainability of the band as much as Trohman; it shows on Stardust. The title track, which closes the album, candidly addresses the expense of fame: “I need the sound of crowds or I can’t fall asleep at night.” In the catchy, carnival-jingle bridge of “Flu Game,” Stump cries, “Someday every candle’s gotta run out of wax / Someday no one will remember me when they look back.” Then, on the next line, the band finds a semi-solution: “Can’t stop, can’t stop till we catch all your ears though.” Wentz is clear the end of the band isn’t on the horizon, even as early peers like Panic! At the Disco hang it up. (After all, Paramore just released a well-charting new album, and My Chemical Romance is wrapping up a highly successful reunion tour.) But more than ever, he wants to make sure they have no regrets. “We approach everything, I think, like, We are giving it our absolute all. We’re not planning on going to overtime,” he says.

When Fall Out Boy arrived at Metro for sound check that afternoon, there were already dozens of fans lined up on the sidewalk, braving the wet winter slush for their 46th, 31st, 24th, or even first Fall Out Boy show. Wentz knew what they were looking for. “I think people often have nostalgic FOMO, where you’re like, Wow, I wasn’t old enough or I didn’t live in the right city,” he says. And as much as they wanted to push forward, the band was looking for a taste of the past too: Would playing “Other Side” in their old favorite venue feel the same as some of their earliest songs? It did. “If you were like, What did it feel like then? This is what it felt like,” Wentz says a few days after the show. “It felt exactly like this.”